From Patients to Prisoners: A Modern History of Mt. McGregor - Part One

Aerial photograph of the Metropolitan Sanatorium on Mount McGregor, New York ca. 1921

““Mount McGregor is as near Heaven as it is possible to get on this earth.””

View of Mt. McGregor from the valley. Source: Philip Kamrass/ Times Union (2011)

When one travels in the valley east of Mount McGregor, New York their eyes can be easily drawn to a bunch of buildings perched on the ridge above. For many who are unfamiliar, this sparks a curiosity to understand why a large facility would be built in such a place and what it may have been used for. The tale is worthy of being told as the mountain touched the lives of so many in the 20th and 21st centuries. From patients seeking health, to war-weary veterans looking for recuperation, to persons with intellectual disabilities, and incarcerated individuals, the mountain community has changed dramatically in the last 125 years. The mountain’s effect on thousands of residents and visitors has had a ripple effect extending well beyond the local area. There’s one thread that weaves through it all, and that is the undeniable charm and attachment to the natural beauty and peacefulness of the place that affected almost all who came to the place. It presented all who came with an opportunity to seek some form of wellness in the place itself. Even though the mountain has been largely dormant for the last decade, this series of articles on the modern history of Mt. McGregor, through historical images and personal stories, is meant to provide a compelling glimpse into the past. One can better envision the different eras of the mountain’s history as they drive up it on their journey to the thriving Grant Cottage State Historic Site next door, fostering a better appreciation for the mountain and the many whose lives it transformed. (Important Note: The Mt. McGregor facility property is owned by the New York State Department of Corrections and patrolled by the New York State Police. It is not open to the public).

1903 Advertisement from The Daily Saratogian

As the 20th century dawned a new chapter in the history of Mt. McGregor also dawned. In the years after the resort era ended there was speculation as to the future of the mountain. Vestiges of the once opulent Victorian resort were still present in 1903 when the land was offered up for sale. The public maintained a keen interest in seeing the revered historic cottage where Ulysses S. Grant died protected. The land surrounding the cottage was purchased by individuals with intentions that alarmed the preservation and conservation-minded public as their prime concern was lumber. The threat of deforestation loomed over the mountain prompting a call for it to be purchased and transferred to the state to be protected as a state reservation (now known as a state park). Just as this was being discussed a party stepped into the picture that would dramatically transform the mountain’s identity for the next three decades.

Cover image for a 1921 educational booklet on tuberculosis published by MetLife featuring the double red cross symbol of the National Tuberculosis Association. Source

The Metropolitan Life Insurance Company (MetLife), founded in 1868, was the largest life insurance provider in the United States by 1909. In that year the company completed the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company Building in New York City which held the status as the world’s tallest building for a few years. One of the biggest risks facing their enormous workforce and the public in general was the infectious disease tuberculosis (TB). TB went by multiple names throughout human history such as phthisis, the White Plague, and consumption. Regardless of what it’s called, it has remained one of the deadliest diseases in the world into modern times. It is a devastating disease that can cause an untreated sufferer to waste away over a long period. Responsible for the death of one in seven Americans in the 19th century, significant scientific advancements and discoveries offered hope for effective treatments and potentially a cure as the 20th century began. One of the options that emerged in the United States in the late 19th century was the sanatorium treatment which consisted mainly of a regimen of solid nutrition and rest at a dedicated facility. These facilities were typically built in pristine natural environments believed to be optimum for recuperation. Increased public health initiatives and education were starting to reduce the prevalence compared to the previous century, but the disease remained a significant health risk. In the 20 years after Dr. Edward Livingston Trudeau established a TB sanatorium in Saranac Lake, NY, the number of similar facilities had grown to over 100 nationwide. When it was suggested by leading TB physician Dr. Sigard A. Knopf that MetLife “should build a sanatorium for its employees who had tuberculosis and for the advancement of scientific investigation” the company decided to move forward with the plan.

The company first investigated a rural location just north of New York City in Westchester County, but faced “local feeling against it”, due in large part to public fear of the disease. The company next set its sights on Mount McGregor in Saratoga County in 1910. The isolated and wooded location at 1000ft of elevation on the eastern slope of a ridge with a water supply offered a very scenic and suitable location for a new sanatorium. The company overcame its first obstacle by achieving successful approval from state and local health officials over the protests of local residents. Much of the concern came from residents of the nearby resort town of Saratoga Springs, with concerns ranging from contamination of water to “changing the character of the summer visitors.” One of the initial missions of the company became educating the local residents in order to “drive from people’s minds the fear which is based on ignorance.” Oliver Clarke, a Civil War veteran who had survived the horrors of Andersonville prison camp, and had been resident caretaker for Grant Cottage on Mt. McGregor for 25 years, came out in favor of the proposed facility. Clarke dismissed the “Send them somewhere else” crowd, reflecting a sympathy borne of personal experience for those suffering and an appreciation for the benefits of the mountain climate.

“I am most decidedly in favor of the proposed construction of this hospital on this mountain… both from a humanitarian standpoint and from the standpoint of one who has come to realize what the establishment of this proposed hospital means in the matter of the cure of those afflicted with a disease that, unless relief is given, must end fatally; and also from the standpoint of one who would protect this mountain from threatened spoliation. I know what my residence here has done for me: I think I know what it will do for those unfortunates who see only death on the one hand, and a possible restoration to health on the other. ”

Oliver P. Clarke (1847-1917) Resident caretaker of Grant Cottage from 1889-1917.

From The Gibbon Reporter - 9/21/1911

Before breaking ground, the company needed legal permission to purchase real estate for its humanitarian project outside the scope of its normal business operations. The company was at the forefront of “investing” in the physical welfare of its employees, including free healthy lunches at the home offices. The New York Supreme Court paved the way by deciding that:

““The duties of the employer to the employee have been enlarged in recent years, and are not merely that of the purchase of the employee’s time and service for money. The enlightened spirit of the age, based upon the experience of the past, has thrown upon the employer other duties, which involve a proper regard for the comfort, health, safety, and well-being of the employee. The reasonable care of its employees, according to the enlightened sentiment of the age, and community, is a duty resting upon it, and the proper discharge of that duty is merely transacting the business of the corporation.””

Architect D. Everett Waid (1864-1939)

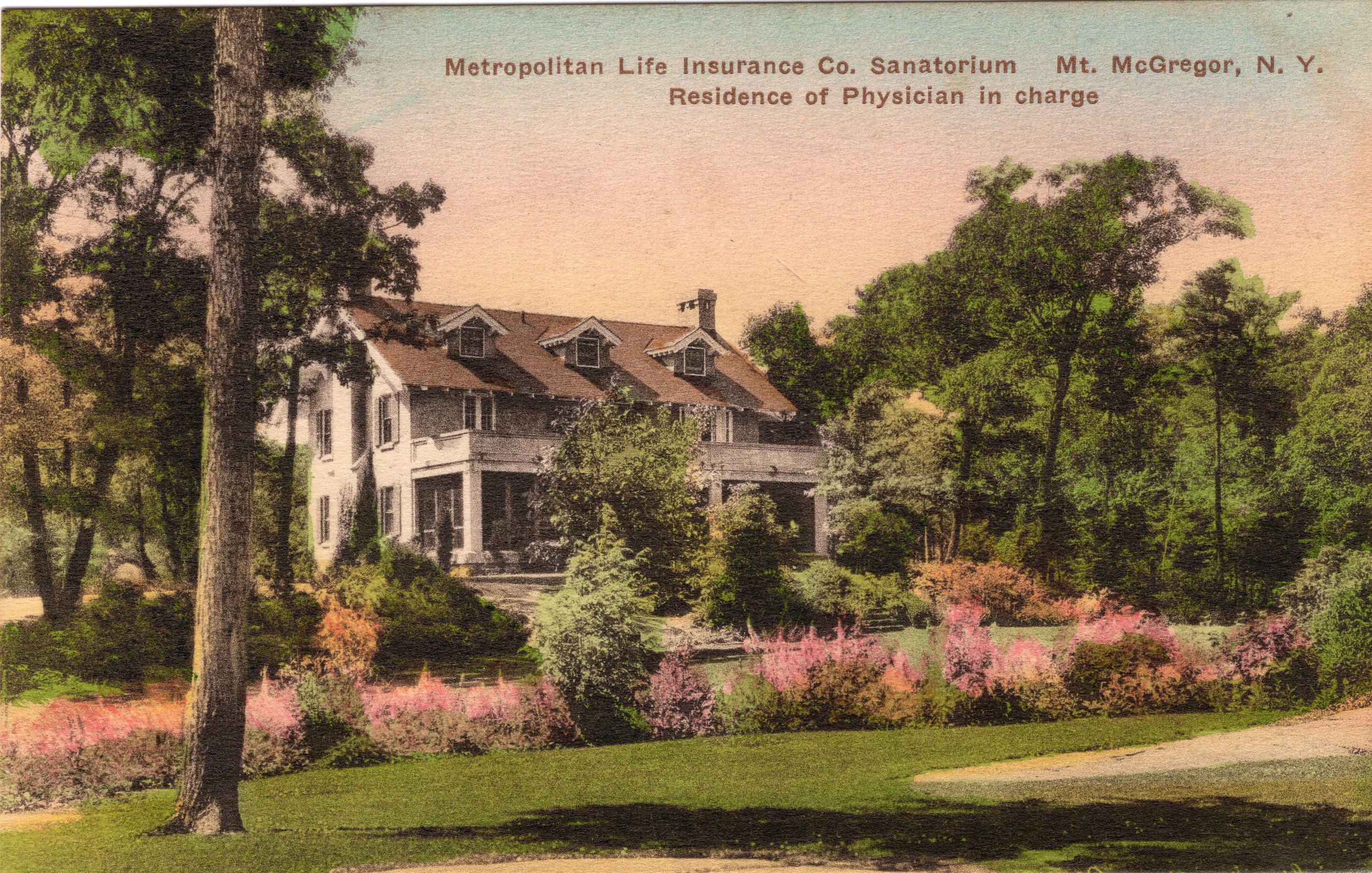

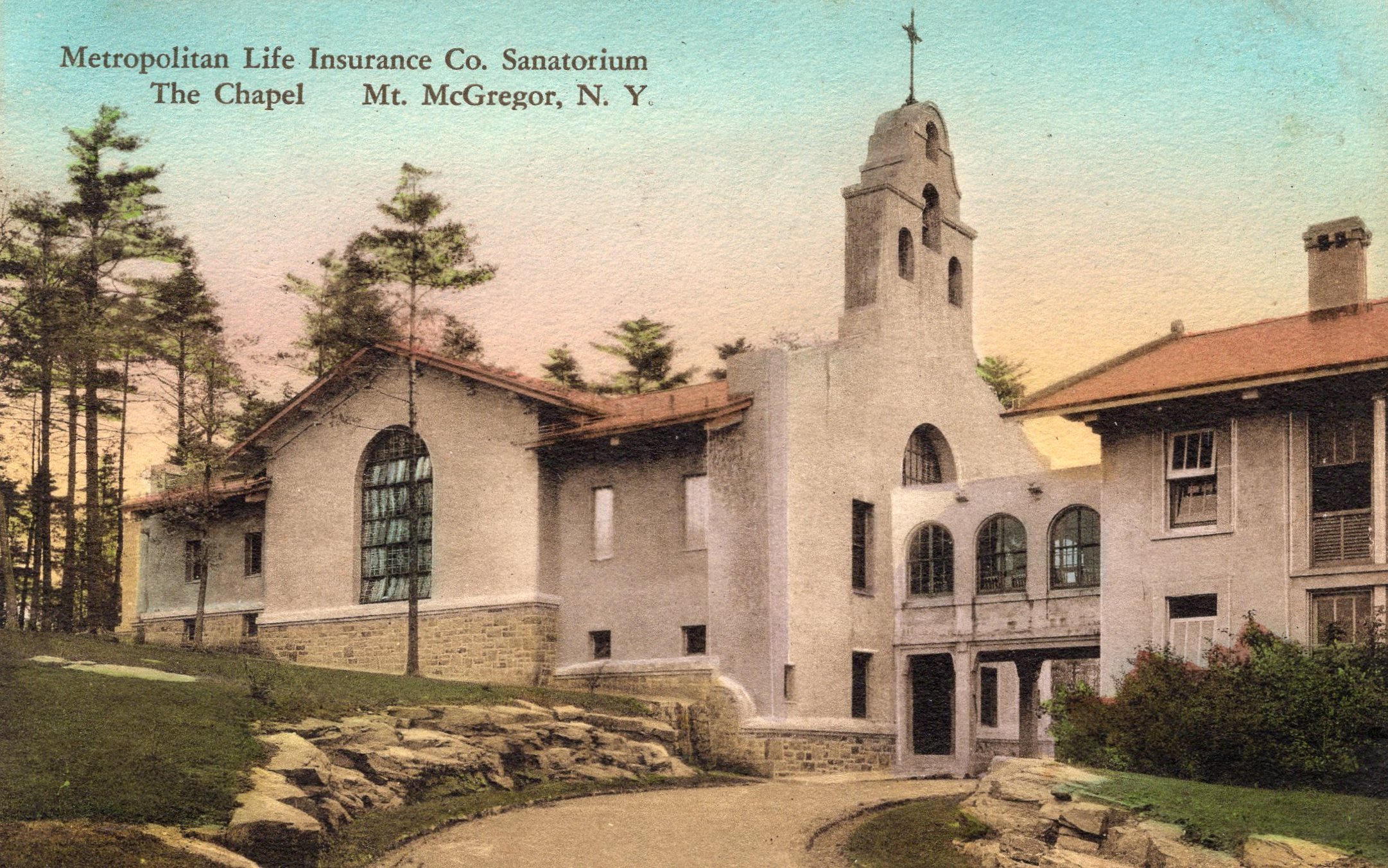

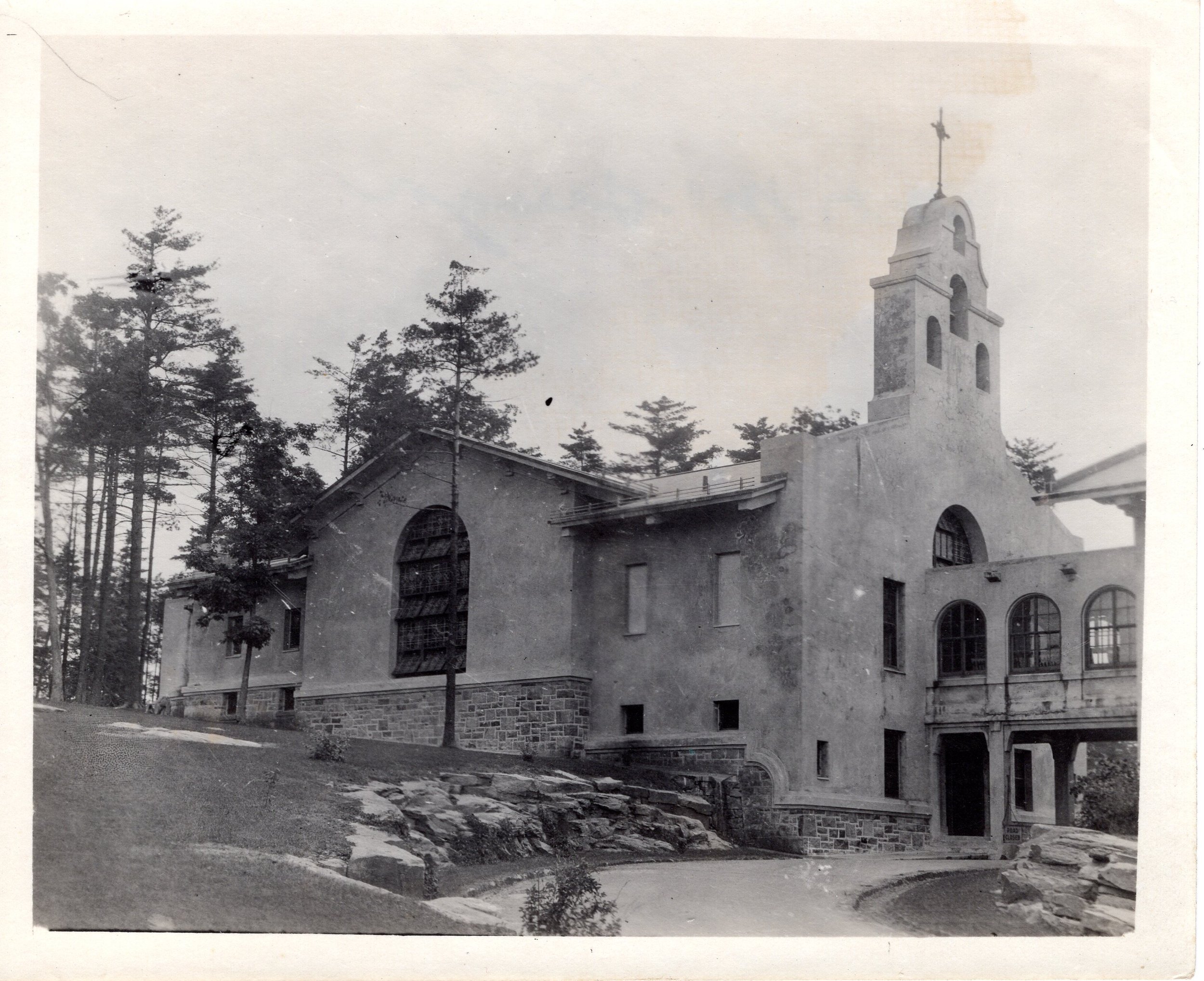

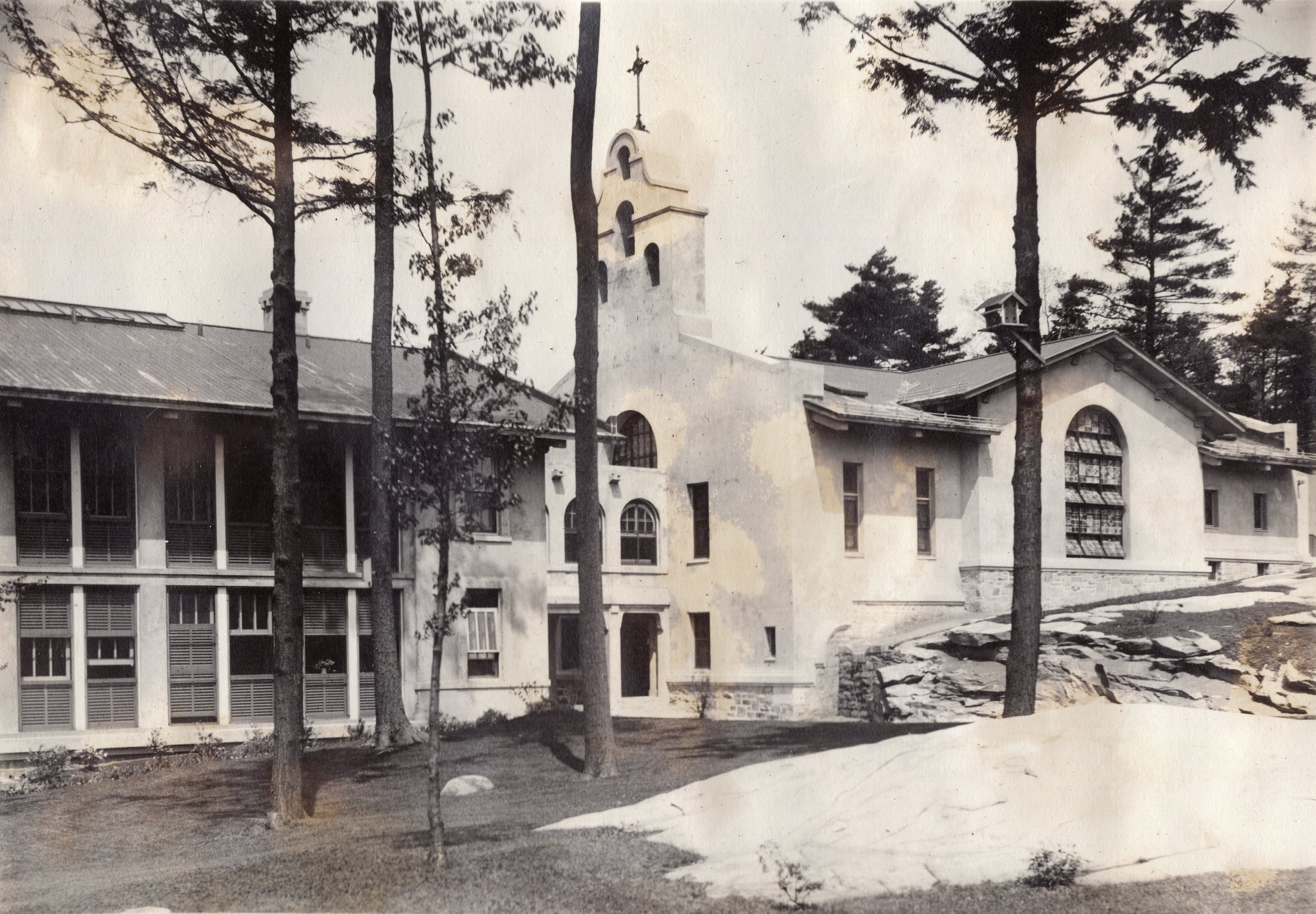

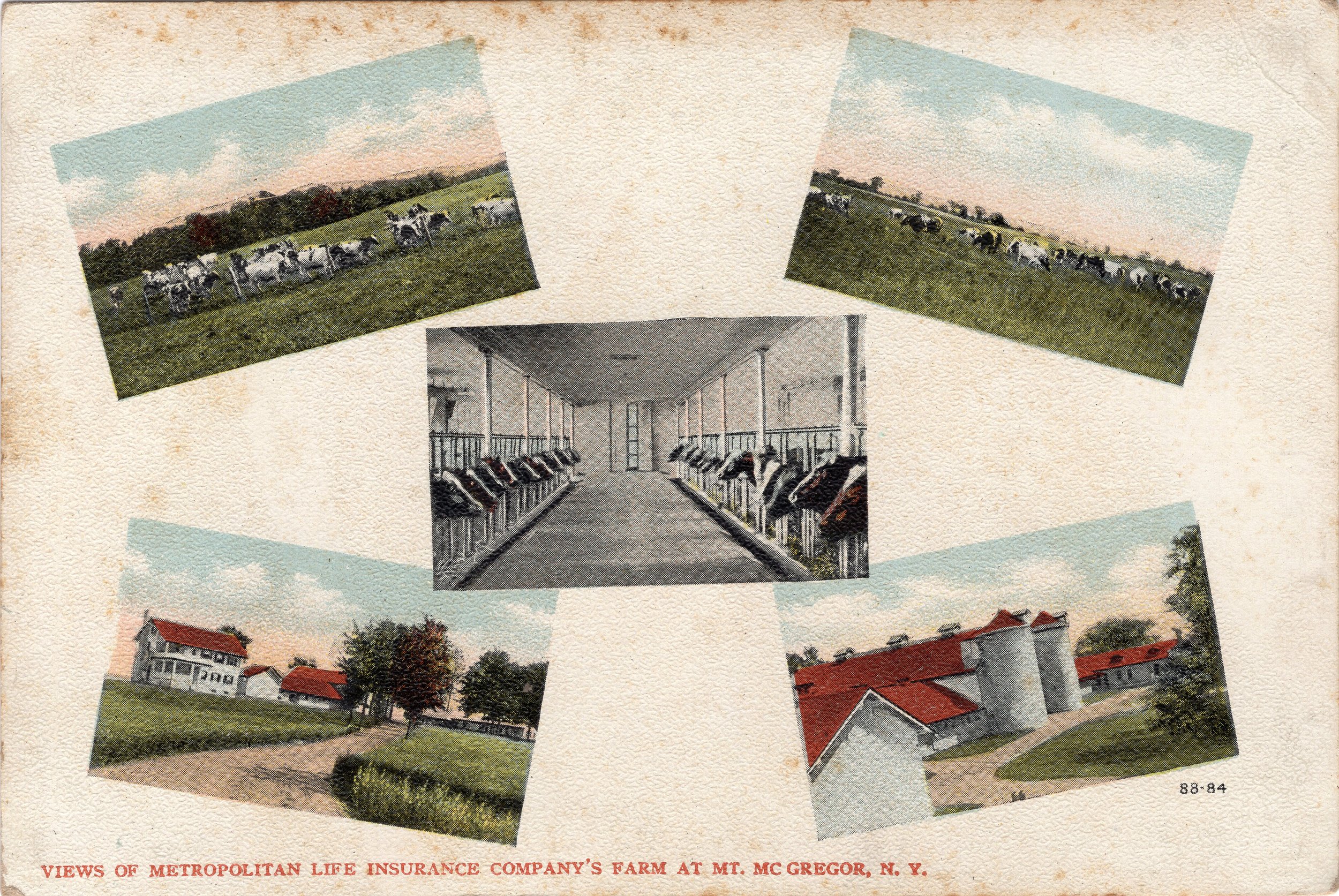

The company hired architect Dan Everett Waid to design the sanatorium on Mt. McGregor. He designed the complex in the American Craftsman style, which favored practicality over embellishment and the use of local materials. An exception would be the chapel which was designed in Mission Revival style. Waid traveled with a director of MetLife Dr. John H. Huddleston to numerous existing sanatoriums to gain insight and incorporate the best features possible. In addition to the main complex of buildings, auxiliary structures such as a steam plant, sewage treatment plant, and water storage tower would be needed for the self-sufficient operation. To provide the facility with fresh food, a 400+ acre farm would be acquired in the valley below the mountain to provide produce, dairy, and meats. Waid went on to have a successful career, with involvement in the Empire State Building and Rockefeller Center projects in New York City.

Architectural scale model of the “Hospital at Mount McGregor, New York” by D. Everett Waid from The American Architect 7/3/1918

Alternate angle of the Mount McGregor model showing the Grant and Arkell Cottages on the upper right by D. Everett Waid from The Intelligencer Vol. 8, 1915

Image showing a steam shovel used to move quarried stone for the construction of the buildings.

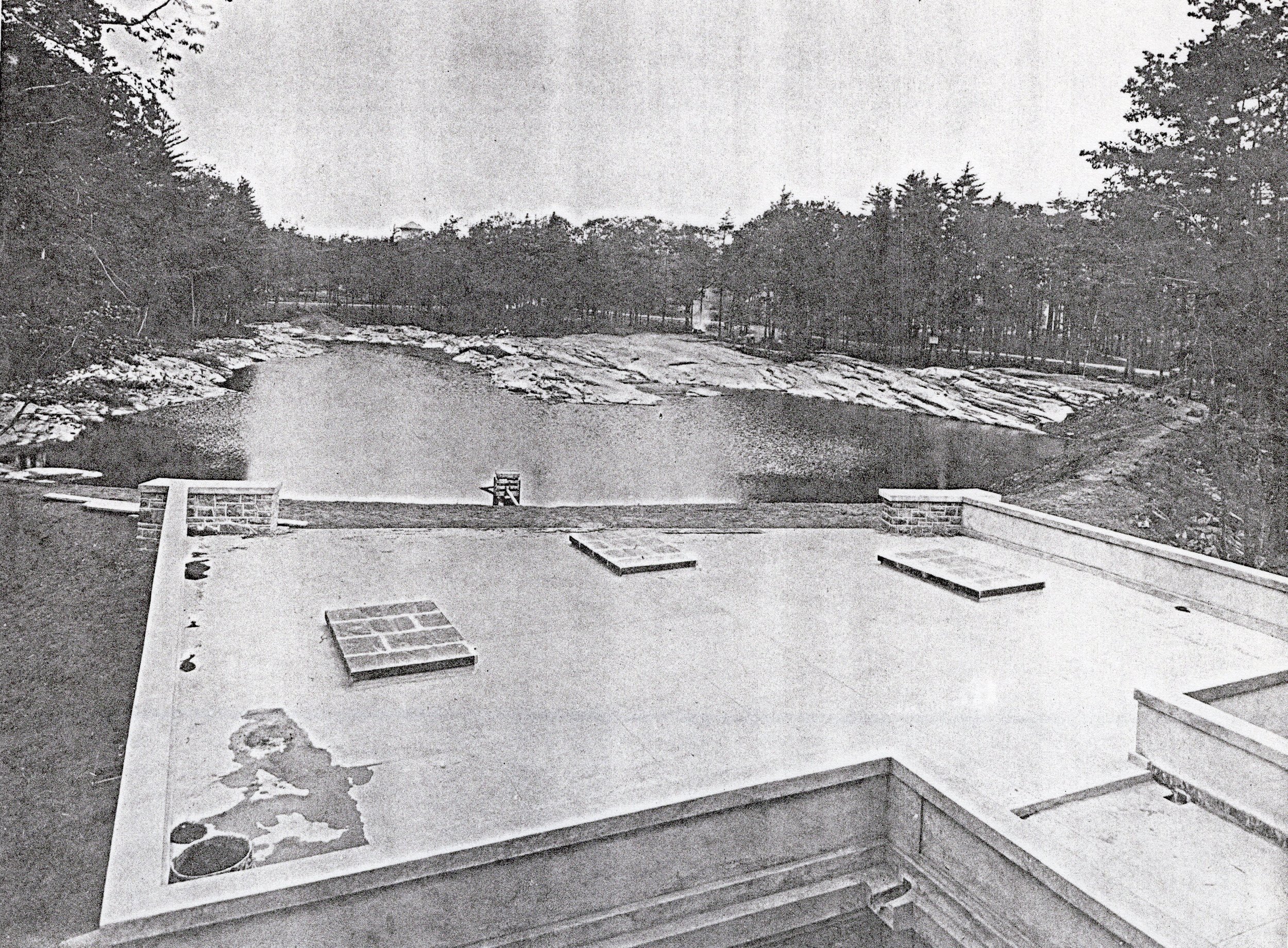

The initial stages of construction took place in January 1911, when surveyors laid out a new macadamized road route to replace the old “gutted earth road, barely four feet wide” and lumbermen cleared the trees for the construction of buildings. Digging for foundations, blasting of rock, and building of the main structures progressed throughout the year. The complex was constructed with an impressive 750-foot tunnel joining the steam plant to the main campus.

Image showing the construction of sanatorium buildings and the 750ft utility tunnel.

Forest fire burns near the sanatorium.

Despite the setback of the temporary worker’s quarters of the Flood and VanWirt construction firm burning down in January 1912, 300 workers continued to turn the site plans into reality. The work, especially the blasting of rock was dangerous and one of the Italian workers had his arm crushed by a stray boulder landing on him. Another stone flew 600ft striking a horse in the head and severely wounding it. Work continued into 1913 and narrowly avoided catastrophe in the form of wildfire in early July.

View of Natco Hollow Tile construction on the interior of the Rest House building.

Field stone masonry work of Ward VI.

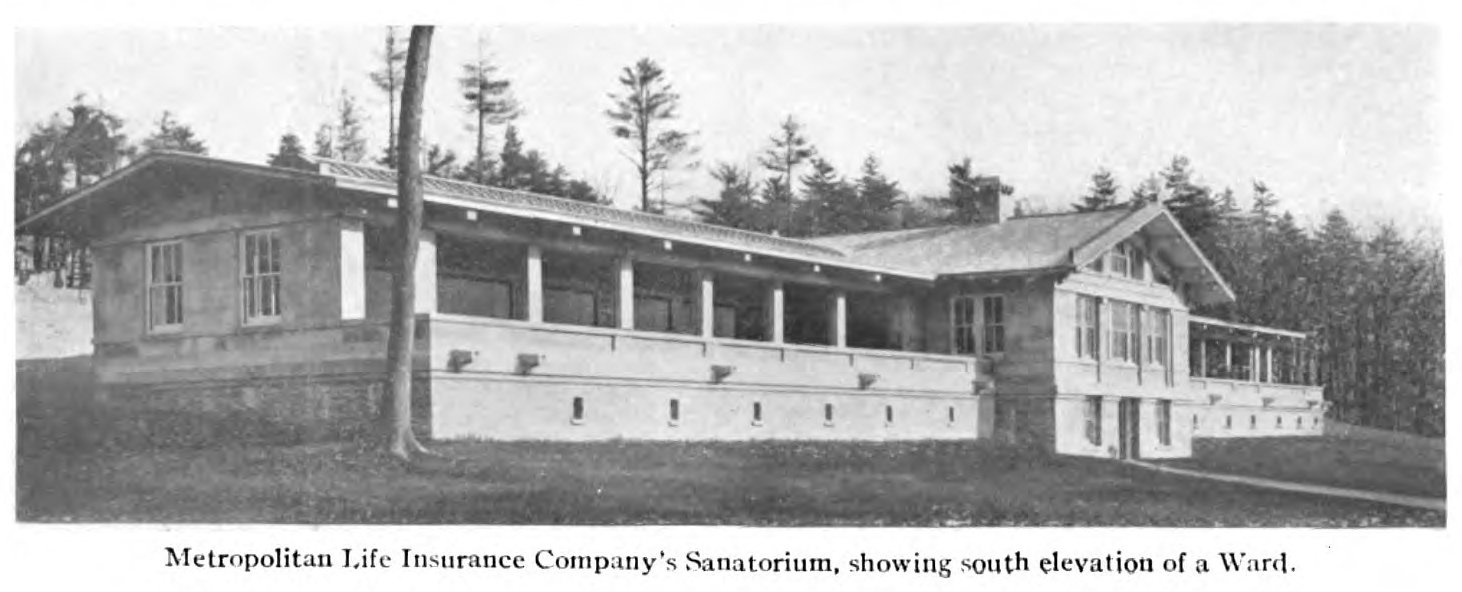

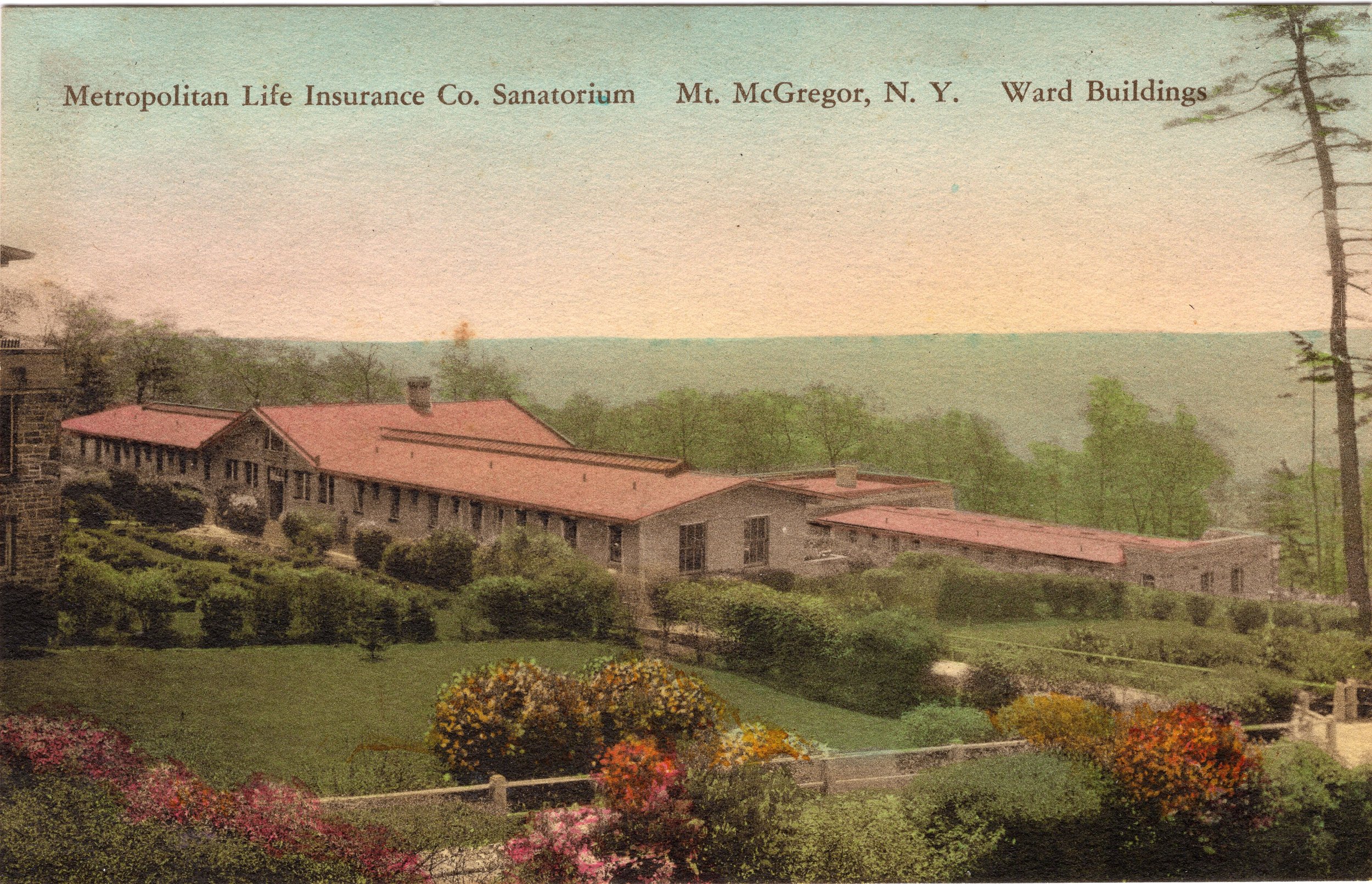

Two individuals who would go on to play pivotal and long-term roles at the facility were active in the construction phase; Chief Engineer Oscar Frick and Superintendent of Buildings and Grounds, Albert S. Coffin. The design was for constructing a campus of buildings to accommodate patients, staff, operations, and utilities. Planned were six patient wards on the eastern slope (providing abundant sunshine), a refectory for meals and activities, an administration building, an infirmary, and various staff housing structures. It would take five more years for the majority of the designed structures to be completed. The structures were mostly constructed with field stone foundations with hollow tile stuccoed walls above, though some utilized the field stone for the entirety of the walls. Red metal roofs gave the buildings a distinct look which was visible from the valley below.

An early depiction of the planned layout for the sanatorium showing six patient wards in front with an infirmary to the left, refectory in the center, administration building and Artists Lake beyond.

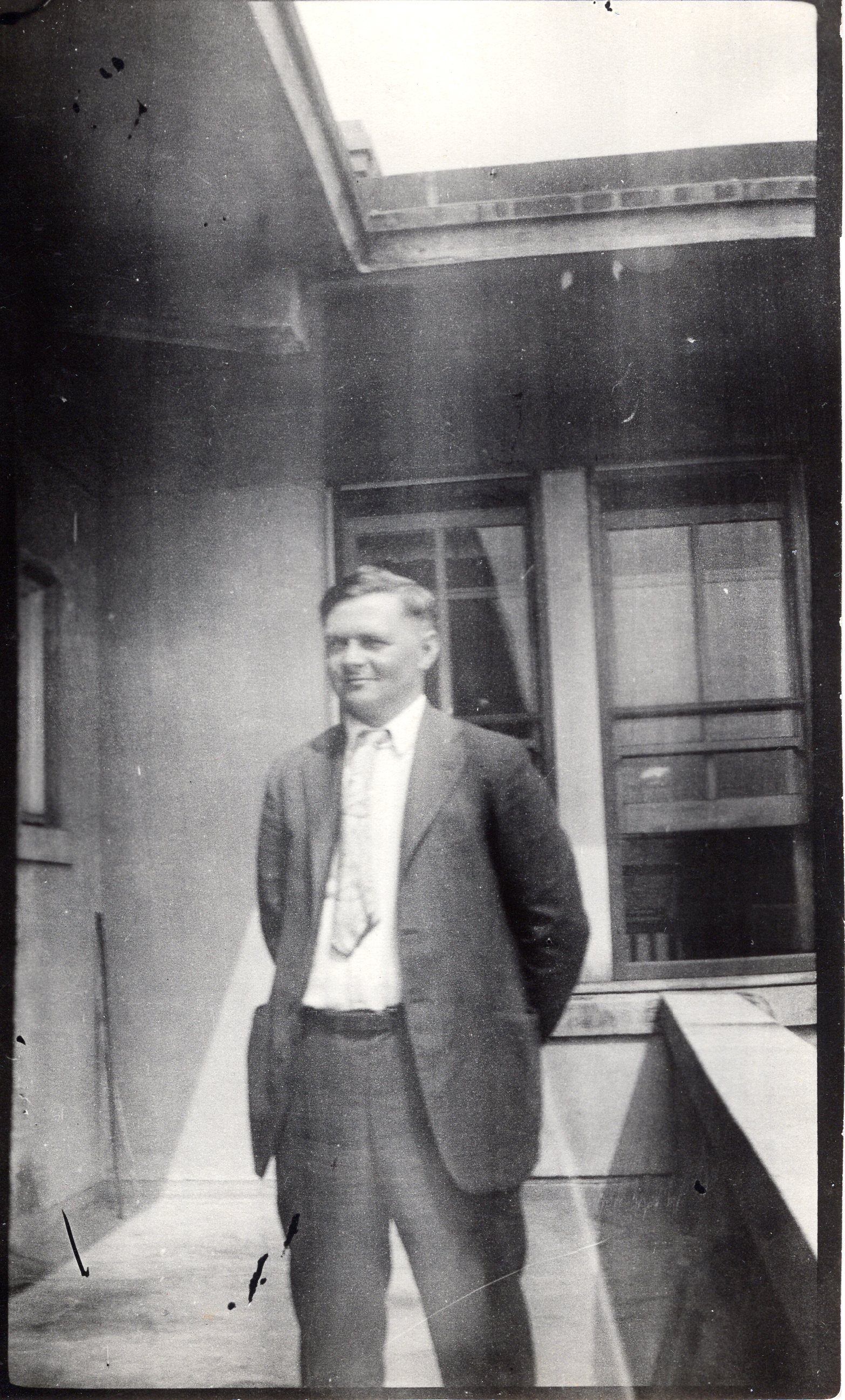

By the fall 1913, enough buildings were in place for some staff to move in. The first head physician was Dr. Horace J. Howk who had intimate knowledge of the disease he was to treat. When Howk was in his 20s he contracted TB and was treated at the Loomis Sanatorium in Liberty, NY, later joining the staff there before accepting the job at Mt. McGregor. The 35-year-old physician was described as hard-working, generous, and personable.

Dr. Horace J. Howk (1878-1926)

““The years [Dr. Howk] spent combating tuberculosis moulded his temperament and character in a way that found ample opportunity to assist and guide others over similar difficulties.””

Howk’s team was very modest initially with three doctors, eight nurses, and a chaplain. The first patient arrived on November 24, 1913, and was soon followed by 29 others before the end of the year. The patients and staff had to make do with what living spaces and amenities were available at that time while work continued to expand and improve the facility. By 1914, Howk would be accommodated in the Head Physician’s residence on the north side of Artists Lake.

From The New York Tribune 6/21/1914

On June 20th, 1914 company officials and some 200 others gathered on the mountain for a formal dedication. The President of MetLife was unable to be present but sent an address that acknowledged the mountain’s fame as the final home of Ulysses S. Grant: Some of those who spoke reference the sites of the American Revolution in the valley and the need for a war on the “White Plague.” New York State Senator Edgar T. Brackett, born near Mt. McGregor and a firm supporter of the project in the legislature, was on hand to celebrate the opening.

““Without strain of language, may Mount McGregor, already hallowed by historic association, be deemed as consecrated ground.” ”

Sanatorium patient Mark Crawford at the Eastern Outlook monument ca. 1921.

Some early patients were in temporary quarters right next to the historic Grant Cottage while two more wards were under speedy construction to increase the patient capacity from 73 to 177. Fourteen of the patients were housed in the 19th-century Arkell Cottage. Some of the lumber from the resort-era cottage was later used in the construction of the staff cottage built near the Power House in 1919. To further enhance the appreciation of the historic nature of the mountain, MetLife erected a stone designated U.S. Grant’s final view at the scenic Eastern Outlook surrounding it with a wrought iron fence to keep the souvenir hunters at bay. Civil War Veterans continued to hold ceremonies on the mountain into the early 20th century as well.

Early 20th century image of Grant Cottage showing the nearby Arkell Cottage in the distance.

Civil War veterans marching up Mount McGregor in 1915.

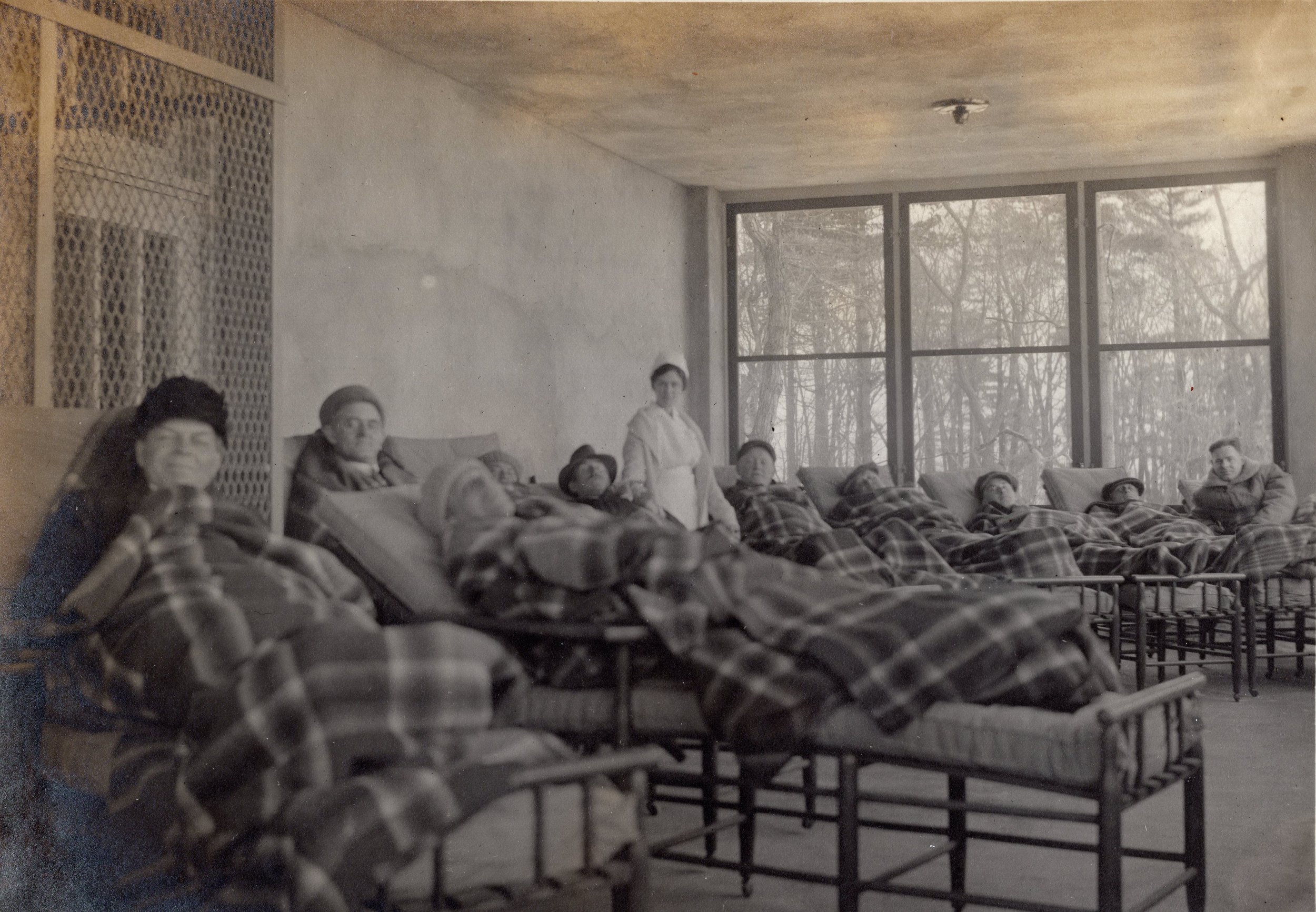

The patients would eventually be mainly housed in a series of six gender-segregated dormitory “ward” buildings on the southeast-facing slope built between 1913 and 1916. The ward buildings were designed to accommodate patients in the fresh air by having a covered veranda or “sleeping porch” equipped with bug nets as the main sleeping area. Two patients shared a dressing room and sink with communal tub./shower rooms in the center of the building. A social room was situated at the center of the building. No dining accommodations were necessary as patients were expected to walk the short distance to the dining hall at the nearby refectory.

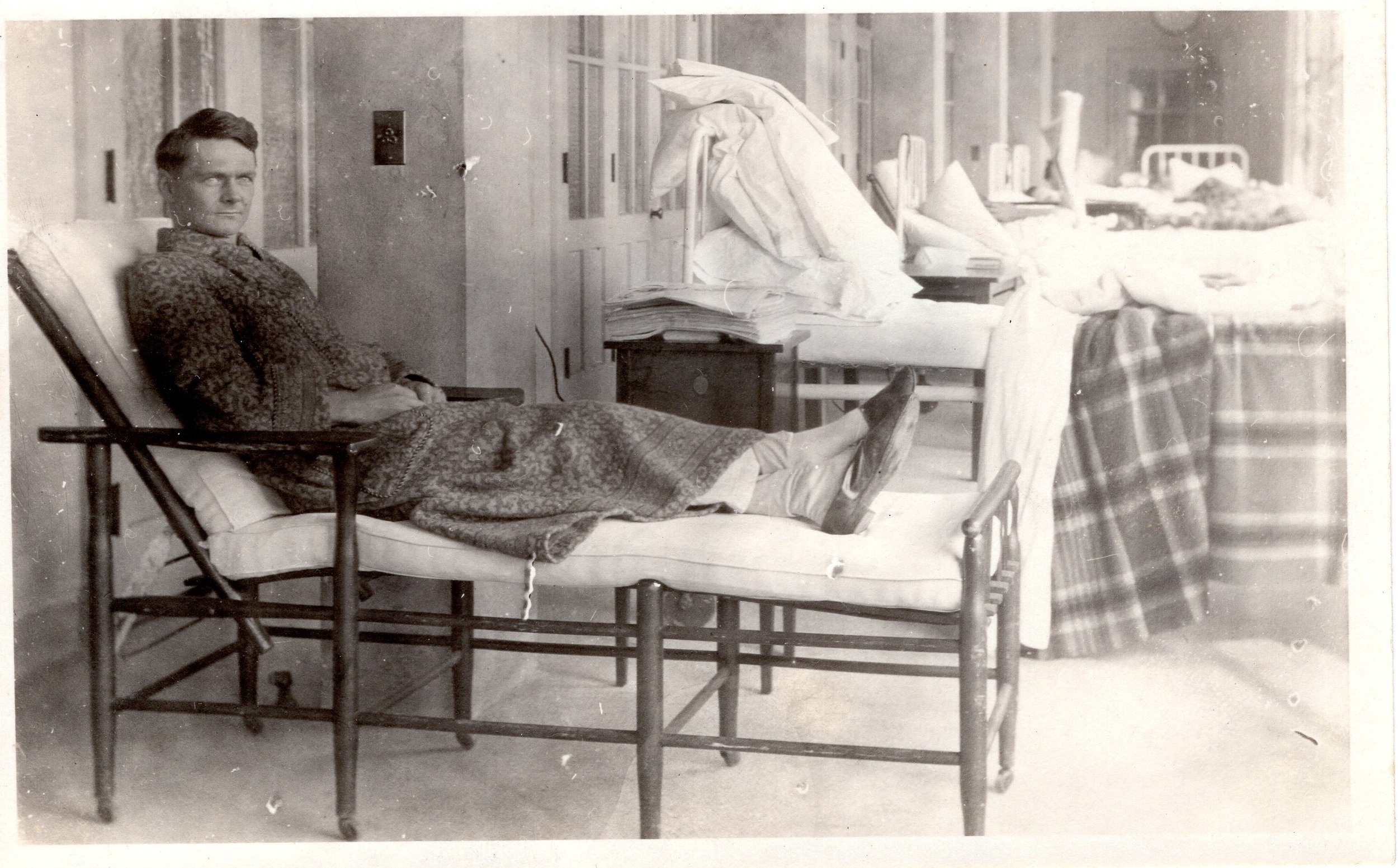

In its simplest terms, the sanatorium cure was a treatment protocol involving rest, exercise, fresh air, fresh healthy foods, and, when necessary, additional medical care. “Taking the cure” became the term for when patients rested on beds on exposed ward porches to maximize their exposure to fresh air.

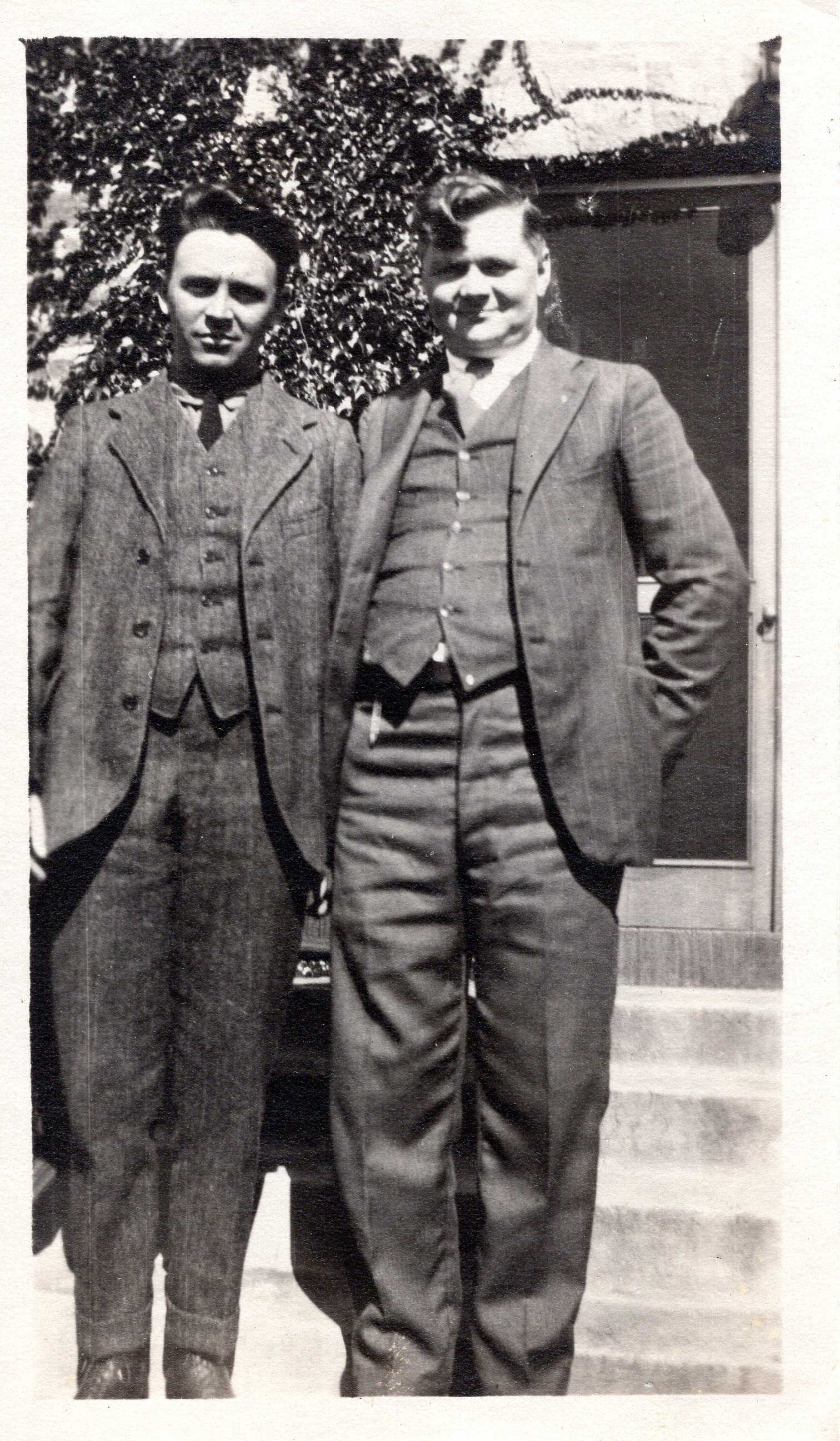

An example of a typical patient at Mt. McGregor was Mark Crawford. Like many patients, he was employed by the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company as an insurance agent. The Crawfords were a prominent family in Farnham, NY and Mark became Mayor of the rural village in 1914 at the age of 26. When Mark came to the San in 1920, he left behind his wife Caroline “Lena” and their 7-year-old daughter Marion. It could not have been easy for Mark to leave his family and travel 300 miles east to seek treatment, but at the time it was the only realistic option to restore his health. Many patients came from more distant locations including Canada for treatment. Most of the patients had to leave loved ones behind and visits with them were usually very limited during their stay if they were able to visit at all. The average stay for a patient was about 18 months, with some patients staying over a decade. Part of the treatment was to see that the patients gained a healthy amount of weight. One of Mark’s photographs from his time at the San wrote playfully on the back “How’s this. Sun shining in my eyes. Not quite as fat as I look.” After returning home, Mark remained active in his community serving as a justice, mayor, and board of education member. He never forgot the time he spent on the mountain or the friends he made, returning in later years for reunions. Fresh outdoor air and sunshine remained important to him as over a decade later Mark and his family spent a portion of the summer at Brant Park in a tent. After his wife Lena died in 1939, Mark remarried to a nurse, Dorothy Schorb, who had worked at Mt. McGregor.

Hot water bottle from Mt. McGregor (Wilton Heritage Society)

Original patient chaise chair from Mt. McGregor (Wilton Heritage Society)

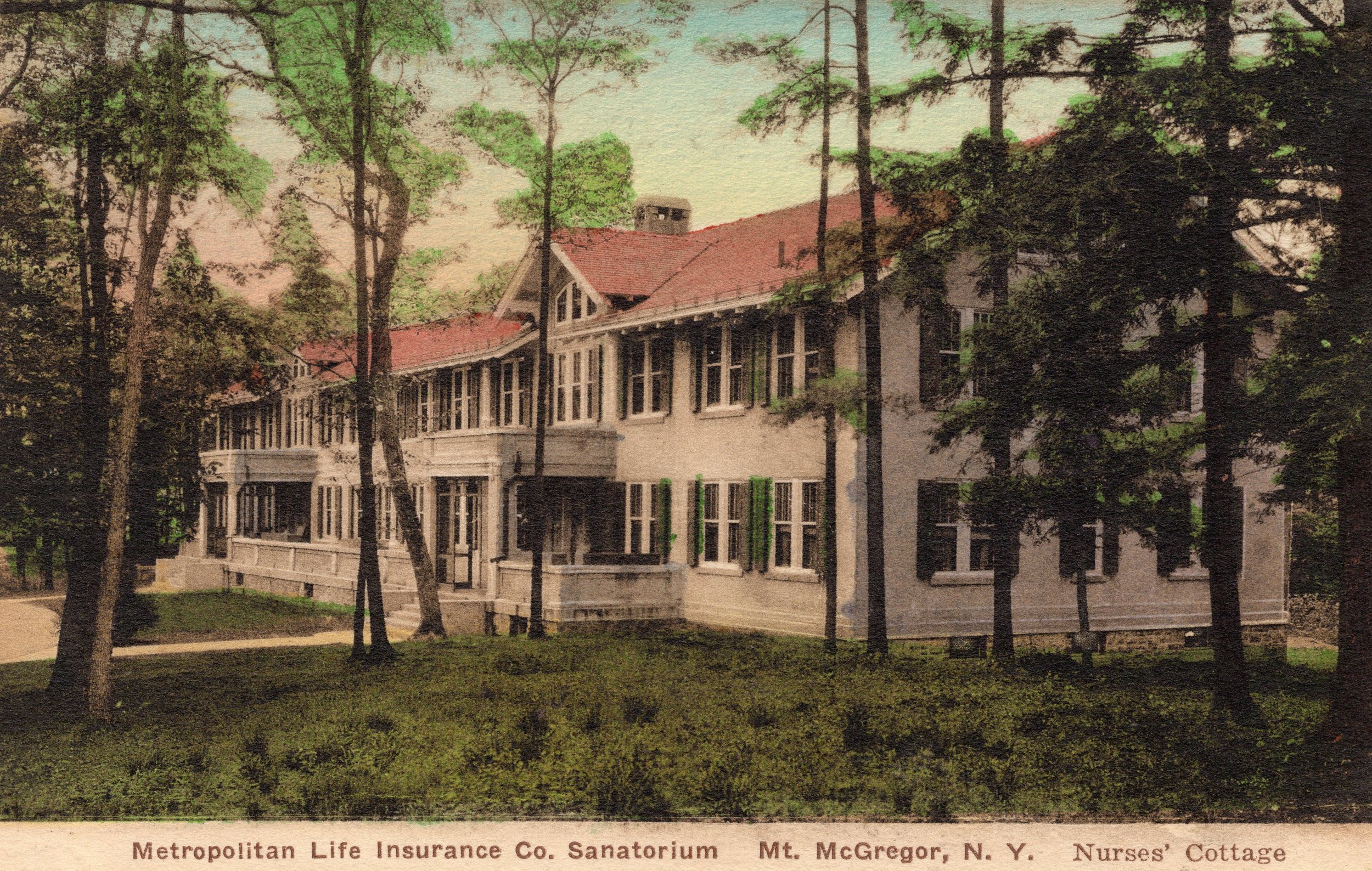

To guide and care for the patients was a dedicated staff of nurses. Aside from providing care to the patients, the nursing staff developed friendships and became part of the San community. The nurses resided in a dormitory near Artists Lake. There were numerous stories of employees finding love at the facility, one such story was nurse Etta C. Scoltock and chauffer Harry Clancy who were wed in July of 1920. Harry had served as a plane mechanic in the 814 Aero Squadron in World War I and Etta was born in Jamaica to an English mother and a Scottish father. A number of the staff were immigrants and/or from lower-income households. The existing staff was sometimes augmented by nursing students from nearby Skidmore College. Some of the students would eventually brought on as staff such as Cloyce Morse 1916-2007) who became a lab technician shortly after her graduation in 1940.

Cartoon from The Mt. McGregor Optimist

Etta C. Scoltock Clancy with patient Mr. Goldenberg

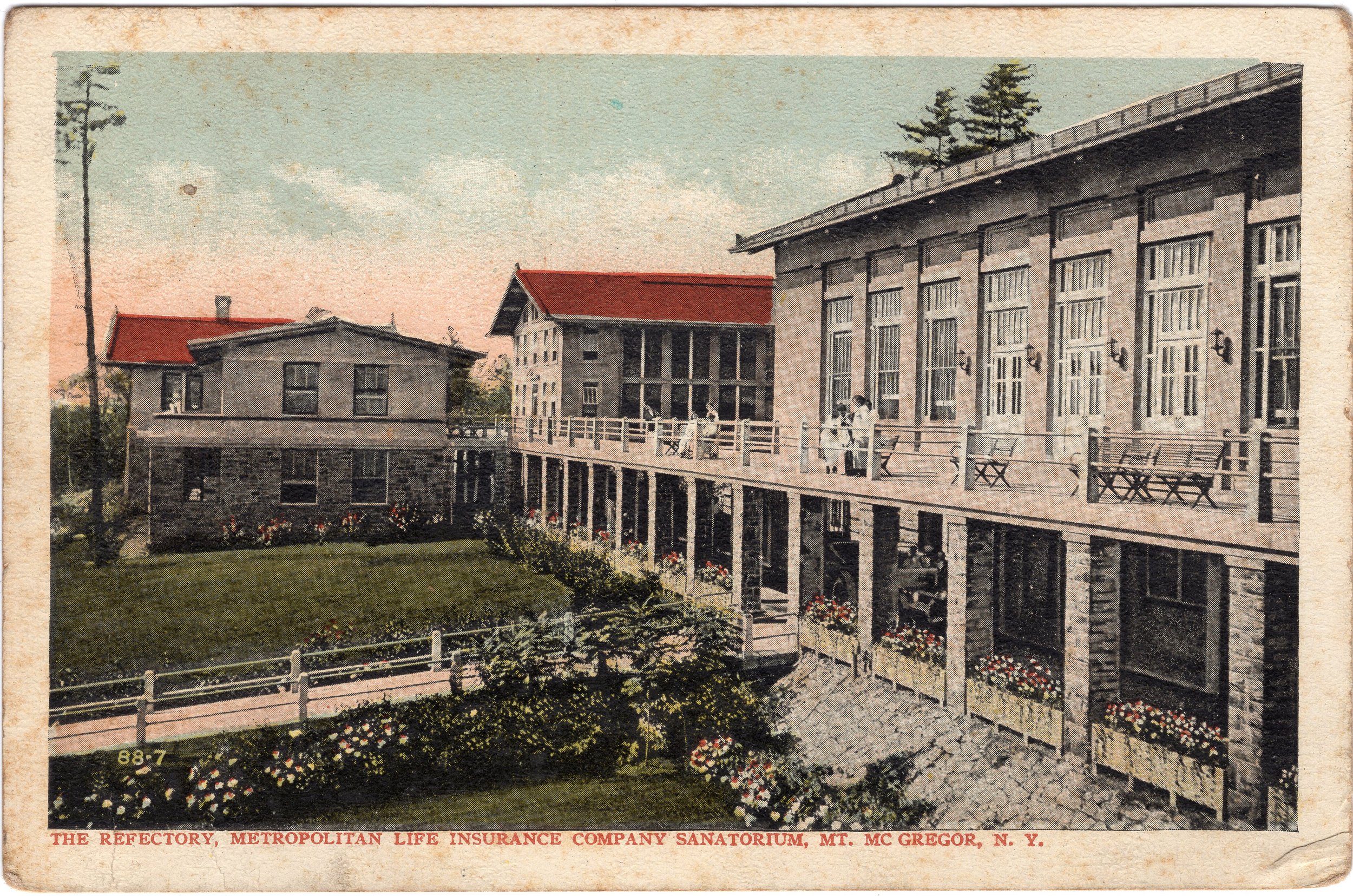

A nurse pushing a patient in a wheelchair on the elevated walkway.

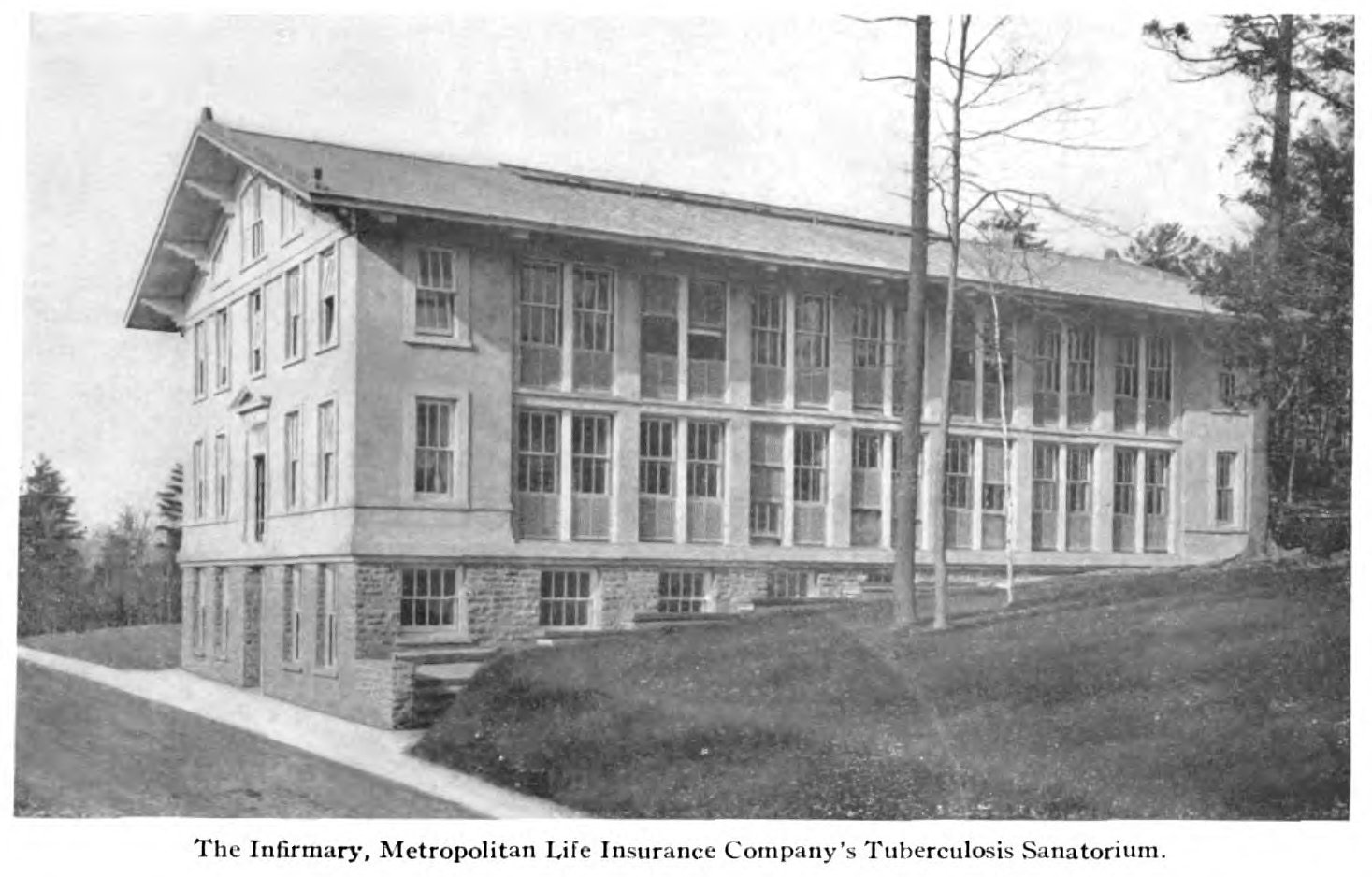

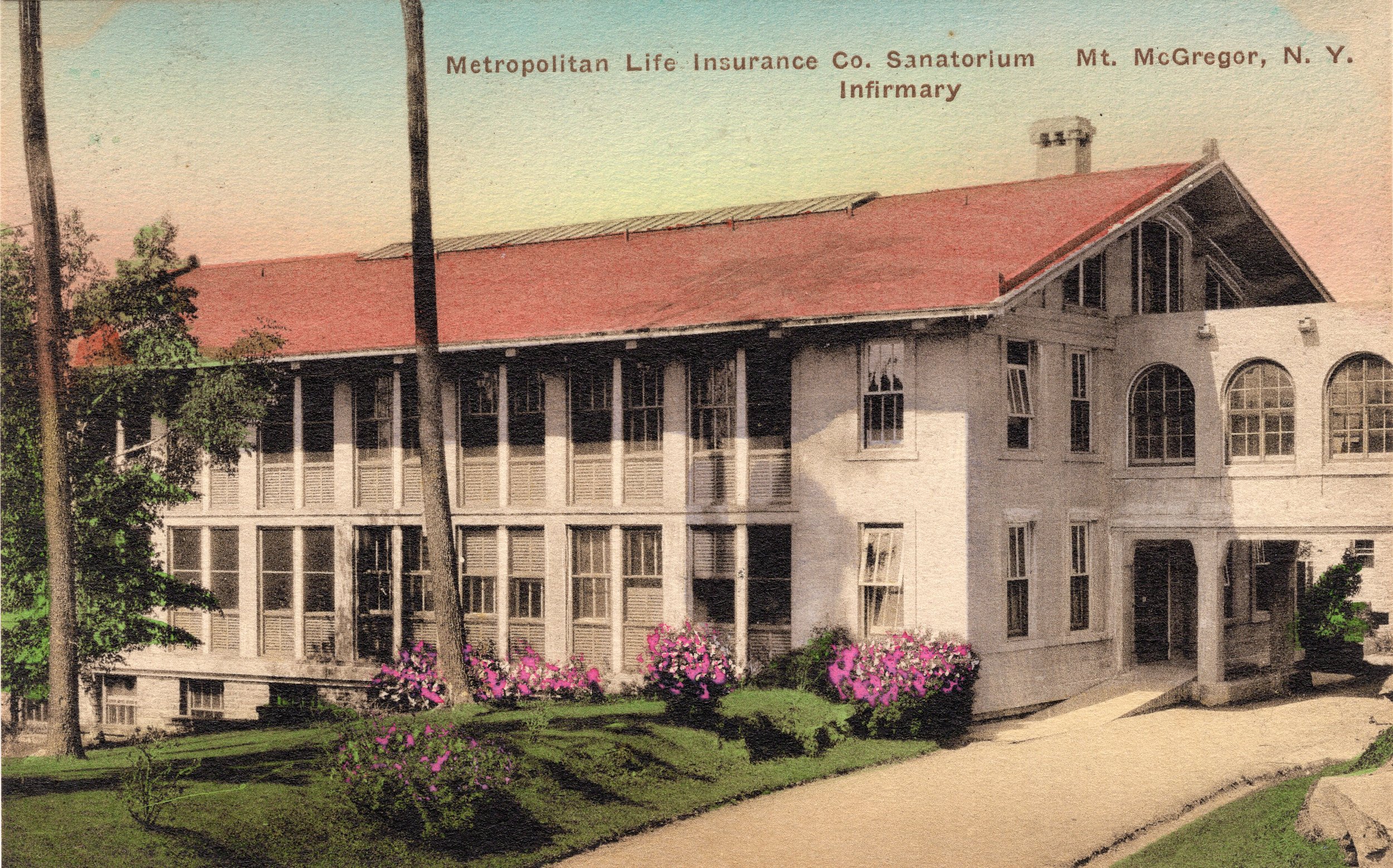

Patients requiring enhanced treatment or care were accommodated in the infirmary. The infirmary housed the x-ray equipment and its own kitchen to prepare meals for the bedridden patients. Due to the scale of the facility, the medical staff utilized a series of phone lines and switchboard installed for rapid communication between various buildings. To make transportation of goods and patients easier a stone and concrete elevated walkway was erected connecting the Refectory with some of the other adjacent buildings. These wide walkways also provided a place for outdoor socialization with tremendous views of the valley as well as protection from the elements when walking underneath them.

An x-ray image showing a tubercular lung (1921) from the Journal of Outdoor Life

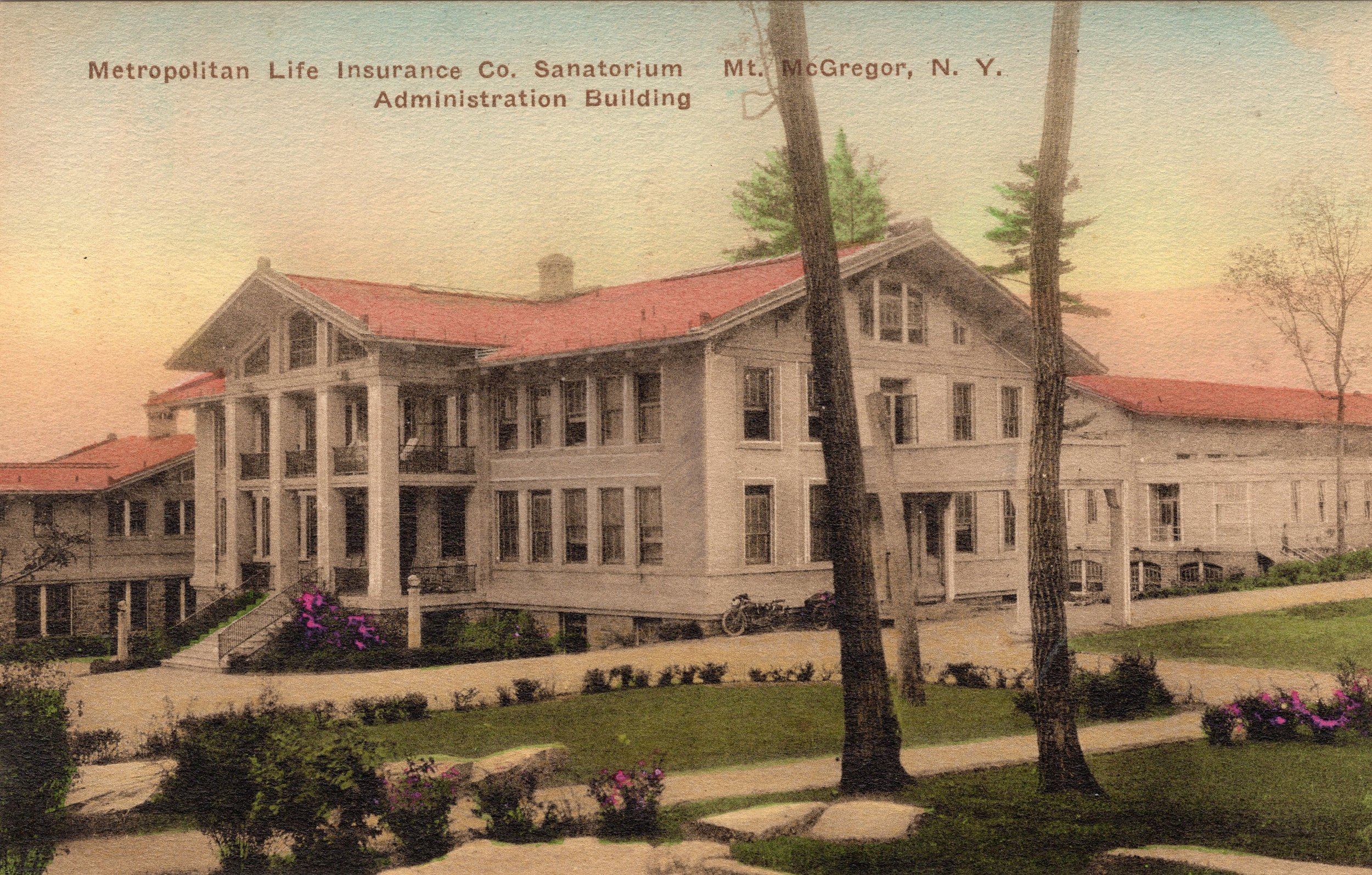

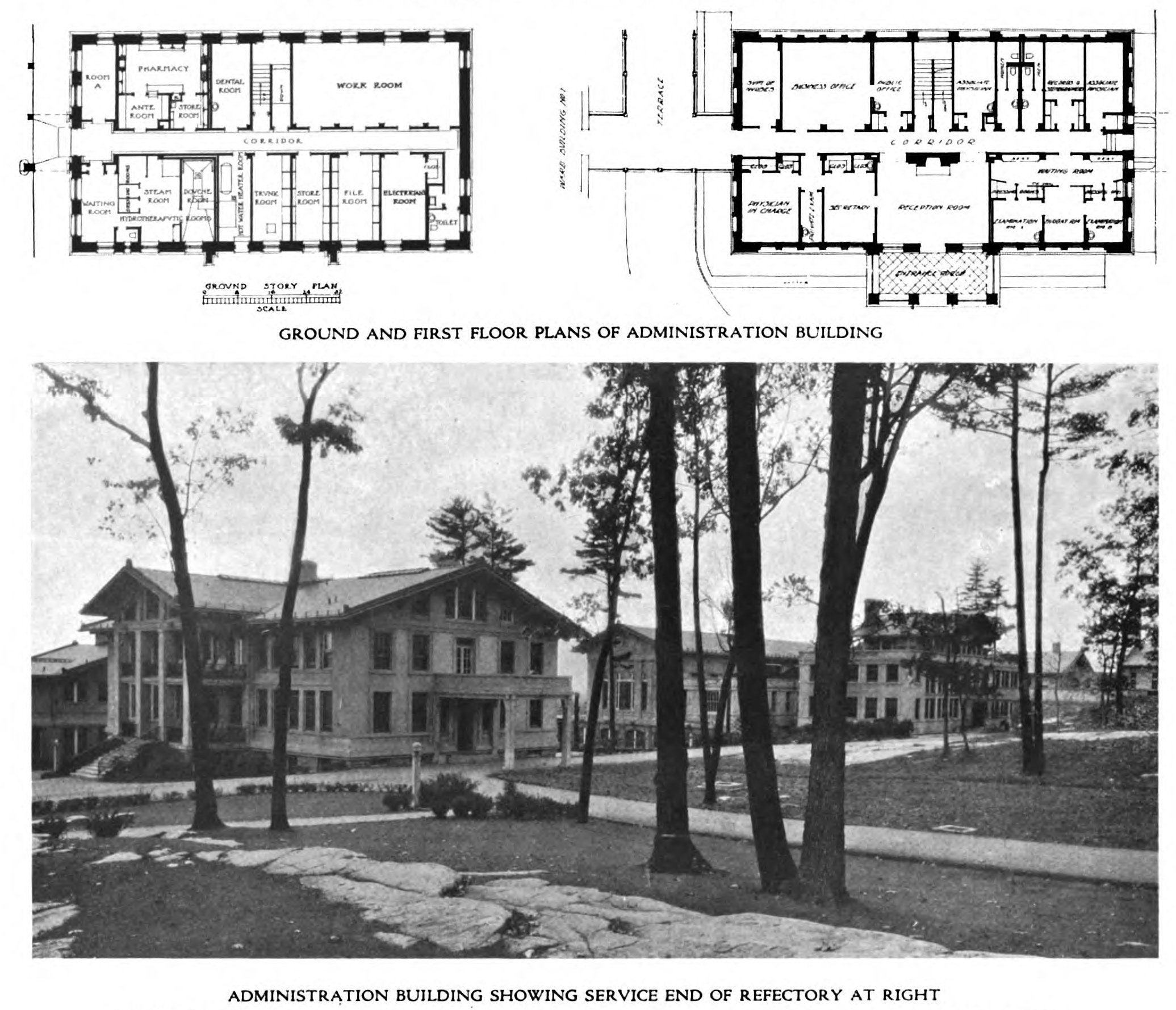

The multi-columned administration building was the main entrance of the facility. It is where the new patients came for evaluation and orientation. A dental office, pharmacy, and facilities for hydrotherapy treatments were located on the ground floor. Medical staff had offices and living rooms on the second floor of the building while the upper floor housed an extensive medical library.

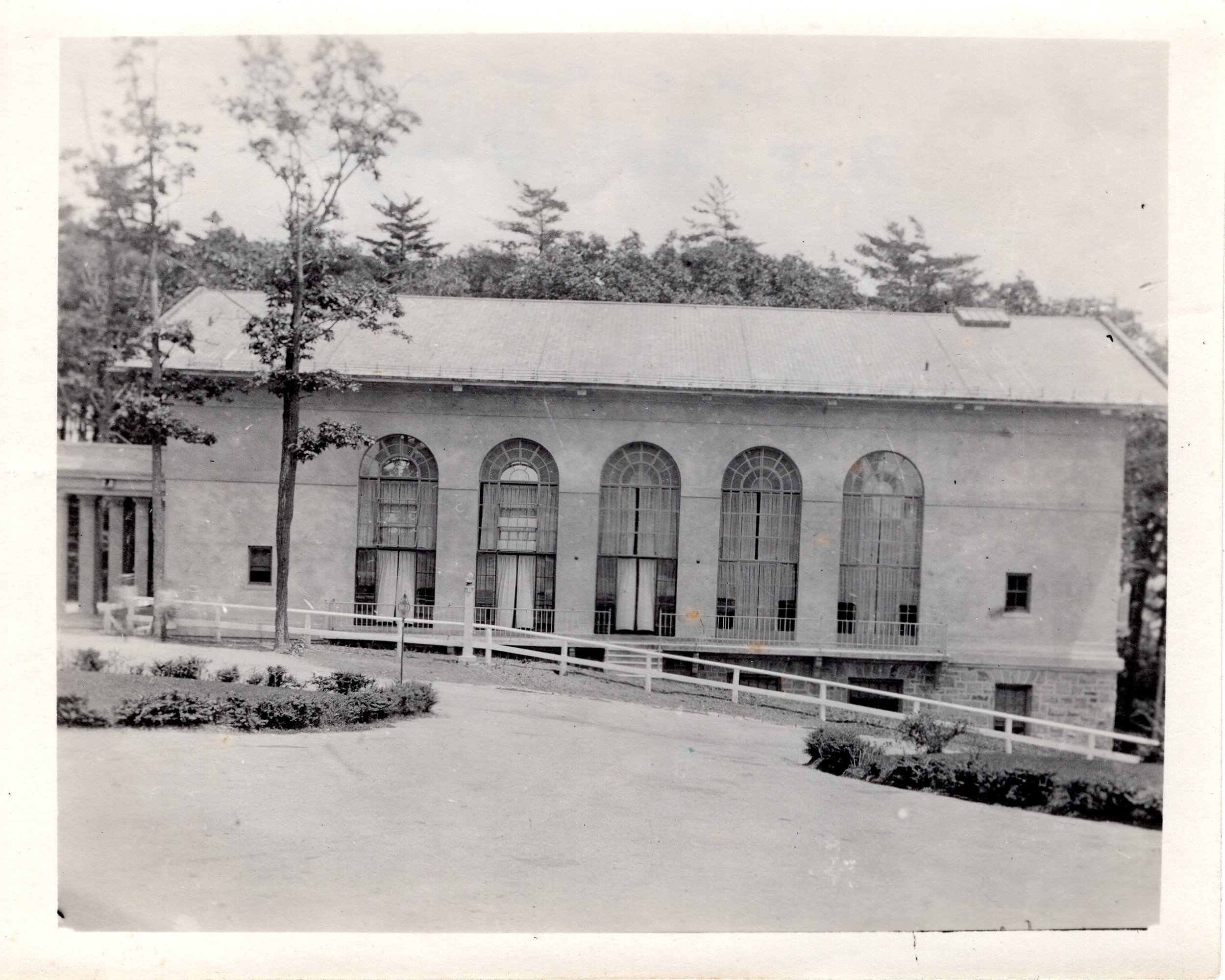

The patient culture was emerging as the first issues of the Mount McGregor Optimist were published in 1914 which would eventually flourish into a very popular and well-circulated journal both on and off the mountain. The Optimist provided a way for patients and staff to chronicle the events on the mountain as well as express themselves in various creative ways. Humor, prose, and even cartoons helped shape a healthy and thriving community at the sanatorium. The patients referred to the facility affectionately as the “San” and many established close bonds with their fellow patients and staff, even to the extent of organizing reunions of former patients. The hub of the community, especially in the early days of the facility, was the Refectory. This building provided space for communal meals, events, a library, and recreation. The spacious dining hall which hosted a variety of community events was 132 feet long and 32 feet wide with ceilings 24 feet high. An official post office was opened there in 1914, putting the community on the map and, as evidenced by the many postcards, providing a vital communication pipeline to loved ones back home. A company store also provided residents with easy access to magazines and other supplies of life which accepted payment tokens. A game room with a billiards table provided a competitive diversion. The San community would quickly grow to 350 individuals (approximately 200 patients and 150 staff) by 1920.

Trade token for use at the Mt. McGregor company store.

Plate from the Mt. McGregor sanatorium marked “1929”.

During his decade-long battle with TB at Mt. McGregor, Jeremiah F. O’Neill became the much respected and talented editor for the Mount McGregor Optimist. He helped the publication in its mission to “disseminate good cheer and scintillating humor, bolstering and supporting his fellow sufferers in their fight against their disease.” O’Neill, who also edited a series called “Joy Flingers: A Department of Cheer” to Journal of Outdoor Life published by the National Tuberculosis Association. At Mt. McGregor, he served as an assistant postmaster, actor in plays, and orator, serving as an example of the active and supportive culture at the San.

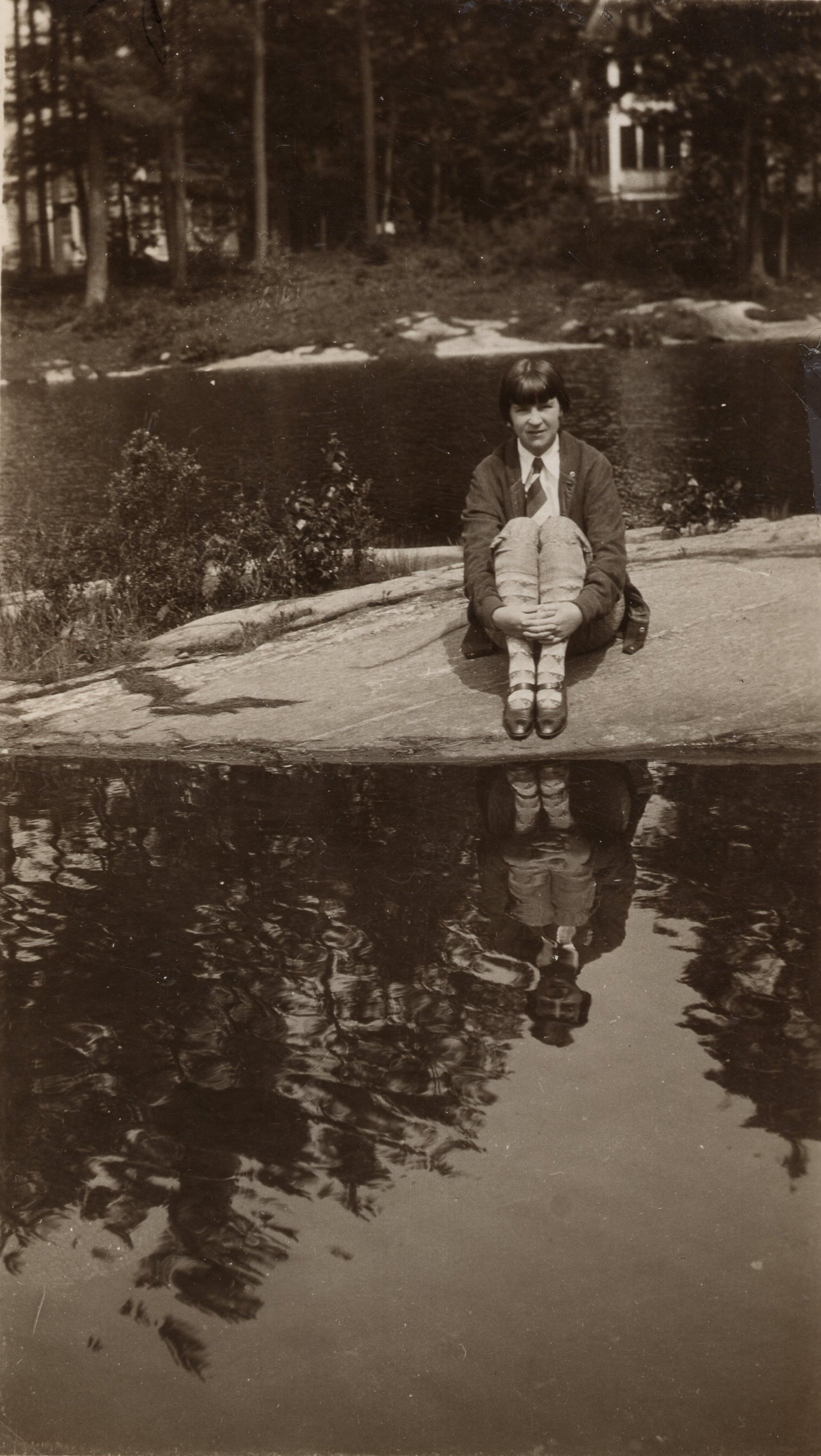

Sometimes patients were not employees of Met Life. Suye Narita had been brought to the United States from Japan in 1907 by medical missionaries. She contracted TB as a teenager and was sent to Mt. McGregor for treatment. Suye was successfully treated and moved in with Mr. & Mrs. Clarke at Grant Cottage. She served as librarian for the over 3000-volume San library for over a decade and was a resident of the mountain for 70 years. Suye served as editor of the Mt. McGregor Optimist after O’Neill and was a frequent contributor to the publication which had a circulation of over 4000.

Suye Narita at the San in 1922

The San library in the lower level of the Refectory.

An ice sculpture of General Grant by Dr. Neeb from The Intelligencer 1915

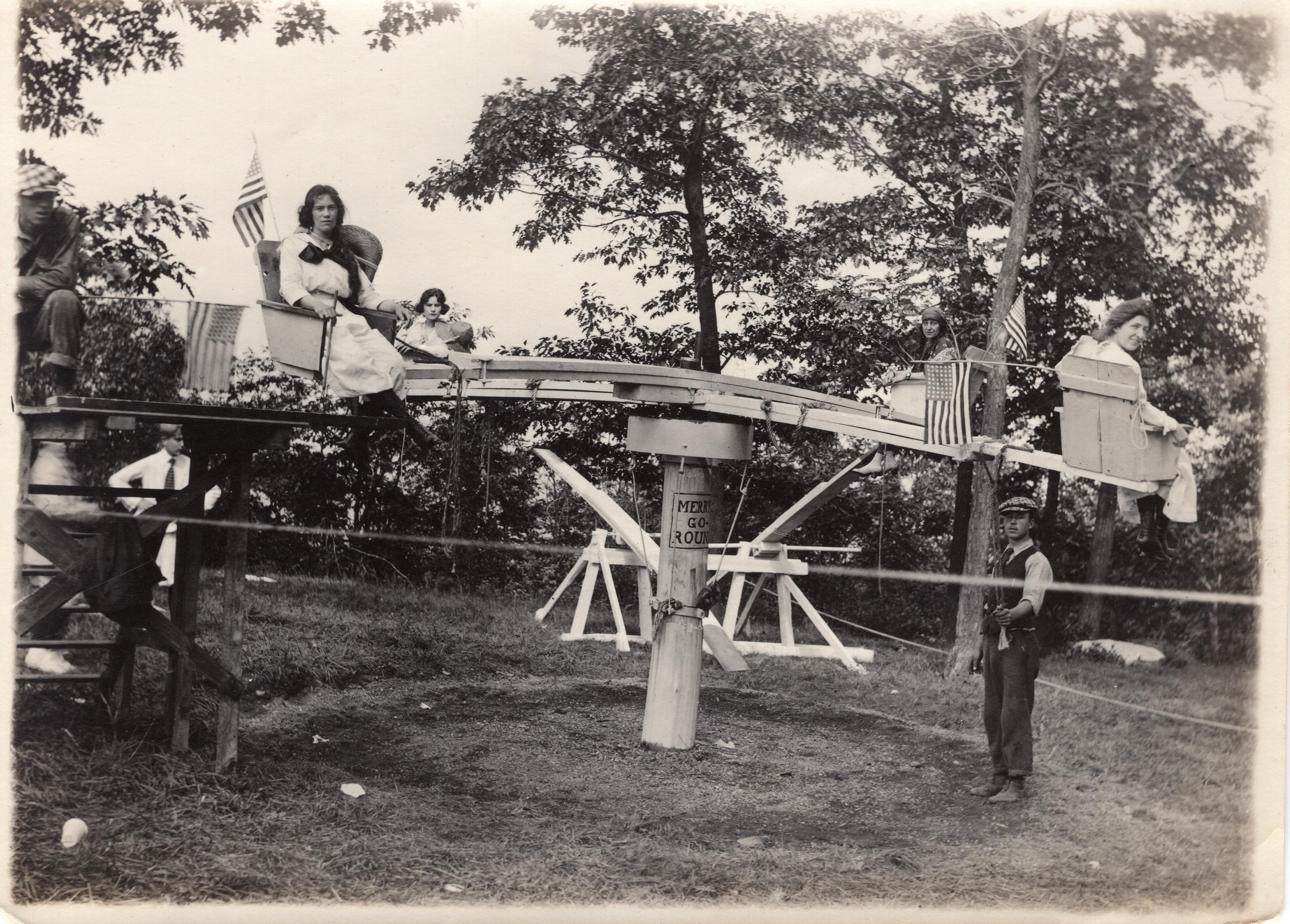

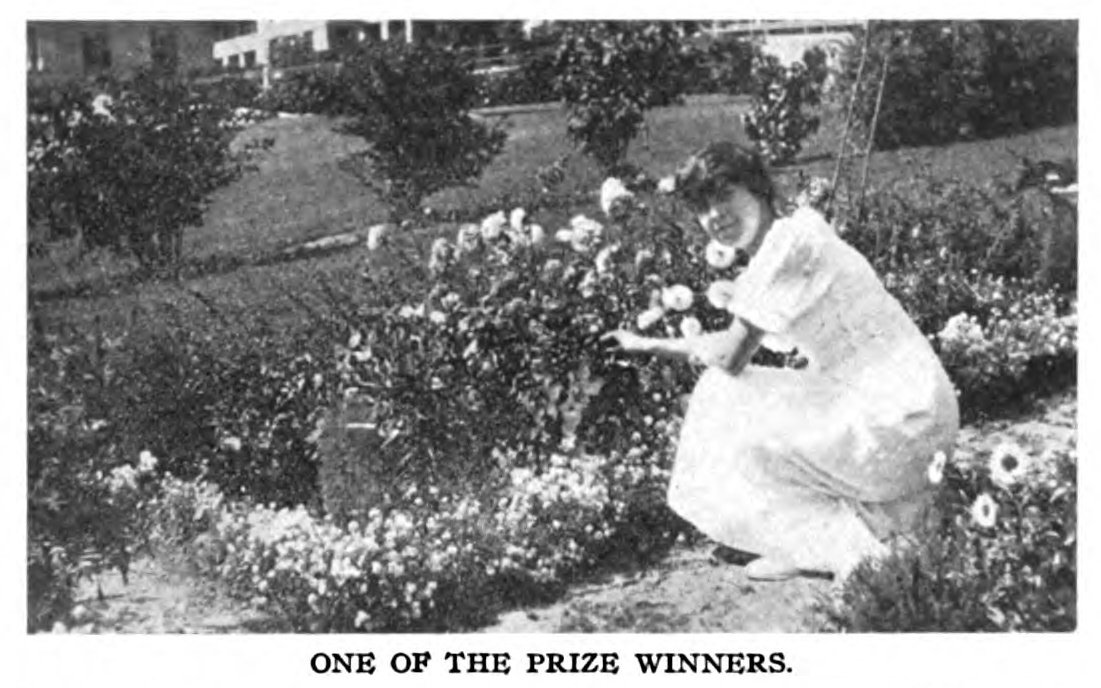

Fairs, parades, plays, and other social events were frequent at the San, helping to foster a sense of community and improve morale. The Mount McGregor County Fair was a popular annual event featuring contests, games, makeshift rides, costume contests, and a parade. The area of the old Hotel Balmoral was used as the main fairground. The facility also catered to shooting sports with a rifle target range. Other outdoor pursuits such as hiking on the miles of forested trails, swimming and fishing in the lakes, and picnics at the overlooks were popular among residents and encouraged by the staff for the wellbeing of the patients. The patients formed theater troupes and an orchestra and put on performances. All this was recommended by Dr. Howk to keep their minds occupied and provide useful life skills. Some patients as well as staff worked with materials on hand to create art such as fungus art and ice sculptures.

Fungus Art by “E.D. Smith” source: Folklife Center at Crandall Public Library

Fungus Art “Chapel + Infirmary -by- Walter Jagarfski Aug. 22, 1937” source: Folklife Center at Crandall Public Library

Baseball diamond on Mt. McGregor ca. 1920s

The San also featured the American pastime. A baseball diamond was created at the fairgrounds complete with bleachers. A team of patients and staff were named the Mount McGregor Marvels and played against other local teams.

From The Post Star 8/9/1924

The Mount McGregor Marvels baseball team at Mt. McGregor ca. 1920s

Spectators and seated players at the Mt. McGregor baseball field ca. 1920s

Footlight used at the Mt. McGregor auditorium. (Wilton Heritage Society Museum)

During a fifth anniversary celebration in November 1918, the new auditorium was dedicated, providing a standalone venue for performances and moving pictures which had been brought to the mountain as early as 1915. Many live performances of theater and music were offered, including many by local groups and student organizations. The building featured a 400-seat theater as well as a lower level for recreational crafts and vocational training such as cooking classes.

Mt. McGregor cooking class from Journal of the Outdoor Life 1922

Marble and brass pulpit in St. Mary’s Chapel.

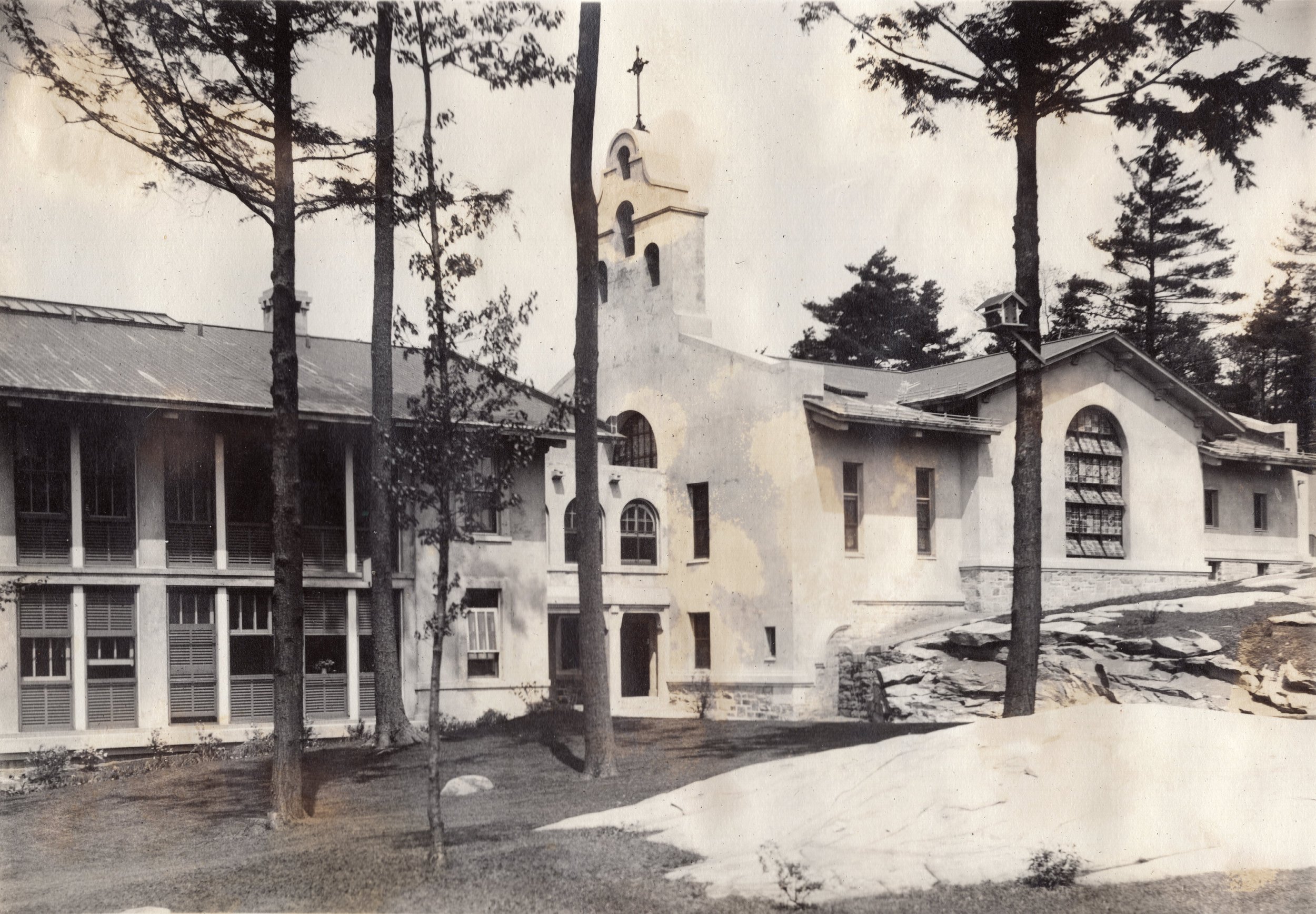

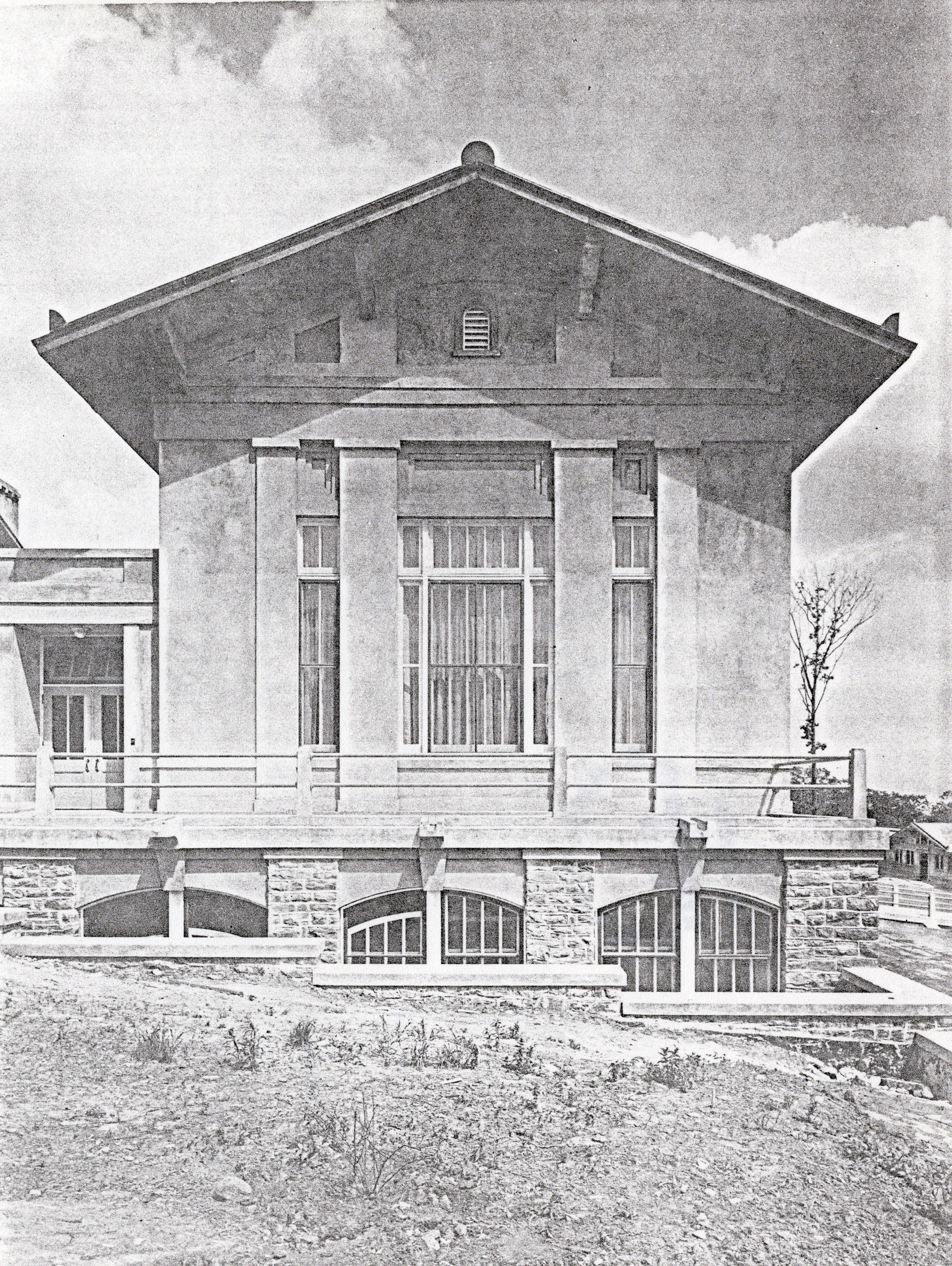

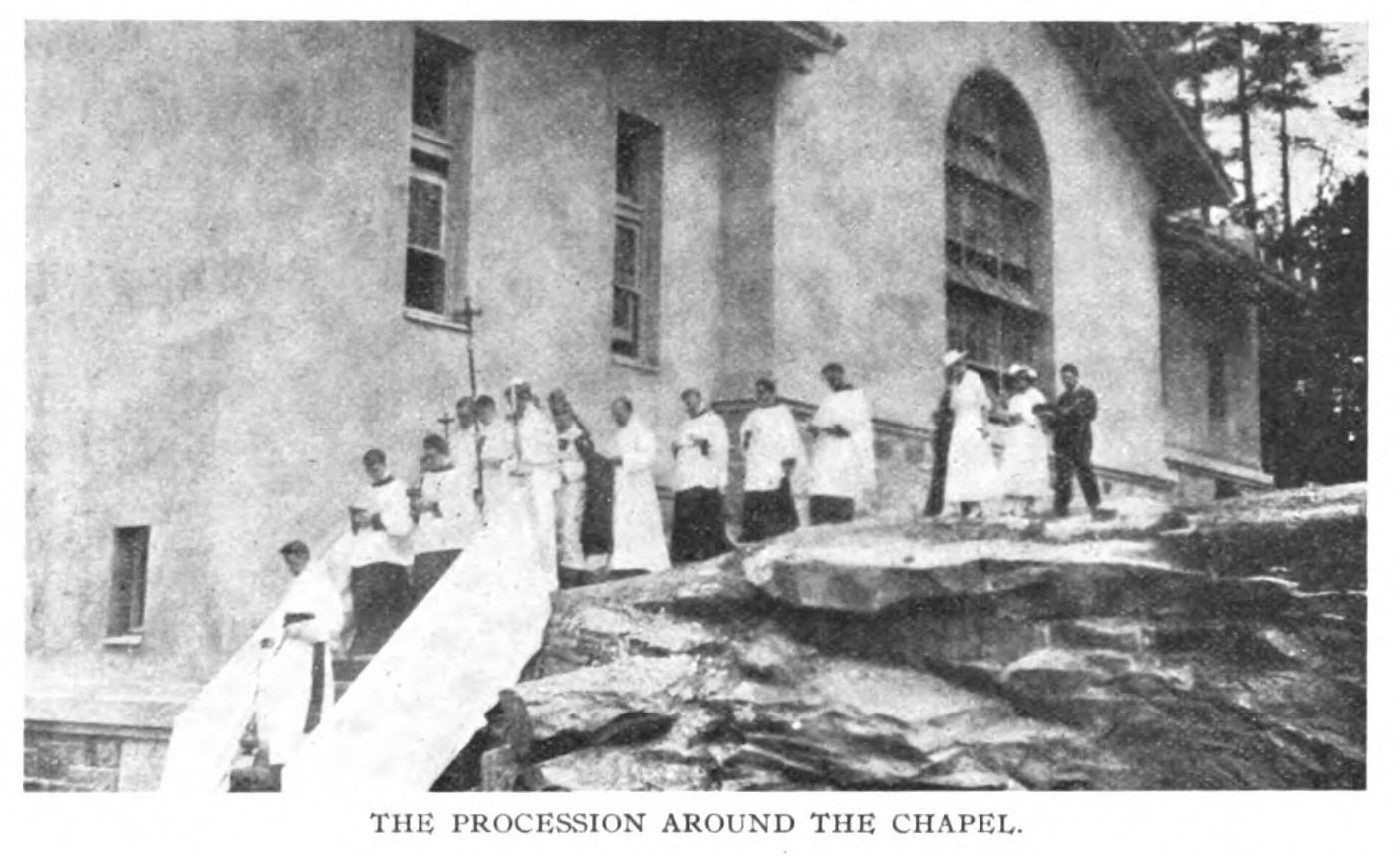

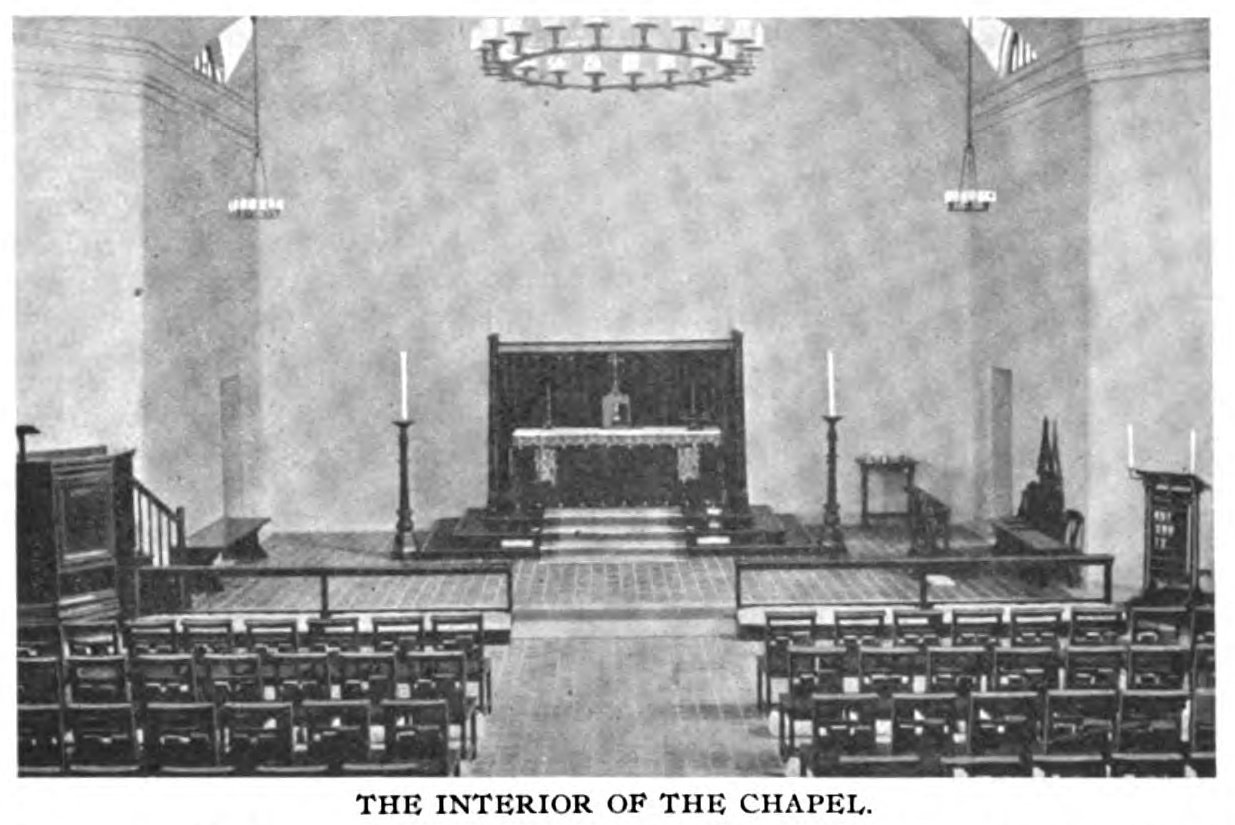

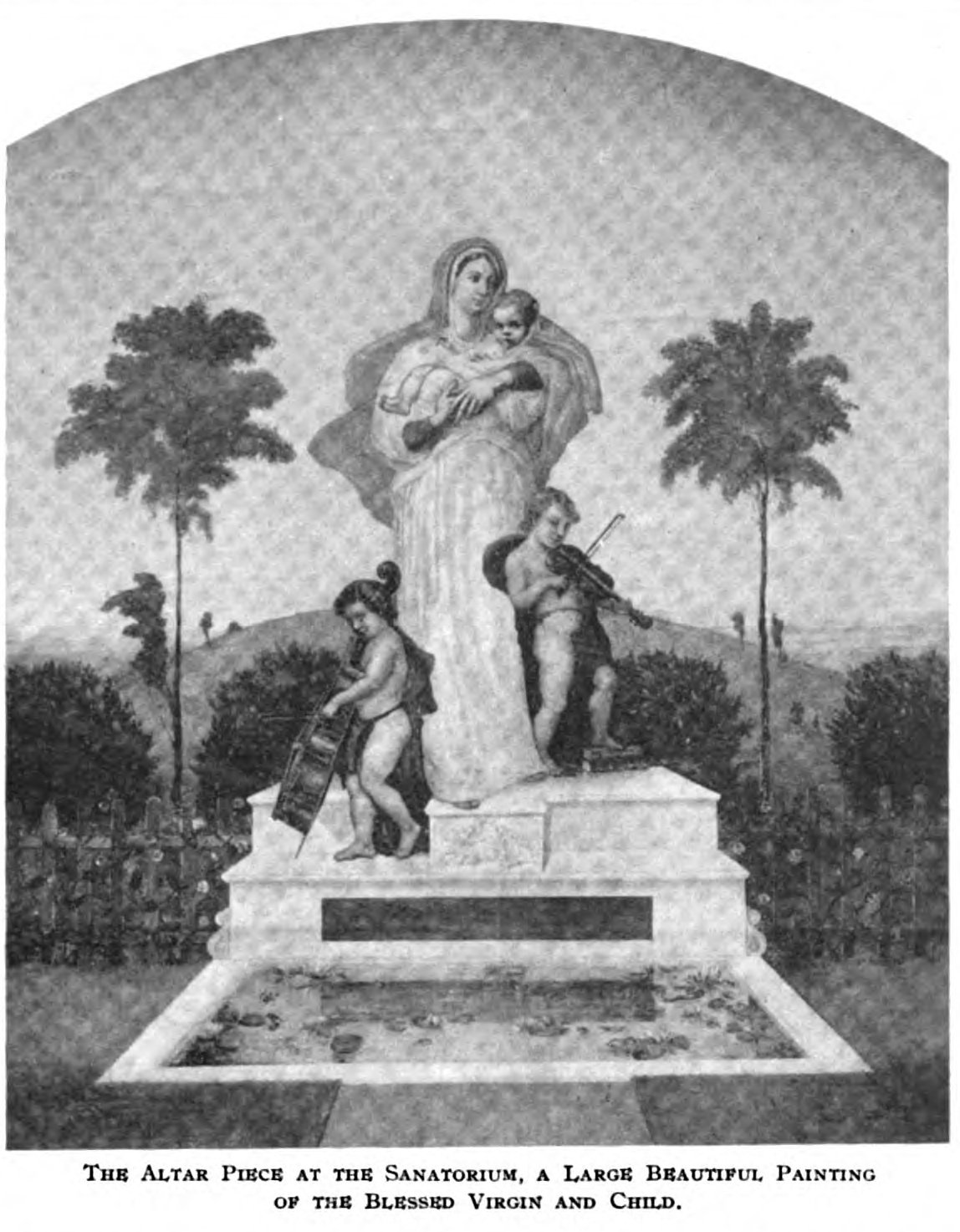

To minister to the community's spiritual needs, St. Mary’s Chapel was built and consecrated on July 25, 1916. The Mission Revival architecture set it apart from the rest of the campus and it featured bells, which would’ve been a familiar sound for many from their hometowns. An enclosed elevated walkway connected the chapel with the adjacent infirmary so that bedridden patients could be wheeled into the balcony to hear sermons. The interior featured a 783-pipe Austin Organ (repaired and listed on the National Register for Historic Pipe Organs in 2006), an ornate 19th-century marble pulpit with brass railings (relocated from the Church of Saint Mary the Virgin in New York City in 1923), and a large altarpiece painting of the Virgin Mary by Elliot Dangerfield. The first sanatorium Chaplain was Italian-born Henry C. Dyer with Henri B.B. Leferre taking over shortly after the opening of St. Mary’s Chapel.

Father Dyer, first Chaplain of the Sanatorium.

The Austin Pipe Organ in St. Mary’s Chapel.

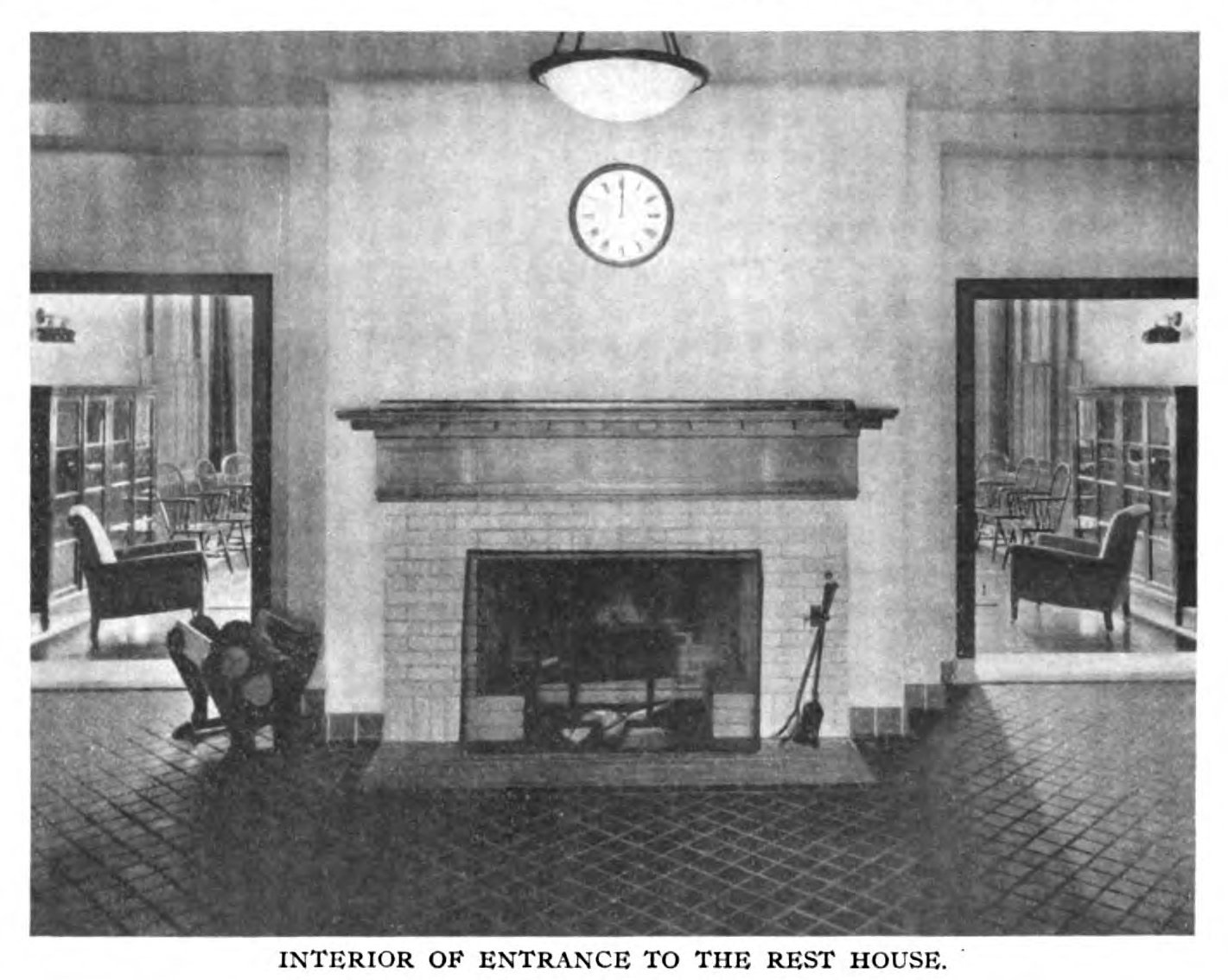

Communal living did come with its risks as evidenced in a small-pox outbreak in December 1914. To help prevent outbreaks of various sorts, the Rest House was opened in 1915 as well as an isolation ward on the roof of the refectory. The Rest House provided accommodations exclusively for non-tubercular patients.

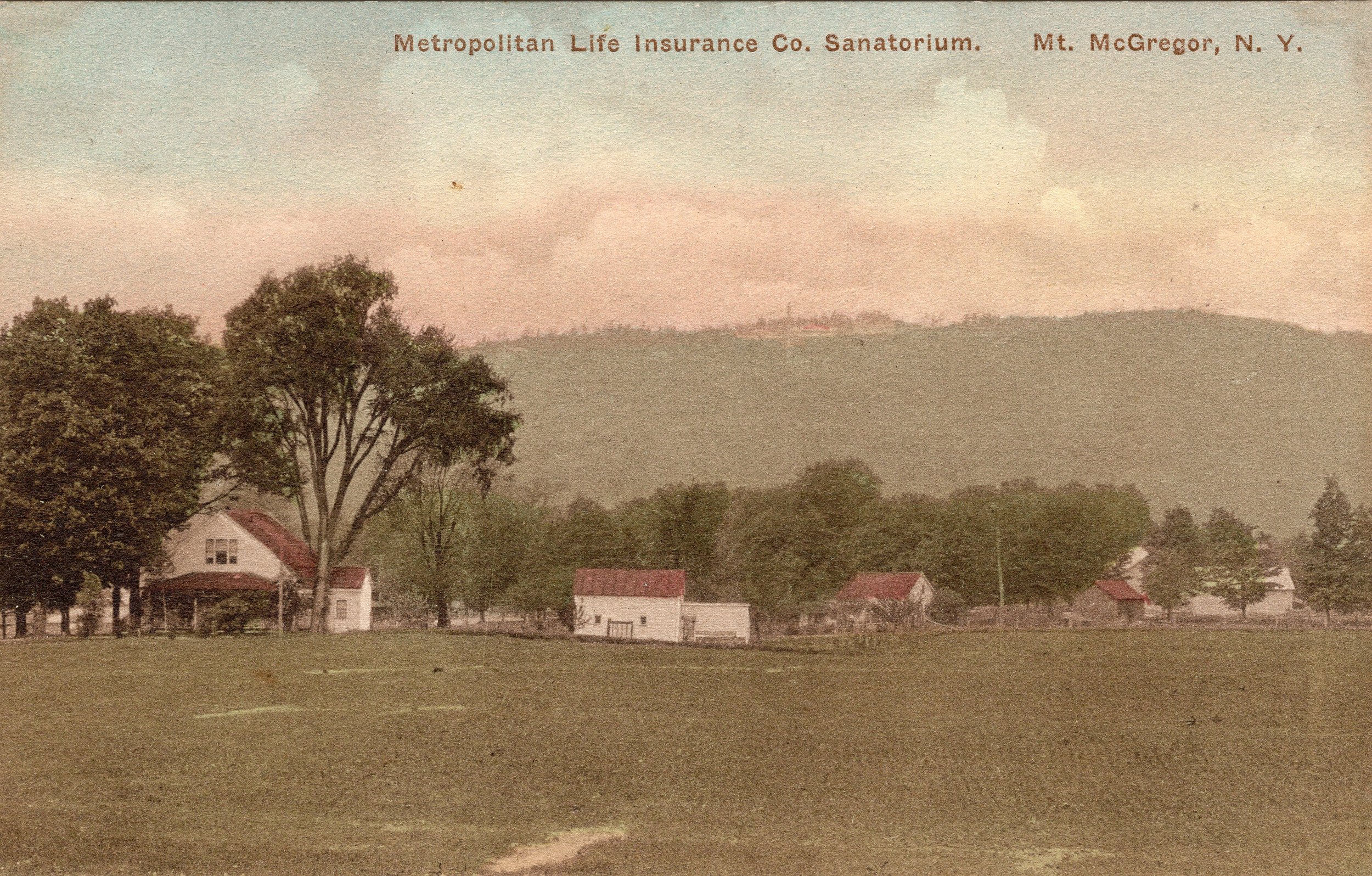

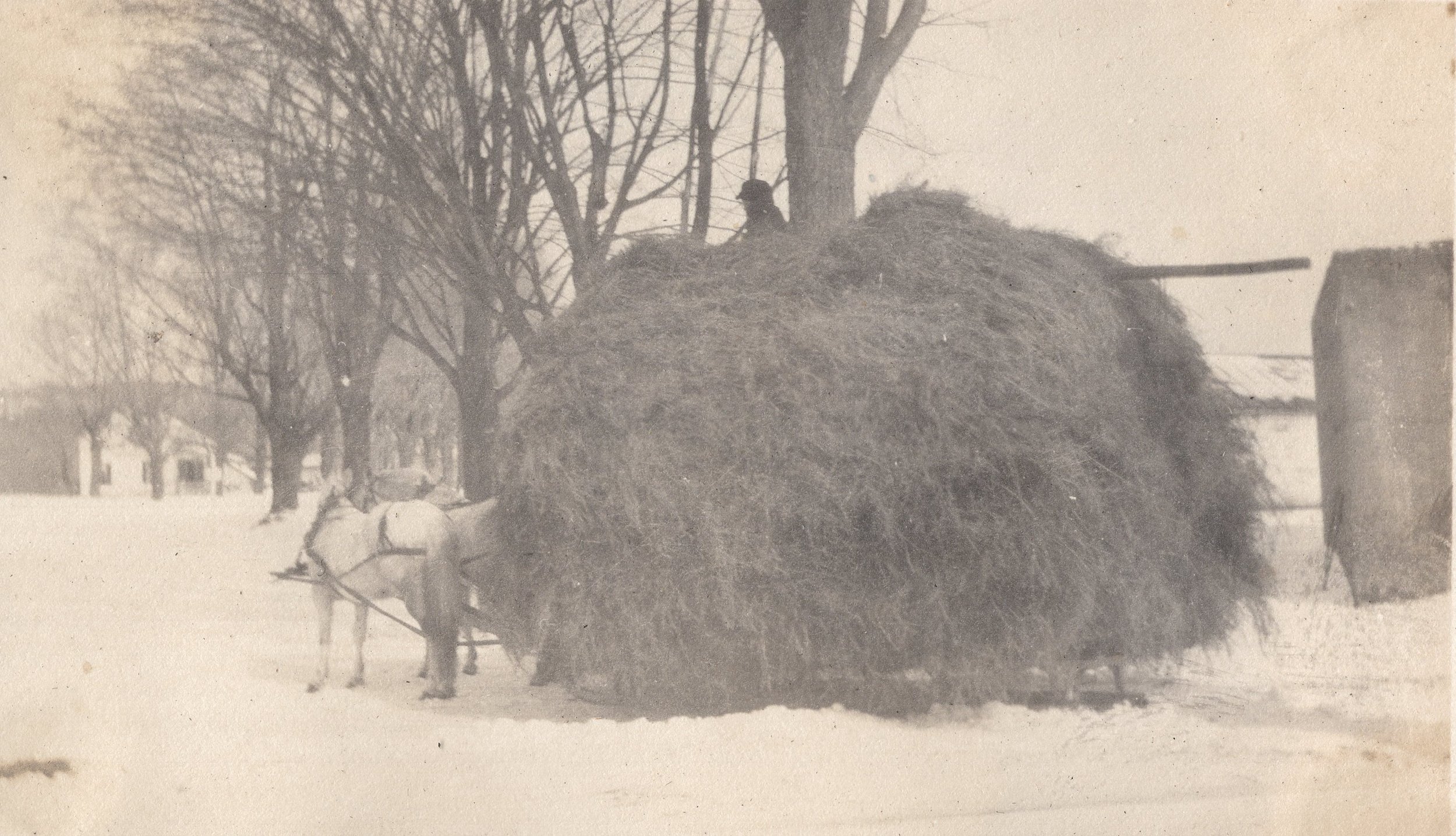

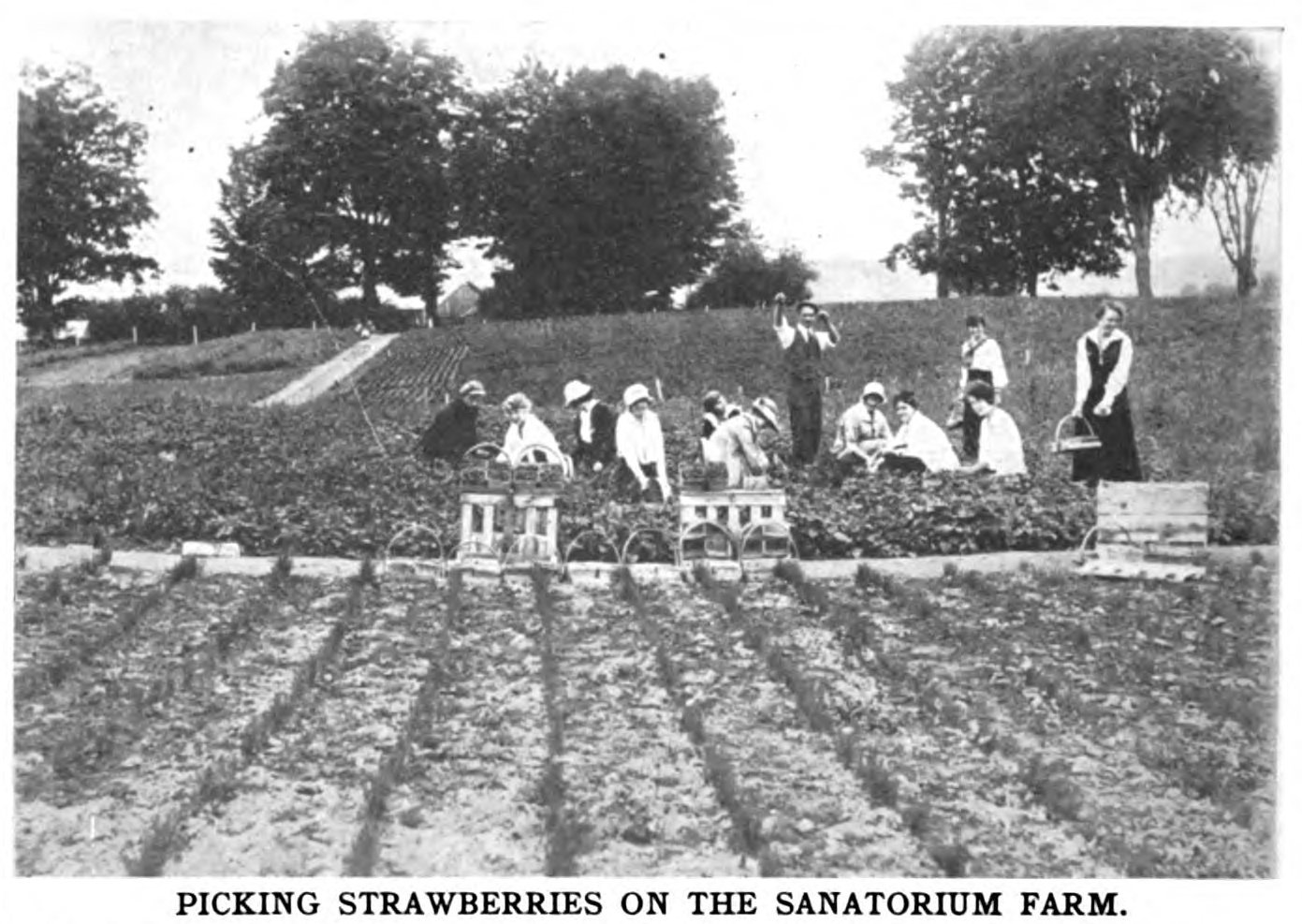

The Metropolitan Farms in the valley were managed by local man William D. Green a holdover from the resort era on Mt. McGregor where he was the winter caretaker of the former Hotel Balmoral. The 540 acres produced vegetables, dairy, poultry, pork, beef and eggs for the hundreds of patients and staff on the mountain. Consideration for the quality of the food was paramount, an example being a herd of Ayrshire cattle supplying more desirable milk.

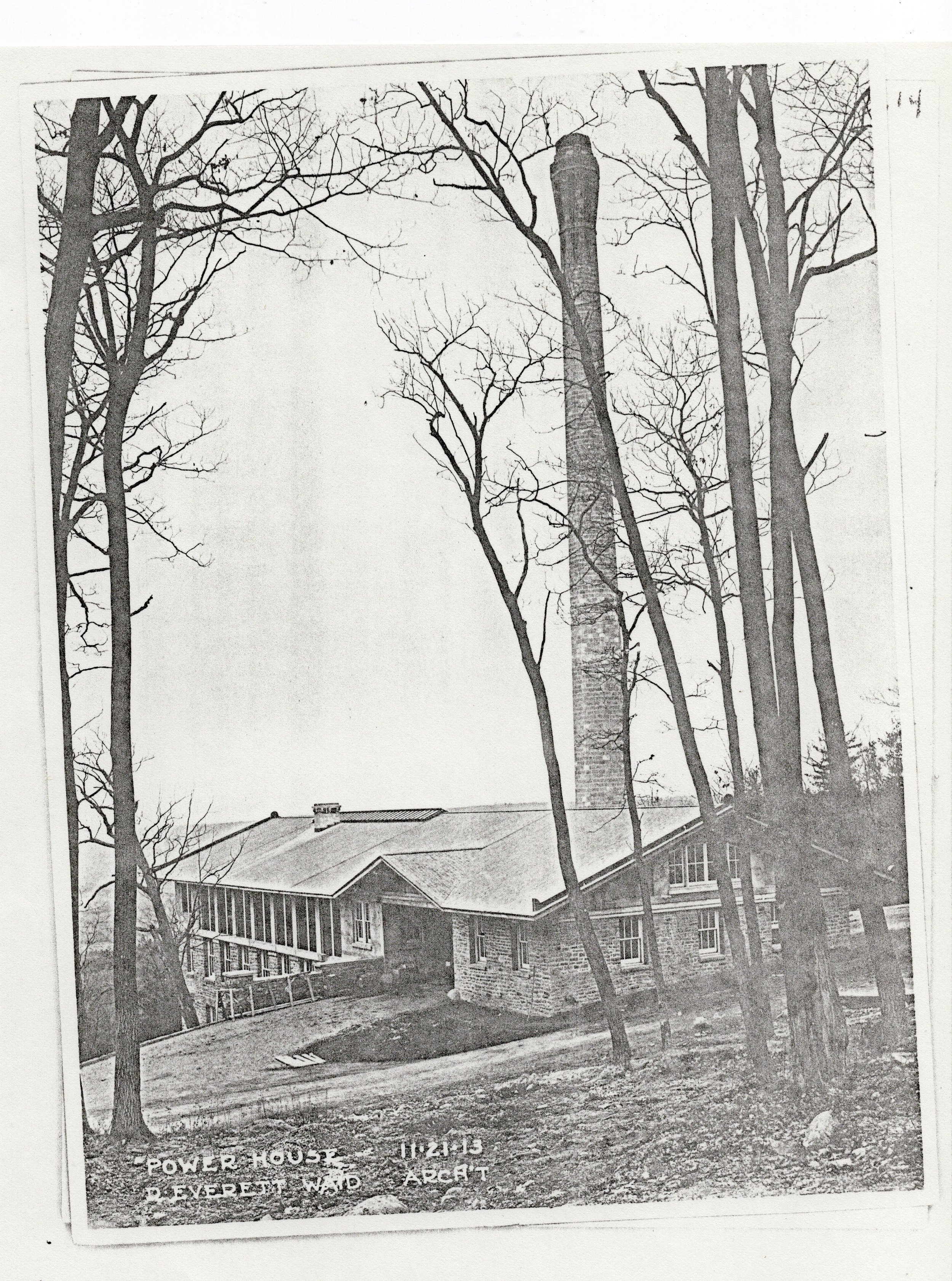

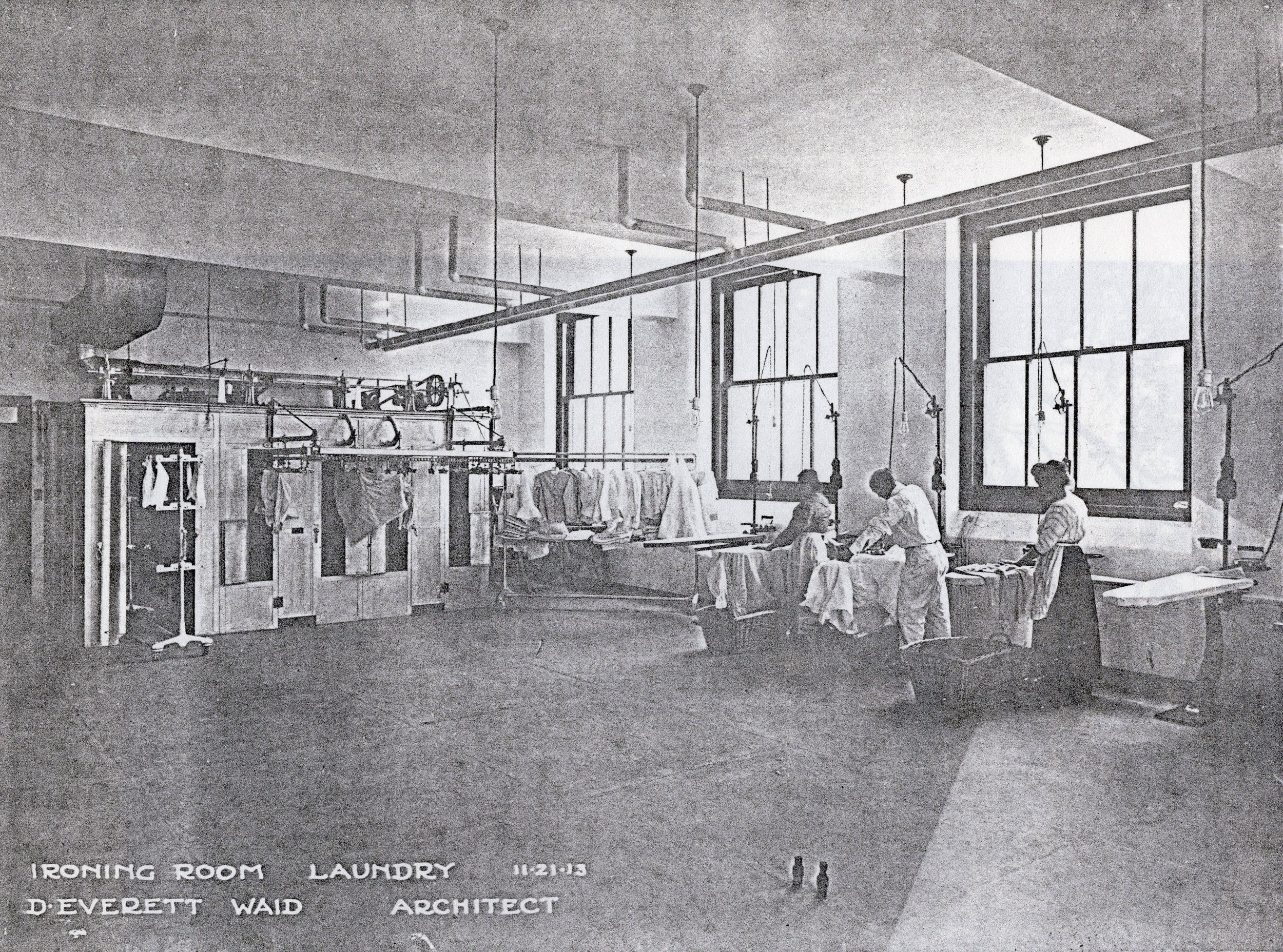

The utility infrastructure had to be impressive to provide for a large community in such a remote location. The heart of the infrastructure was the Power House which served multiple purposes. It served as an electrical hub, waste incinerator, steam heat boiler space, and laundry facility. There was storage for 700 tons of coal to operate the boilers and a 175-foot concrete chimney. A utility tunnel going from the Power House up to the buildings housed the steam pipes, electrical lines, septic lines, water lines, and an “electric railway” for transporting laundry and other materials. It was also tall enough to provide staff with a covered passageway between the main complex and the Power House. Water was piped in by a gasoline engine 3/4 of a mile from Lake Bonita to be stored in a 50,000-gallon concrete water tower. A sewage plant was placed down the hill from the power plant to handle the waste.

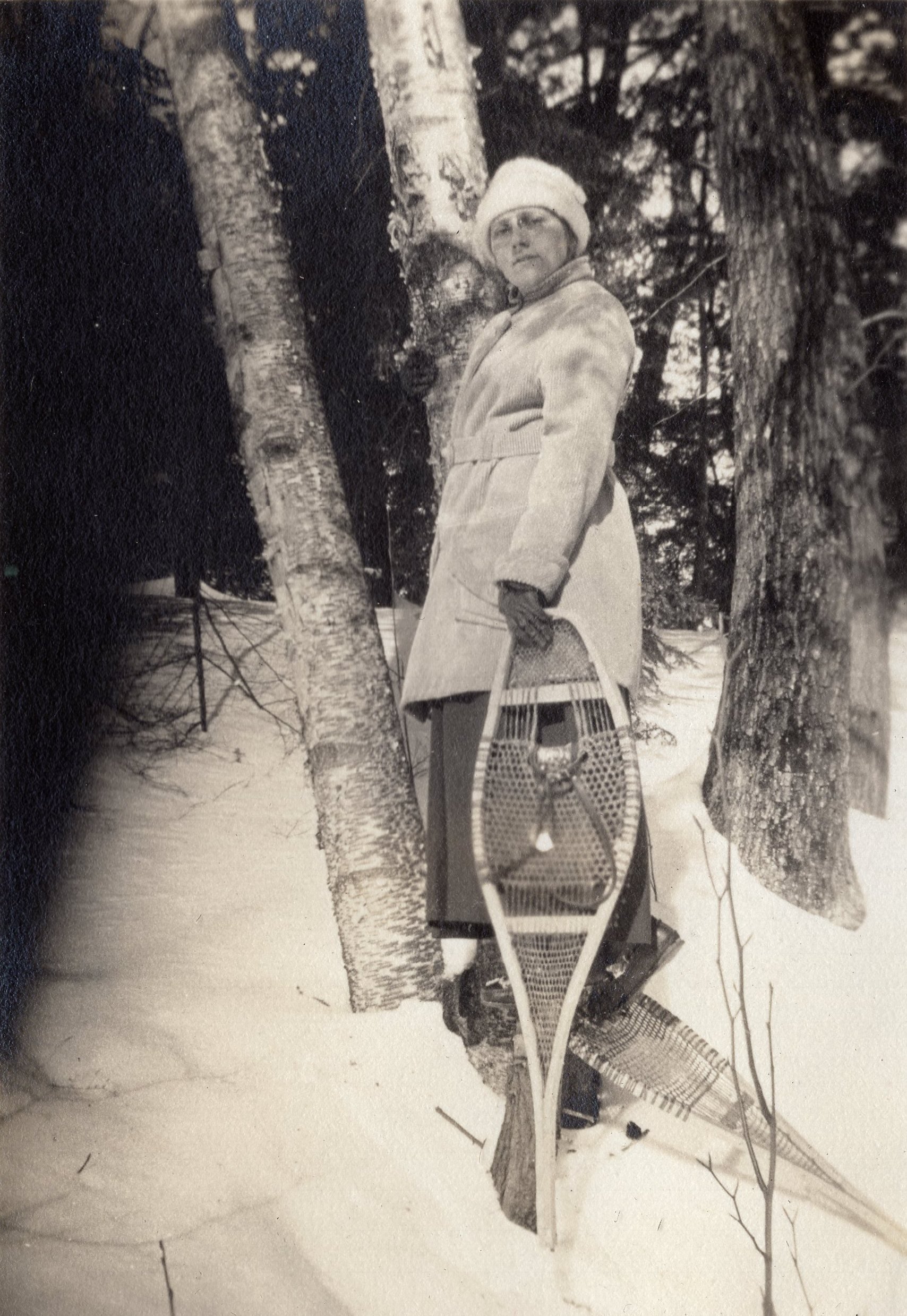

Wintertime on the mountain brought the opportunity for cold weather activities to the patients and staff. Cross country skiing, snow-shoeing, ice skating, tobogganing and sleigh rides were some of the popular pursuits on the mountain. Winter also provided the opportunity to stock up the ice house for the summertime, so ice cutting on Artists Lake was a regular activity before electric refrigeration (500-ton capacity). Just as pleasant as the cooler temperatures and breezes were on the mountain compared to the valley below, the winter could be harsher. During a late winter storm in April 1939 nine inches of snowfall was recorded at the saitorium, while only an inch covered the valley.

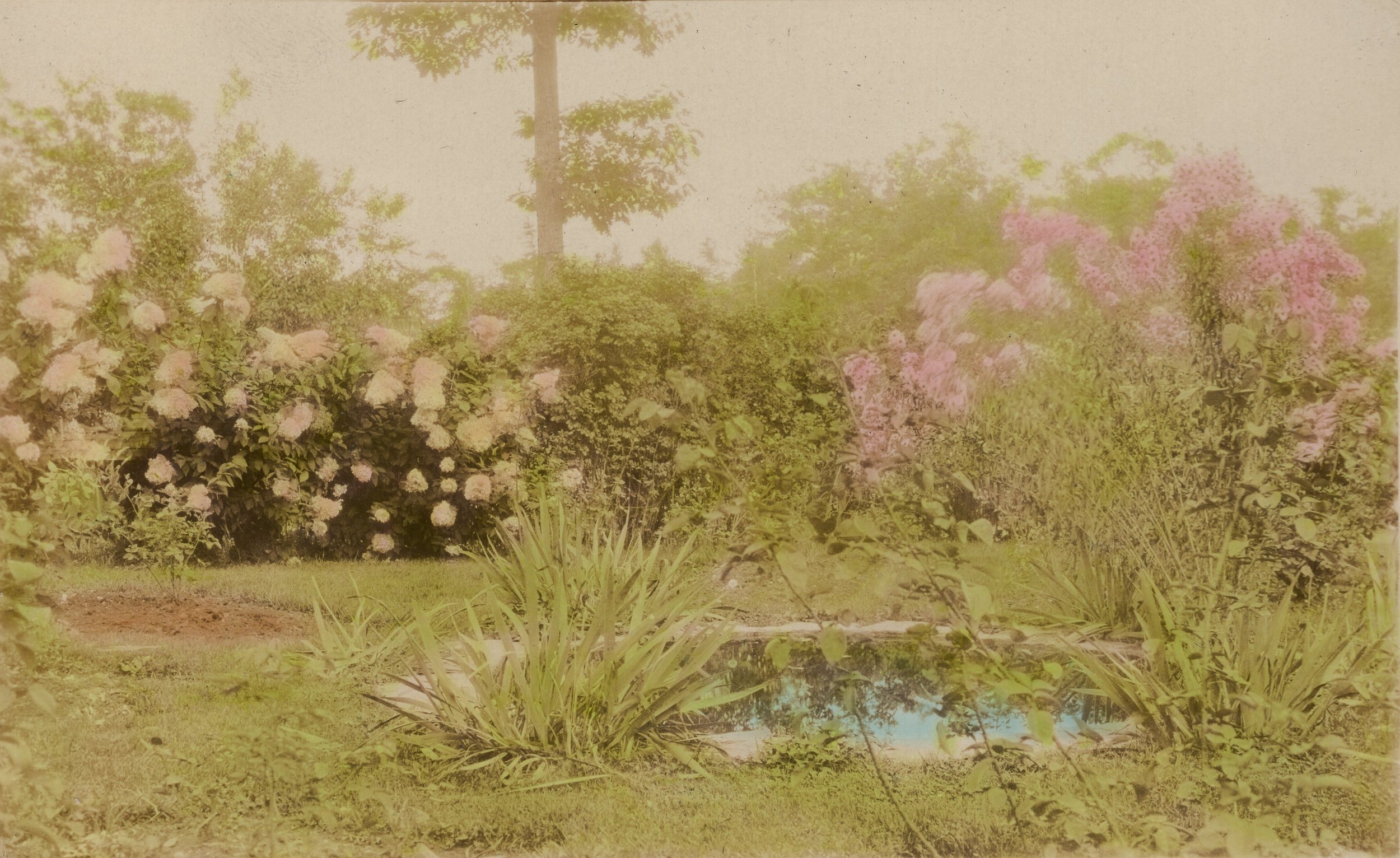

Artists Lake was at the center of the main campus and added greatly to the idyllic setting. Patients and staff gathered on the shores in all seasons and enjoyed swimming, boating and fishing in the summers.

The grounds were very well kept and landscaped with shrubs and gardens. The patients were encouraged to tend their own gardens adjacent to the ward buildings, and to show off their beautiful flowers in contests. The grounds were lit in the evenings by concrete posts topped with a large glass globe containing an electric lightbulb.

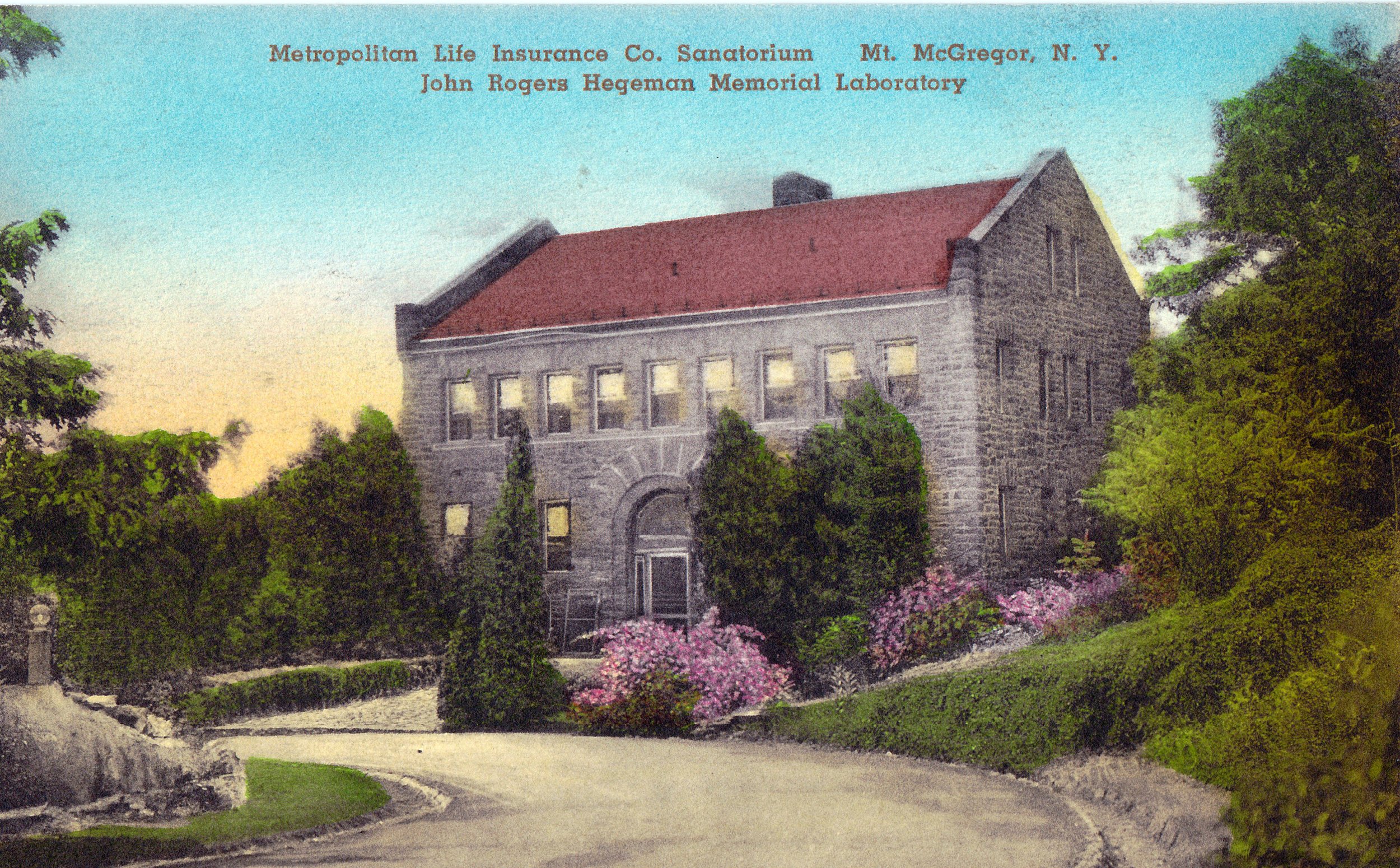

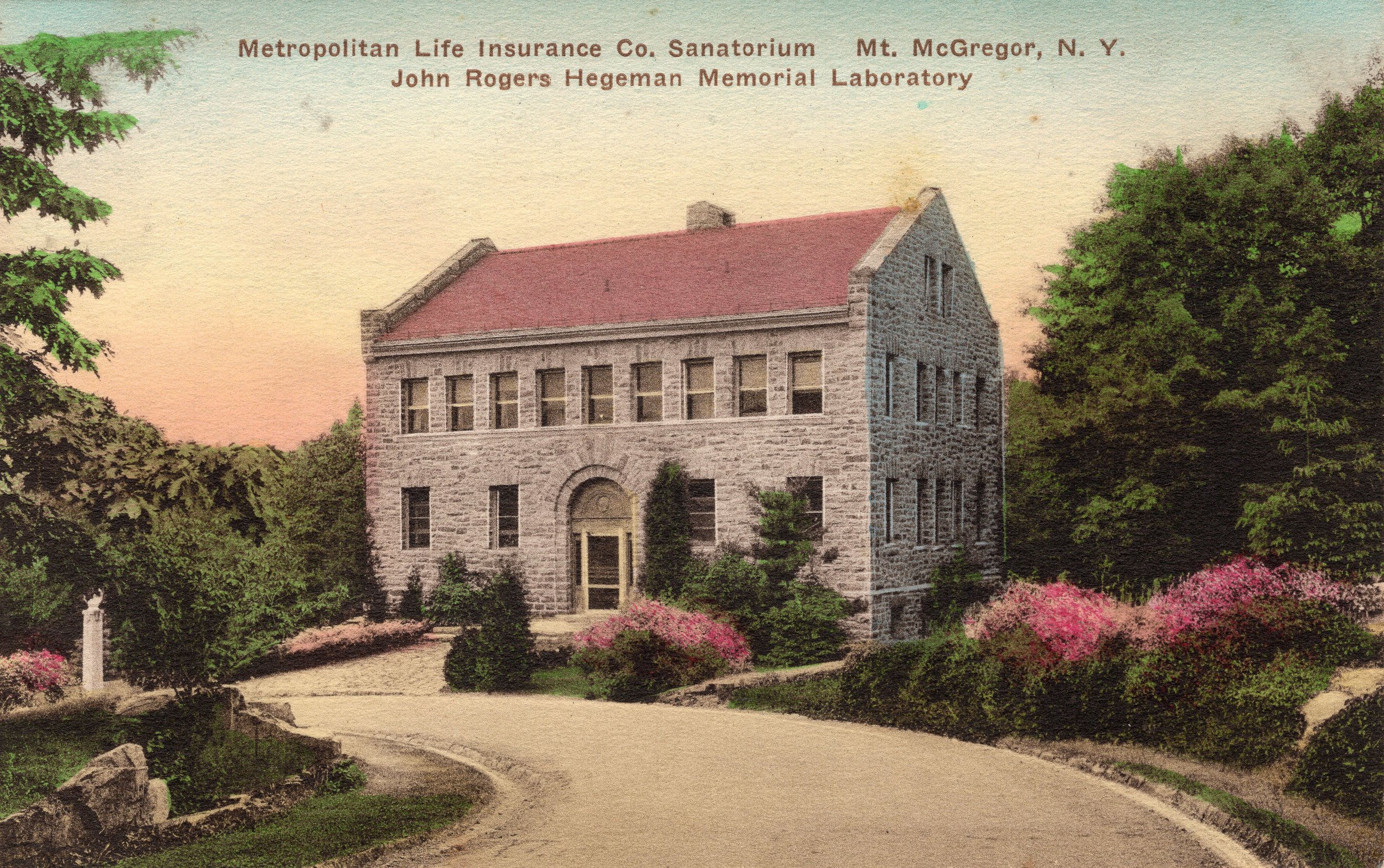

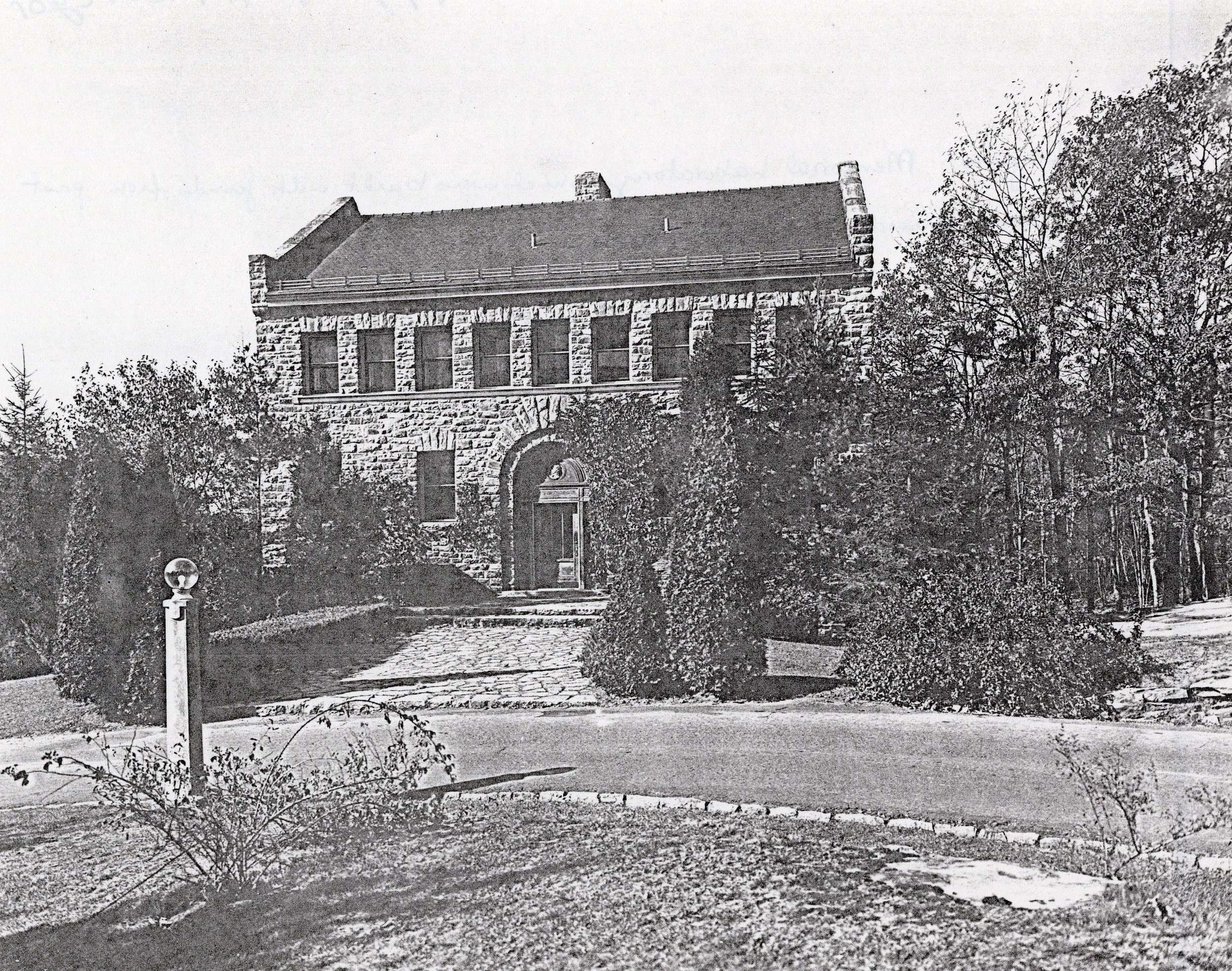

When the president of MetLife John Rogers Hegeman died in 1919, he left in his will directions to contribute a portion of his estate ($300,000) to the erection of a “Hegeman Memorial” building at Mt. McGregor. The company took advantage of this offer to construct the Hegeman Memorial Laboratory for the study of TB and the development of treatments. The dedication of the lab in May 1924 was attended by a large number of prominent physicians including a leading expert on TB, Dr. Edward R. Baldwin. Baldwin contracted TB in the 1890s and sought treatment at Dr. Edward L. Trudeau’s groundbreaking sanatorium in Saranac Lake, NY, later becoming head of the sanatorium after Trudeau died in 1915.

Hegemen at center on Mt. McGregor in 1915.

Brass relief above the entrance the Hegeman Laboratory.

The Hegeman Laboratory is an imposing 50ft x 50ft three-story structure crafted out of granite. The main entrance has a brass door above which is a brass relief featuring a bust of Hegeman. The first story housed the animals used in scientific experiments, their cages suspended from the ceiling for cleanliness. The second story contained rooms for pathology, chemistry, and micro-photography as well as a 100-seat lecture room. The third floor had facilities for bacteriological research including an incubator room. The whole building was supplied with gas, electricity, steam, hot and cold water, compressed air and the most advanced laboratory equipment available.

Dr. Edgar Mathias Medlar (1887-1956)

Dr. Edgar Medlar, a World War I Medical Corps veteran, was appointed director of the laboratory. Under Medlar’s leadership the medical staff published numerous articles and contributed significantly to the research of the disease. In 1954 Medlar was awarded the Edward Livingston Trudeau Medal for “outstanding contributions in the field of tuberculosis.”

Trudeau Medal (Historic Saranac Lake Collection)

Exhibit of Mt. McGregor sanatorium artifacts (Wilton Heritage Society).

The San continued expansion during the 1920s, with a women’s staff dormitory completed in 1928 and culminating in a substantial addition to the Rest House in 1929, with 88 more beds for non-TB patients, making it the largest building on the campus. Dr. Howk recognizing the increase in heart disease cases, had facilitated treatment for over 400 such cases at Mt. McGregor by 1925. Over 50% of those cardiac-related patients were able to return to work and 80% survived. The Rest House provided ample room for various non-TB cases to be treated at the San.

Dr. William Herbert Ordway (1889-1955)

The sanatorium staff and patients were devastated by the loss of Dr. Howk in the early spring of 1926 at only 47 years old. His work left an indelible mark not only on the sanatorium but also on the surrounding region and the advancement of TB treatment. A funeral service was held at St. Mary’s Chapel on Mt. McGregor. The torch of responsibility for the sanatorium was passed to his friend and colleague Dr. William H. Ordway, who had been on the staff for five years. Ordway, who had served as an army medical officer in World War I (attached to the 804th Pioneer Infantry - African American soldiers), would lead the facility for the next 20 years.

“[Dr. Howk] was tender, he was brave, he was kind and possessed of the rare faculty of divining from his own experience how other people felt, and how best they might be consoled. He is no longer with us - but his work goes forward, and he lives in the grateful hearts of those who loved him for himself and for the good he did.”

Christmas Seal featuring Lt. Colonel Dr. Pesquera (1893-1960) in recognition to his work on the Ryukyu Islands of Japan.

Another of the talented and humanitarian members of the medical staff was Dr. Gilberto Pesquera. In addition to his work with early radiology during his 20+ years at Mt. McGregor, Pesquera served in both World Wars, Korea, and traveled internationally on TB-related medical assignments. He was also an advocate for his birthplace of Puerto Rico. Like some other staff and patients, Pesquera found love on the mountain when he wed nurse Lennetta Donovan in 1923. In recognition of his efforts toward eradicating TB, Pesquera was featured on a Christmas Seal, which is a medical fundraising effort of the National Tuberculosis Association (now American Lung Association) originating in 1907.

The San consistently provided the patients with the most modern technology available for medical care but also provided the same in entertainment. In December 1939 the residents of the San experienced a major advancement in digital communications when station W2XB (now WRGB) broadcast a live television program from General Electric studio in Schenectady, NY. The 80-minute program was broadcast to multiple Rotary Club dinners in Schenectady, Albany, Troy, and 40 miles to Mt. McGregor from a transmitter on the Helderberg escarpment. The following May about 50 patients at the San were able to watch the broadcast of the season-opening baseball game between the New York Giants and the Brooklyn Dodgers.

From The Waterbury Democrat 10/24/1939

The success of the fight against TB, and particularly the San on Mt. McGregor, in the early decades of the 20th century were actually the seeds to its demise. In those decades the mortality rate in the United States had been reduced 70%. The Mt. McGregor facility led the way with an impressive 59% of cases being detected in the early stages by the 1930s and most treated successfully at the facility. Despite a vaccine (BCG) being developed for TB in Europe as early as 1921, it was very slow in gaining public acceptance and only saw widespread use after World War II. Early detection and the sanatorium cure remained the standard but with so few Metropolitan employees needing treatment they could now be accommodated at facilities closer to their homes.

The final years of the sanatorium were overshadowed by World War II. The patients supported the war effort as best they could with various fundraising activities. Just days after the war ended in September 1945 (V-J Day) the New York State Division of Veterans Affairs took ownership of the facility. In a final act of generosity and humanity, Met Life sold the property for $400,000, a fraction of its estimated value of $4 million. The San had fulfilled its first mission in its battle against the White Plague and now would embark on a new mission, to provide a place of refuge and recuperation for those who had borne the brunt of military battles.

Stay tuned for the next installment of this series coming soon!

Important Notice: The Mt. McGregor facility property is owned by the New York State Department of Corrections and patrolled by the New York State Police. It is not open to the public. To learn more about the history of Mt. McGregor visit Grant Cottage State Historic Site next to the facility during open hours.

Special thanks to the generous donors of the Crawford, Scoltock, and Clifford photograph collections as well as the Town of Wilton Historians office and the Wilton Heritage Society.

Sources:

The Daily Saratogian, 8/13/1903

Mechanicville Saturday Mercury, 11/14/1908, 12/31/1910

The Cohoes Republican, 8/20/1909

The North Westchester Times, 11/25/1910

The Fort Edward Advertiser, 1/19/1911

The Post-Star, 1/18/1912, 2/2/1912, 8/13/1912, 6/10/1913, 6/22/1914, 3/16/1915, 3/5/1928

The Saratogian 5/15/1912, 6/20/1914, 11/25/1918, 7/26/1923, 4/3/1939, 4/2/1955

The Intelligencer, Vol. 8, Num. 11, 7/11/1914

The Sun (New York), 7/18/1915

The Amsterdam Evening Recorder, 6/28/1919

The Newark-Union Gazette, 8/9/1919

The Evening Express (Portland, ME), 6/18/1925

The Greenwich Journal and Fort Edward Advertiser, 5/5/1926

The Silver Creek [NY] News, 7/5/1934

The Waterbury Democrat 10/24/1939

The Glens Falls Times, 2/24/1931, 12/7/1939, 9/29/1945

The Sydney Morning Herald, 5/22/1940

The Tupper Lake Free Press and Tupper Lake Herald, 7/5/1956

The Intelligencer Volumes 1-

The Story of St. Mary’s: The Society of the Free Church of St. Mary the Virgin New York City 1868-1931 (1931)

Mt. McGregor Optimist, Vol. 15, Num. 5, April 1932

Early Television Museum website: https://www.earlytelevision.org/w2xb.html