““E’en do bait spair nocht.”

“In what you do, spare nothing.””

Arkell’s Ambition

On September 20, 1881, almost nine years to the date of the opening of the mountain, a bold and ambitious new vision for Mt. McGregor would emerge. As the nation, including Ulysses S. Grant, sadly bade farewell to President Garfield after the second shocking assassination in less than 17 years, a group of wealthy businessmen would become enchanted with Mt. McGregor’s charms and see in it boundless potential. Leading an excursion group would be prominent businessman James Arkell and his 25-year-old son William James, known as “W.J.,” from Canajoharie in New York’s Mohawk Valley. The Arkells had made a fortune during the Civil War by producing paper sacks when cotton was scarce and expensive. W.J. recounted that after a long carriage journey, the group stood on Mt. McGregor and their associate John Kellogg, a linseed oil producer from Amsterdam, NY, turned to him and asked “W.J., why don’t you build a railroad to this beautiful spot?” W. J. countered Kellogg asking him how much he would contribute. Caught up in the moment Kellogg pledged $25,000 ($720,000 in 2022) and so did W.J.’s father with W.J. making it an even $100,000. It’s likely Kellogg and the others were inspired by the construction of the nearby Saratoga Lake Railroad just the year before, connecting visitors of the resort town of Saratoga Springs with one of its most popular excursion locations.

William J. Arkell (1856-1930)

John Kellogg (1826-1911)

Things moved ahead very rapidly. Articles of Incorporation for The Saratoga and Mount McGregor Railway Company (later named Saratoga, Mt. McGregor, and Lake George Railroad) were submitted less than two months after the mountaintop meeting. Kellogg was named President and W.J. the Vice President of the venture. At the same time plans were being developed to expand lodging and dining facilities on the mountain and The Mount McGregor Improvement Company Limited was incorporated soon after. The mountain, especially the “field of dreams,” was set for a dramatic transformation over the next few years.

1882 Advertisement for work on the Mt. McGregor Railroad

The first ambitious stage of expansion was to build a narrow-gauge railroad about 10 miles from Saratoga Springs to Mount McGregor. With a climb of over 700 feet in elevation, mostly in the last few miles, this was never going to be an easy task but was sure to draw more visitors to the mountain with a faster, easier commute. A newspaper article stated that with a railroad the mountain “will add very greatly to the attractiveness of Saratoga Springs” and that the resort “only needs developing to become more popular than it is already.” The hopeful W.J. stated that “if the road can induce 60,000 of the 150,000 annual visitors to Saratoga to ride over this road, its success is certain.” Work began in earnest on the new venture with John McGee, an engineering expert who had worked on rail projects in the Andes Mountains, overseeing the project. An incredible timetable was put forth looking to have the route operational by early summer 1882 and scores of workers were brought on for the difficult labor. In trying to make the project state of the art, there was even talk of having Thomas Edison’s new electric locomotive in use on the line (incidentally in 1883 inventor Leo Daft would test his electric locomotive Ampere on the Mt. McGregor line). In the end, the railway settled for the use of the standard steam engine technology.

James Arkell (1829-1902)

After an astonishingly short period of only four months of rock blasting, culvert and bridge construction, and track laying, the railroad was ready for service by July 17th, 1882. To celebrate the occasion hundreds boarded the new railroad cars bound for the mountain. Upon arrival, the guests gathered on a temporary platform in the field of dreams where speeches were given and music performed by a 22-piece band. Speakers included George Batcheller, who had spoken ten years before at the opening of the carriage road and had since been appointed by President Grant as an international judge in Egypt. Speakers including W.J.’s father James Arkell and fellow politician Charles Hughes, extolled the efforts of the financiers, designer, and workers that brought the ambitious project to completion. In speaking of the enterprise, Hughes evoked the traditional motto of the Scottish Clan McGregor, “'E'en do bait spair nocht” which translates to “In what you do, spare nothing.”

The Side of Mt. McGregor (ca.1885) by Andrew Melrose (1836-1901)

“The wild and magnificent scenery along the mountain [rail]road can not be described. It must be seen to be appreciated. You are constantly startled with the sudden changes. Every turn is a surprise. All the senses and emotions are called into play in an incredibly short time. Now your poetic soul is fired with a fifty mile landscape spread out before you, but your ecstasy is suddenly broken, as the train dashes through a rocky cut, and scarcely has the cavernous roar died away before you are gazing timidly from some giddy trestle into a yawning chasm... and in a moment we are seemingly buried in a primeval forest. We soon emerge, and as we near the top we see through extended vistas into broad valleys below, and over boundless landscapes beyond. ”

The Grotto on Mt. McGregor from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper (1882)

Lake Anna from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper (1882)

The allure of the wilderness was taking a new form as the resort on Mt. Mcgregor was being re-imagined. Not only was it a place of escape from the busyness of city life, but an increasing desire to preserve the forests was becoming tied into it as well. Surveyor Verplanck Colvin was actively lobbying for the protection of the forests of the Adirondack region of which Mt. McGregor is a part. The natural features of the mountain, the tall shady pines and majestic oaks, pristine waters, flora, and fauna were frequently featured in advertisements. This emerging conservationist idea is expressed in a newspaper article about Mt. McGregor stating that “enterprises of this character will go far toward protecting from destruction the natural beauty and attractions of our many lovely mountain resorts.” As the resort grew the original goal of not allowing improvements “to interfere with the natural wildness of the scene” so that “all the charms of the wild woods are carefully preserved” remained. This theme of preserving the natural character of the mountain would be repeated in future years.

View from the Western Outlook from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper (1882)

Oscar Wilde (1854-1900)

Visitation to the mountain increased dramatically with the opening of the railroad. Notable visitors in the summer of 1882 included 27-year-old Irish poet and playwright Oscar Wilde who gave a lecture on aesthetic decorative arts in Saratoga Springs. Wilde attended a breakfast at the Overlook Restaurant on Mt. McGregor with notable individuals including Judge Arthur MacArthur Sr. (grandfather of Douglas MacArthur) and U.S. Senator William Everts (former U.S. Secretary of State). After an amusing introduction by humorist Melville Landon (pen name “Eli Perkins”), Wilde commented fondly on the aesthetics of the mountain, “If there is anything more necessary than a good income, it is to have beautiful surroundings, and we have here today just the loveliest that could be, beautiful trees, beautiful landscapes, and above all beautiful women.” The Governor of New York Alonzo B. Cornell, who had served in the Grant administration, visited the mountain and was so impressed that he reportedly spoke for rooms at the planned hotel. Ex-president Ulysses S. Grant visited Saratoga Springs in August, as he had done multiple times after the war, and was likely aware of Mt. McGregor as its development was the talk of the town at the time. During the season it was estimated that some 10-15,000 people visited the mountain using the four trains of 2-3 cars each daily at the $1.00 round trip fare. After ten years of use, the carriage road up the mountain was also updated to handle those arriving the “old-fashioned” way.

Map from Mt. McGregor, the Popular Summer Sanitarium, Forty Minutes from Saratoga Springs (1884)

Image showing structure believed to be the Overlook Restaurant on Mt. McGregor. From a Seneca R. Stoddard steroview.

While plans were being drawn up for a luxury hotel on the mountain, the developers knowing that they would have to compete with world-class resorts in Saratoga Springs, made sure their plans included the latest technologies. Electric lighting was installed at Mt. McGregor by inventor Clinton M. Ball of Troy, New York who had patented electrical lighting circuits in 1880. Ball installed a generator and seven lamps on the property, one of which was installed at the top of a newly constructed 72ft high windmill-powered artesian well/observation tower which could be seen up to 25 miles away. The Overlook Restaurant was described as a “long, one-story dining room” that was built in the “Manhattan Beach style, with windows extending to the floor, easily opened or closed as occasion demands… [and] A wide piazza extends on three sides of the Restaurant affording ample opportunity to enjoy the scenery and cool breezes.” Meals were offered to diners for $1.00 and up. The problem of ample guest accommodations had to be solved temporarily as well. The solution was the 19th-century version of what is now referred to as “glamping” being created on the grounds of the resort. A multitude of wall tents created a campground offering a rustic and romantic experience where “the most delightful of sleeping accommodations are offered. Few will willingly go back to a housed bedroom, after a night under canvas.” There were even unfulfilled rumors of offering resort guests exotic elephantine chariot rides to Lake Bonita in the following year.

Illustration of the artesian well & campground on Mt. McGregor from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper (1882)

1882 Advertisement

As 1883 dawned on the mountain a new investor came onto the scene, Joseph Drexel. Drexel, a wealthy banker from Philadelphia who maintained a summer home in Saratoga Springs, became interested in the developments occurring on the mountain the previous year. In February, W.J. purchased most of the land from Duncan McGregor for $50,000, and the directors, now including Drexel, were given the legal green light to further develop the resort. The developers had tapped 28-year-old burgeoning architect, Albert W. Fuller of Albany, New York, to put their vision on paper. The plan included features “to make the hotel equal to those of Long Branch [NJ] and Saratoga.” In early April the construction firm of Stanton & Neary began blasting the bedrock in the “field of dreams” to make way for the foundation of the new hotel with hopes of completing the building in time for the summer season.

In May one of the great dangers to the mountain enterprise, and to forests of the Adirondacks in general, was demonstrated when sparks from the train started a wildfire. Being in a remote location with limited firefighting methods represented an ever-present concern for the resort developers. Over the years a number of fires had threatened the resort and a couple of buildings were lost. Designs for the new hotel would incorporate some fire protection utilizing the nearby pond (Artists Lake) as a water source.

When he was younger W.J. had narrowly survived a terrible explosion and fire at his father’s mill. He battled with recovery from the extensive disfiguring burns to his hands and face for a long time afterward. This traumatic life-threatening incident may have contributed to the ambitions that would fuel the future of the mountain resort. Regardless of the source of his zeal, people were taking notice of the intrepid young man from the Mohawk Valley:

“From the start Mr. [W.J.] Arkell has been the mainspring of the Mount McGregor enterprise, personally directing all movements of organization and construction, as vice president of the company…. he has practical skill, as well as faith and "pluck… Mr. Arkell has only recently passed his twenty-sixth birthday anniversary, and has an honest pride in being the youngest railway manager in the United States. He is full of enthusiasm over his new venture, which seems as certain to be successful as any enterprise can be which depends on the public for its support. He is a true type of Young America, of the class who are placing this country in the front rank of great enterprises.” -The Glens Falls Times (1883)

The intrepid entrepreneur and his wife Minnie, the daughter of Irish immigrants, were raising their two young children, James and Margherita, as the resort was being developed. The Arkell family’s giant English Mastiff “Major” was a fixture on the mountain and proved a favorite with resort guests. W.J. was characterized as inheriting “all his father's business and financial tact.” He was described as a “short, thick, heavy-set man [with] a massive head, and an expression about his face that indicates shrewd business judgment and strong willpower. He is exceedingly affable, and is a good storyteller.” The historical record indicates his “stories” were certainly liable to be significantly embellished at times. “Ambitious Billy,” as one paper called W.J., was apparently also quite adventurous. It was reported that after the railroad fully opened in June, W.J. and artist Harry Fenn survived a perilous hand-car ride down the mountain tracks. The two men reached a great speed and the brakes failed causing W.J. to be thrown off getting bruised up with Fenn clinging to the cart until it reached the bottom. In addition to steam yacht racing in Long Island Sound, later in his life, W.J. would admit to recklessly racing early automobiles. He not only took big risks with his investments but also on horse races.

Resort guests enjoying the view from the ‘field of dreams” on Mt. McGregor.

W.J. also had a penchant for art that he brought to the mountain. A year before coming to Mt. McGregor W.J. guided the professional artists of the Artists’ Fund Society on a journey by canal boat along the Erie Canal, stopping to allow them to capture the beautiful scenes along the way. The artists thanked him with a collection of art with an estimated worth of $20,000 ($585,000 in 2022) and his brother Bartlett would later open the Arkell Museum in Canajoharie, NY.

The Mt. McGregor Art Association was formed to bring urban sophistication to the wilderness. Architect Fuller designed a Queen Anne-style art gallery building on Mt. McGregor to house 105 oil paintings in one gallery with 13 watercolors and 36 etchings in another for the 1883 season. Willard Finehout, one of the numerous individuals associated with the Arkells and the Canajoharie, NY area, was chosen to run the gallery. The building sat on the picturesque shore of a small pond appropriately christened Artists Lake. The charming gallery reached by a woods path proved popular with the cultured and wealthy summer visitors that flocked to the mountain that summer. An admission fee allowed visitors to view works by prominent American artists such as Albert Bierstadt’s The Rocky Mountains and Thomas Moran’s Hiawatha with $9700 ($285,000 in 2022) worth of art sold before the season ended. It is interesting to note that Finehout, a manager of early baseball clubs, worked only about a hundred yards from the “field of dreams.”

The Art Gallery as depicted in Harpers Weekly (July 14, 1883)

John Whetten Ehninger (1827-1889)

Turkey Shoot oil painting by John Whetten Ehninger was one of the works displayed at the Art Gallery on Mt. McGregor in 1883.

It was not just those interested in the arts but also the sciences that were drawn to the mountain. The resort remained a popular excursion point for the various organizations gathering in nearby Saratoga Springs. In June 1883 a field day meeting of the Dana Natural History Society of Albany was conducted on Mt. Mcgregor. The society held the rare distinction of its membership being exclusively females associated with the Albany Female Academy. They enjoyed exploring the natural history and views of the mountain before gathering for a picnic and speeches on the plateau in front of the hotel still under construction. As far as visitors to the “field of dreams” with an eye to the future, these women were at the forefront of transforming women’s traditional roles in society.

1883 Advertisement from the Daily Saratogian.

Advertisements for Mt. McGregor increased and took various forms as they spread to national papers. Some were flattering accounts by visitors and standard newspaper ads while others were fictional tales of adventure meant to entertain and entice. The advertisements included brochures and booklets with alluring imagery. As a means of enticement, reports of scouting and clearing lots for the building of private cottages claimed about twenty interested investors but no evidence exists that these ever came to be. The resort was certainly growing though, attracting over 23,000 guests during the 1883 season.

1883 Mount McGregor Advertisement

Advertisement from The Daily Saratogian - August 1883

Many would find their dreams of love and romance coming true on the mountain. Bridal parties, couples in courtship strolling or picnicking, and moonlight train excursions featuring starlight skies and the magic glow of electric lights all added to the alluring reputation of the mountain. A claim was made that 22 bridal couples visited the mountain on a single day in July 1883.

““This evening the Mount McGregor railroad company will run an excursion train up the mountain to give all lovers of nature an opportunity to enjoy the magnificent outlook from its airy summit under the attractive and bewitching light of a bright full moon. The trip will be new, novel and unique and furnish a strikingly agreeable way of passing a delightful evening. The view will be one which none should miss seeing. It will be both romantic and grand.””

The cottage in its new location southeast of the hotel.

It is important to recognize the sheer physical stamina and effort that went into turning dreams into reality in the late 19th century as well as the risks involved. Hundreds of workers, many of them immigrants, made the mountain railroad materialize with only a few recorded accidents, none fatal. One of the dozens of workmen employed on the new hotel in the summer of 1883, carpenter Harry Maynard, fell from scaffolding 30 feet to the ground but was very fortunate to walk away with nothing but severe bruises. In October train loads of glass, sand and plaster were arriving on the mountain awaiting the workman’s skilled hands. Indicative of the unique climate on the mountain, snow showers were reported as early as mid-October. By November the final touches were being completed on the new hotel and it was time to move the old resort buildings from in front of it to their new locations. One of those buildings, a two-story cottage, was moved to the southeast a few hundred yards and would be fated to play a major role in the history of the mountain and the nation.

““The new hotel being built on Mount McGregor looms up far above the tree tops so that it can be seen for miles around.” ”

Image of Mt. McGregor showing the Hotel Balmoral from Seven mile funeral cortège of Genl. Grant in New York Aug. 8, 1885 by the U.S. Instantaneous Photographic Co.

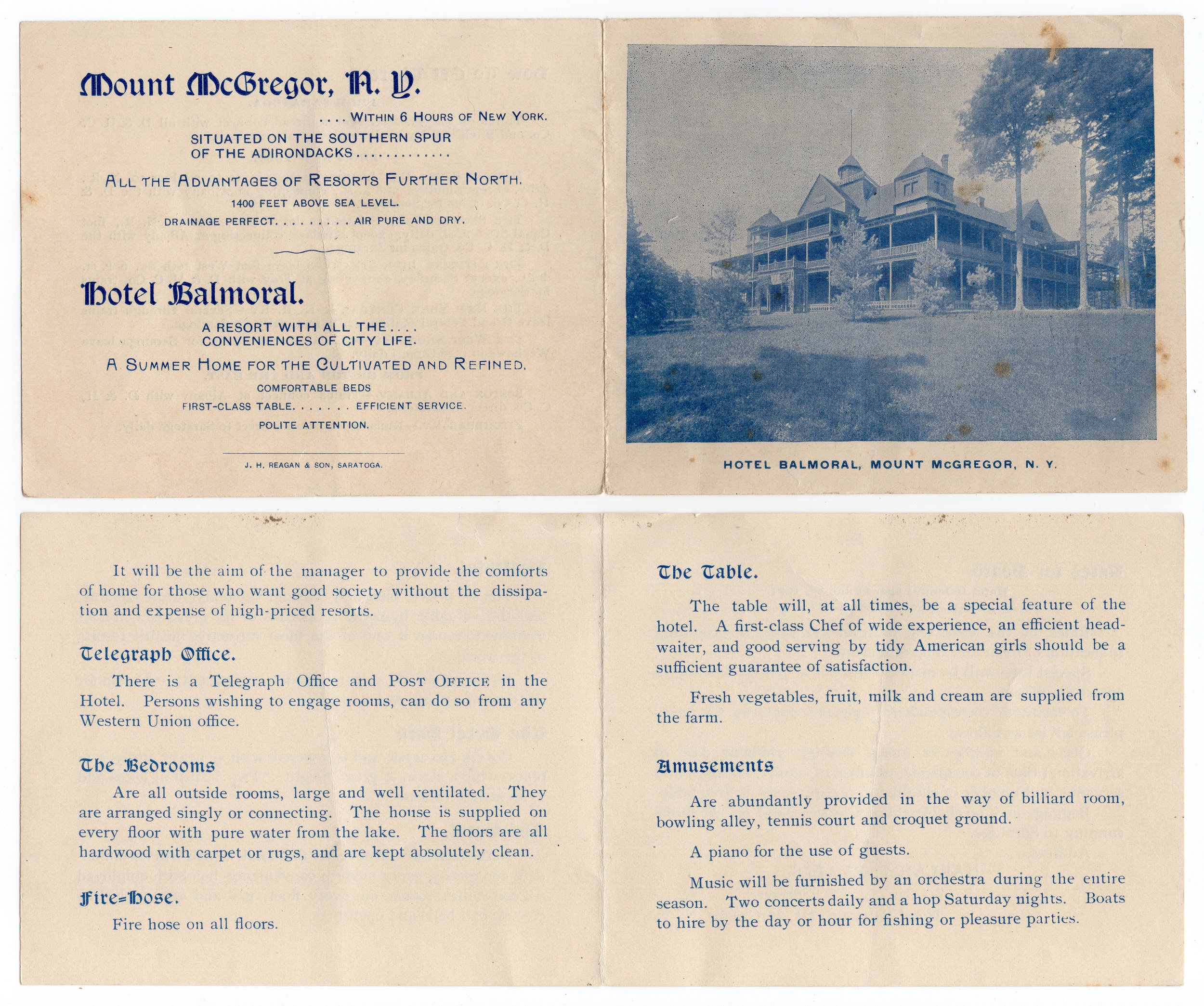

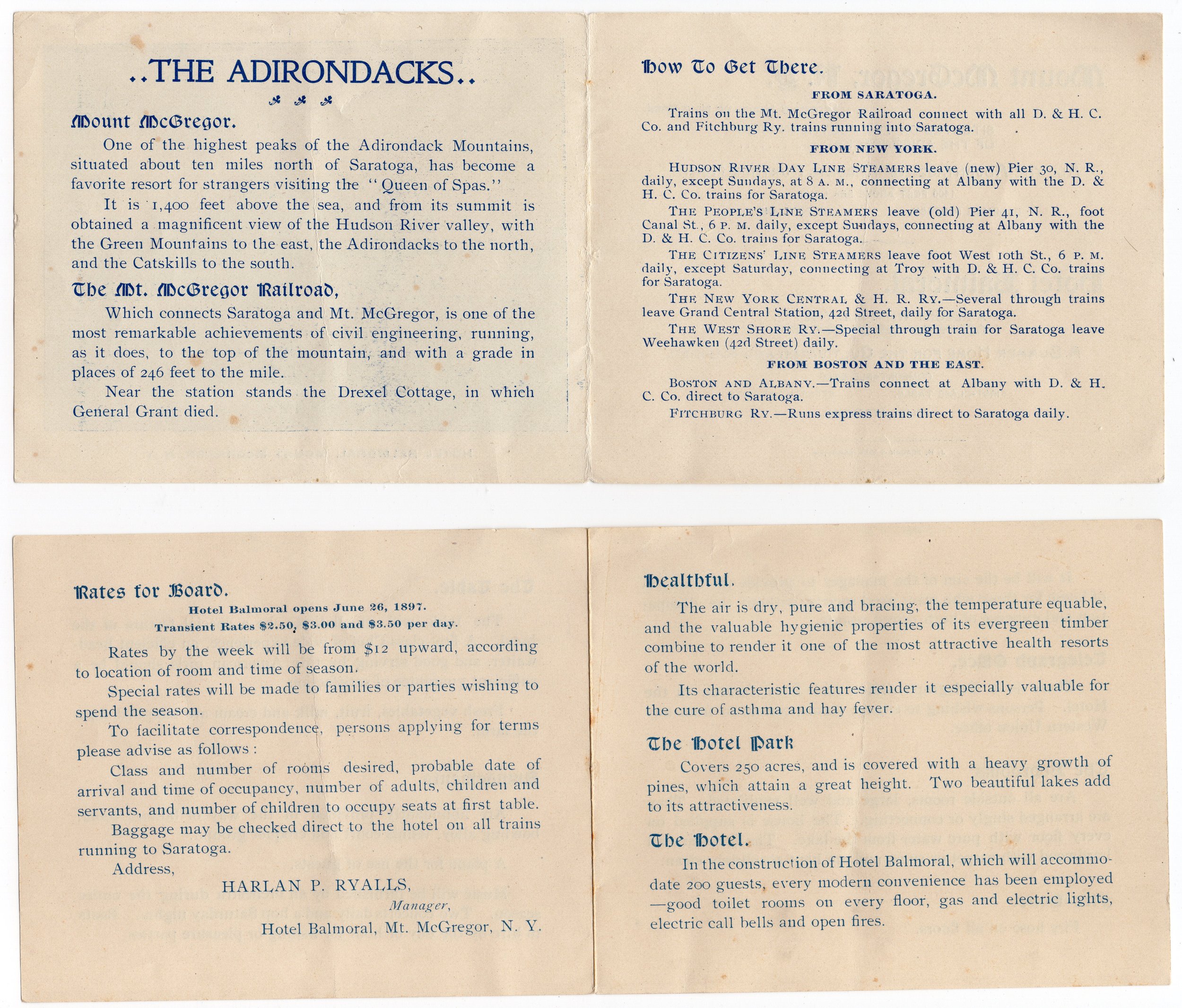

The impressive new four-story half-hexagon structure boasting 340 feet of frontage on its three faces with 22ft wide two-story porches, balconies, and 114 guest rooms was christened the Hotel Balmoral. Balmoral was a reference to the British royal estate of the same name in the Scottish Highlands, no doubt a nod to the origins of the name of the mountain itself.

As the spring of 1884 approached, final preparations were underway to open the new hotel including the firm of Green and Waterman of Troy, NY who furnished it for $15,000. The following newspaper account provides the first glimpse of the planned interior:

“The hundred sleeping rooms for guests will be provided with beds and bedding, with hardwood sets in ash and cherry. On the hardwood floor of the parlor will be placed rugs and rattan furniture with cushioned chairs. Rugs will take the place of carpets throughout the building. Andirons will be provided for thirty-seven open brick fireplaces. Chairs will also be provided for the piazza.” -The Daily Saratogian - March 27, 1884

A rare photograph of the Hotel Balmoral shows the lobby with a gaslight chandelier and a fireplace with a mantle bearing the inscription “Well Befall Hearth And Hall” which also adorned a fireplace at Balmoral Castle in Scotland. One newspaper correspondent noted that “As one looks in this hotel and sees a great open fireplace filled with blazing logs of wood, it seems to give an old-fashioned welcome to the guests not often enjoyed.”

Cabinet card photograph of the interior of the Hotel Balmoral (1880s-1890s).

Descriptions of the hotel reveal it was not simply built to make an architectural statement but also to take advantage of the surrounding conditions:

“The spacious dining-room is on the ground floor, has a northeastern outlook, and is airy and tastefully furnished. At one end, opening into it, is the principal parlor, and at the other the dining-room for nurses and children… On each floor are balconies and handsomely furnished parlors, with the same general outlook over the valley… There are no winding halls or recesses to retard the circulation of the air… the visitor at Hotel Balmoral will find a cool and refreshing air pervading the rooms and inviting to undisturbed repose.”

The Hotel Balmoral overlook deck.

The most expansive view was no longer from the overlooks or the artesian well tower but from the viewing deck atop the new hotel. To the east, visitors viewed the expansive Hudson Valley and the mountains of Vermont and New Hampshire beyond, and to the west the unbroken forest of the mountain ridge.

The grounds featured benches, seats, hammock chairs, and small pavilions for soaking in the views or natural forest surroundings (forest bathing). Recreational opportunities were expanded with a bowling alley built near the hotel as well as a skating rink and playhouse for children. A horse barn housed horses and carriages for visitors to explore the newly expanded system of drives. There were now more ways than ever before for visitors to engage with the mountain’s charms.

Benches and paths surround the Hotel Balmoral.

The Arkells developed important relationships with influential individuals in politics and business, even bringing some of them onto the board of directors. Individuals such as Titus Sheard, a Republican politician who became Speaker of the New York Assembly in 1884, became a director of the Mt McGregor Railroad that same year. James Arkell, as a newly elected member of the New York State Senate, brought his fellow senators and Lt. Governor David Hill (later governor of New York 1885-1891) to Mt. McGregor in the spring of 1884 to showcase the new Hotel Balmoral. W.J. also used his connections with publishers and purchased the Albany Evening Journal and Judge magazine in the mid-1880s. W.J. corresponded with influential national figures like Jay Gould, Cornelius Vanderbilt, and Andrew Carnegie. Some machinations to induce national political conventions with as many as 20,000 individuals to come to the mountain were put into play. Even though that plan never materialized, Mt. McGregor would host many influential politicians over the years.

Illustration of Thomas Cable from the Albany Evening Journal - June 20, 1885

Ad from The Daily Saratogian - July 9, 1884

The big day arrived on June 25th for the official opening of the Hotel Balmoral. The firm of Cable, Bailey & Co., who were instrumental in the development of Coney Island, NY, signed a three-year lease to run the new establishment. 47-year-old English-born Thomas Cable, the first manager of the Balmoral was an accomplished restauranteur and was described as “a most enterprising man.” Mt. McGregor was truly coming into its own as an established locale with telegraph and telephone service as well as a post office. Lodging rates were $3.00-$3.50 per day.

In 1884 prominent names were starting to appear on the guest list for the Hotel such as Mary Louis Booth, the editor of Harper’s Bazaar the first fashion magazine in the United States.

The Hotel Balmoral from below. (Trombley-Prosch Collection)

The electric lighting continued to be a marvel to visitors but also served as an advertisement to anyone traveling through the valley below by carriage or train. In July the electric lights were increased to 100 at the resort and the results were very noticeable:

““Mount McGregor Hotel, illuminated by the electric light, presents a beautiful spectacle in the evening. The appearance of the hotel, seen from several miles around, is almost like that of a building on fire, yet its outline is distinct.” ”

The Hotel Balmoral.

Hotel Balmoral advertisement - New York Times June 4, 1885

For many significant stories throughout history, the setting plays a pivotal role, such as in the story of the final days of Ulysses Grant. Sometimes a historical figure leaves a lasting imprint on the setting. The year 1885 would change the course of the mountain’s history forever and give it a new identity. In late April Joseph Drexel would offer the cottage near the hotel on Mt. McGregor to his friend Ulysses Grant for the summer. The Drexel family, including Joseph’s brother Anthony, were close friends of the Grant family. W.J. met with the Grants at their Manhattan home and finalized plans, assuring them that the cottage would be made ready for their summer stay. Drexel had art and decorative objects sent from his homes and arranged for furnishings from the same firm that supplied the hotel. Workmen were contracted to install carpeting, hang wallpaper, paint, and generally prepare the structure for its famous guest.

Looking up the covered walkway toward the Hotel Balmoral. ‘Welcome to Our Hero” sign for U.S. Grant’s arrival. (1885)

With the knowledge that such a distinguished guest was coming to the mountain, workmen were extra busy preparing the resort for the opening of the 1885 season. A rustic Adirondack-style covered walkway with birch posts was constructed from the train platform to the hotel grounds. The lighting system was increased to an impressive 200 lamps installed by H.H. Pollard of the Edison Electric Light Co. The walkway and hotel porches were lit with electric bulbs while the interior of the hotel featured gas light fixtures. Running water was supplied to the hotel as well as the cottages and allowed for the convenience of restrooms for guests.

Covered walkway to the Hotel Balmoral on left, Drexel (Grant) Cottage on the right.

U.S. Grant on Drexel (Grant) Cottage porch with hanging light fixtures visible. (1885)

Visitors didn’t need any encouragement to come to “General Grant’s summer home” as one paper billed Mt. McGregor. Grant was one of the most popular figures in America at that time, something not lost to W.J. who later admitted “I thought if we could get him to come to Mount McGregor, and if he should die there, it might make the place a national shrine.” The Arkells would be the closest neighbors of the Grants as the art gallery closed after a smaller exhibition during the 1884 season and was moved closer to the hotel as a private cottage for W.J. and his family. Both cottages had the luxury of electric lighting on their porches and some of their interiors until the 10:00 PM hour when the generator was switched off due to noise.

Headline from the The Morning Journal-Courier on June 17, 1885

A birds-eye view of the resort on Mt. McGregor showing the Hotel Balmoral, Drexel (Grant) and Arkell Cottages.

Grant and his valet Harrison at Mt. McGregor from The Saturday Evening Post Feb. 26, 1910

There at Grand Central Station in New York City on June 16th to personally escort the family on their journey to the mountain was W.J. and the manager of the Hotel Balmoral, Thomas Cable. The Grant family arrived on June 16th and was joined by the ever-present members of the press. The saga unfolding on Mt. McGregor in the summer of 1885 would draw international attention to the still relatively modest resort. Though time was short and he was focused on completing his memoirs, the charms of the mountain were not lost on Grant. On his first full day at the resort, the patient stole away with his valet to the overlook in front of the hotel to spy the historic valley. During many of the long hours he spent on the wide cottage porch, Grant seated himself on the northeast corner looking directly at the Hotel Balmoral. He was close enough to see the faces and hear the voices of those congregating on the scattered benches and wide piazzas of the hotel.

View from the overlook in front of the Hotel Balmoral.

Hotel Balmoral supper menu (1880s)

Although Grant spent just a brief time at the Hotel, the Grant family would make the short stroll there multiple times a day to take their meals in a private dining room. The tableware featured fine silverware provided by Louis P. Juvet, a Swiss-born jeweler and creator of the first patented mechanical globe.

The resort grounds with the Hotel Balmoral in the distance. (Saratoga Springs Public Library Collection)

The surroundings of the resort provided the Grant family with a pleasant distraction while dealing with the distress of their loved one’s suffering, especially the young children. The children’s nurse Louise brought them on walks around the grounds and to their meals at the hotel. For the Grant children, the resort was an exciting and unfamiliar wonderland. Julia, a girl of 9 at the time, later in her life recalled the powerful effect the mountain had on her:

Julia Grant and her brother Ulysses III at Grant Cottage (1885)

““We enjoyed ourselves immensely. There were rocks and big trees; a small, still, shimmering lake behind the cottage; and out in front a tiny garden, with beyond it an open space and the few trees which were grouped about the summer-house, whence was the lookout. Enough for a children’s paradise this was… These surroundings seemed mysterious, with something of fairy or goblin charm about them. I liked the sunlight coming through high oaks with their moving leaves, and I spent much leisure looking up into them as they whispered among themselves. It is the first time I remember feeling any appreciation of Nature.””

McGregor [Balmoral] Hotel showing Mrs. [Nellie Grant] Sartoris and Mrs. [Ida] Fred Grant in foreground.

U.S. Grant’s field glasses. Smithsonian

The week after he arrived a Bath Wagon was brought to the cottage for Grant’s use. In this invalid chair, Grant would make his only recorded journey to the hotel. Accompanied by his valet and doctor, Grant was wheeled up to and across the broad piazza of the hotel. He sat gazing over the valley for nearly an hour, using binoculars to explore the world far below. The distant farms could have brought daydreams of his youth in rural Ohio. Scanning the historic ground before him might have also reminded him of the bravery of his ancestors during colonial wars there. It would be his final request to be brought down to the Eastern Overlook only days before his death. Perhaps the inspiration that so many had experienced before him on the mountain, helped firm up his resolve to complete his last mission for his beloved family. Grant’s publisher and friend, Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain) would visit the mountain for a couple of days and was taken in by the Eastern Overlook stating that “...the view from that lookout… in connection with its historic associations, I consider that it presents the grandest scenery that I know of in America.”

The view from the Eastern Overlook.

Ulysses S. Grant, Savior of the Union and two-term president died at the cottage surrounded by his loving family on July 23, 1885. The death of a national hero would transform the way people looked at the mountain from that point on. The resort would continue but Grant’s name and his brave struggle became inseparable from Mount McGregor. Almost immediately Joseph Drexel made it publicly known that he intended to leave the cottage with all its contents as a memorial.

Photograph showing Drexel (Grant) Cottage and the covered walkway from the porch of the Hotel Balmoral.

A new wave of inspiration swept the mountain resort in the days following Grant’s death. Scores of visitors came to see the cottage and artists began to document the place. Artist Hugh Bolton Jones came to Mt. McGregor in 1885 to paint the final home of the American hero. He created two paintings to be given to the individuals who were most instrumental in providing a place of rest for the suffering man, W.J. Arkell, and Joseph Drexel. The resident resort photographer John Gilman was permitted to sell his photographic images to souvenir-hungry visitors of the cottage from a room on the first floor, thus promoting the location even further.

Artist Hugh Bolton Jones painting on Mt. McGregor with some female spectators. Artwork HERE

Houses, Mt. McGregor, NY by Hugh Bolton Jones (1885) Source: Heritage Auctions

The resort was not shy about using the cottage as a promotional tool. Advertising in 1886 featured the cottage prominently in both text and image. There were even short-lived plans to carve Grant’s face or name into the rock on the east face of the mountain. Drexel was accused of inviting Grant to the mountain to benefit the resort, a claim which he refuted noting the small fortune he spent out of his own funds providing for the Grant party during their stay. That same year a firm even tried to sell 1200 acres on the same ridge as Mt. McGregor, which they referred to as “Grant Mountain” that “rivals Mt. McGregor as a site for summer cottages and hotels.” There is no evidence that the enterprise succeeded but it certainly shows how eager individuals were to utilize the famous association of U.S. Grant.

Mt. McGregor Advertisement (1886)

Mt. McGregor Advertisement Booklet (1886)

“The greatest of all attractions to this elevated plateau is not its pure, bracing air, its healing pine odors and aroma, its rocky, granite formations, its forests, lakes and game, its capacious/imposing Balmoral hotel with its swings, seats, lawns and splendid, spacious surroundings... but the, attraction of the Drexel Cottage, now the property of the G.A.R., the; rooms in which General Grant lived, the chair on which he sat, the pen with, which he wrote, and the bed upon which he surrendered up his life at the call of the grim messenger death, are now and will for all future time be the grand incentive, for visiting this romantic spot.””

The guest register at the Drexel (Grant) Cottage did showcase its powerful international draw, showing “globe-trotters from England, Scotland, Sweden, Hungary, Canada, Mexico, Brazil, and Southern Africa.” It became apparent to W.J. early on that the popularity of the cottage was not going to be enough to make his mountain enterprise sustainable. Many of the visitors to the cottage did not dine or stay at the hotel. Financial trouble had begun almost immediately for the resort. Deficiencies, lawsuits, and disputes would lead to a rotating door of lessees operating the resort facilities over the next decade.

William J. Arkell illustration from The Standard Union Dec. 5, 1891

““You would hardly believe it but Grant dying at that spot has been its greatest injury as a resort. Visitors come here by thousands and approach the sacred place. They take off their hats. They begin to whisper… The guests look down and see these funereal people, hats off, going silently around as somebody was still dead in the house, and they become disconsolate and leave. So we have made a shrine at the expense of a hotel.””

Despite his conclusion that the cottage negatively affected the hotel business, W.J., along with Drexel and Kellogg, would play a significant role in preserving the structure as a shrine. Drexel attempted to transfer the cottage to the federal government unsuccessfully before his death in 1888. The following year, with the future of the cottage in doubt, the structure and contents deteriorating, and the question of funding unsettled, a plan was put in place. With members of the Civil War veterans group known as the Grand Army of the Republic and some of the financers of the resort including W.J. and Kellogg, the Mount McGregor Memorial Association was formed. It was decided to install Civil War veteran Oliver Clarke and his wife Martha as live-in caretakers of the cottage. W.J. would serve as president of the association for many years.

George G. Duy, an experienced manager of hotels in multiple states, was brought on to operate the Hotel Balmoral in 1889. Duy, with the assistance of his wife, went all out during the peak tourist season of July and August. He hosted grand events featuring the comedic sketches of humorist Marshall P. Wilder, live orchestra music, sumptuous meals, dancing, illuminations, and fireworks. These extravagant affairs served to draw visitors beyond the usual hotel guests. During this flurry of summertime activity, the Balmoral hosted the famous women’s rights advocate Susan B. Anthony who was traveling with her 24-year-old niece Maud.

One of the regular resort attractions was the live music provided by the Beacon Orchestra Club of Boston. What made the group such a novelty at that time was the fact that it was formed entirely of women. One can imagine what it must have been like to sit and gaze from the hotel porch while listening to the live orchestra music. Perhaps the perfect serenade in a perfect setting.

The Beacon Orchestra Club of Boston on the Hotel Balmoral porch.

Ad for a tennis tournament at Mt. Mcgregor (1890)

Lawn tennis was brought to America in 1872 and had developed into a popular competitive sport by the 1880s. Mount McGregor would be host to a high-stakes tennis tournament in which the grand prize was an elegant silver cup valued at $300 ($10,000 in 2023) to be presented to the winner by W.J. Arkell. There is ample evidence that W.J. thrived on competition, being heavily involved in horse racing. For those less athletically inclined, the resort offered billiards to satisfy their competitive impulses.

After nearly a decade of trying to make the resort a success, W.J.’s ambition seems to have waned and he started to entertain options to dispose of the enterprise. In 1890 German microbiologist Dr. Robert Koch was testing a potential treatment for tuberculosis. W.J. along with one of U.S. Grant’s last physicians Dr. George Shrady selected a candidate for human trials and sent him to Germany. W.J. stated at the time that he would build a treatment center at Mt. McGregor if the trials were successful. Along the same lines, W.J., in conjunction with the Commander-in-chief of the Grand Army of the Republic Gen. Russell A. Alger, supported a federal bill to turn the resort into a home for consumptive veterans. Though the trials proved disastrously unsuccessful and the veteran’s home bill was abandoned, the concept of a treatment center on the mountain would be a glimpse of things to come.

One Mt. McGregor visitor who drew some attention was Issa Tanimura the first foreign-born graduate of the Dickinson School of Law. At the time of his visit, there were only about 2000 Japanese individuals living in the U.S., over half of them in California. Tanimura toured Grant Cottage having the personal connection of his father having entertained U.S. Grant when he visited Japan in 1879. Tanimura was a gifted scholar who completed degrees at various US universities stating that his aim was to "devote his whole life toward the promotion of Japanese-American relationship."

Mt. McGregor brochure (1891)

In August of 1891 Mount McGregor would again draw the attention of the national press. W.J. arranged a 58th birthday dinner for President Benjamin Harrison at the Hotel Balmoral. W.J. had befriended and become business associates with the president’s son Russell, who had visited Mt. McGregor two years before. Nearby Saratoga Springs was in great anticipation as the Arkells and manager Albert G. Bailey prepared their hotel for the distinguished guest inviting over a hundred prominent local individuals to the birthday event. The President upon arriving at the mountain was greeted with applause at the decorated train platform. He first toured Grant Cottage appreciating the appropriate simplicity in which his former commander had died. An avid outdoorsman, Harrison pronounced the scene from the mountain summit “one of the grandest that he ever beheld.” The Balmoral dining room was decorated with flowers and a seating chart reveals those who attended including the famous cartoonist Bernard Gillam (W.J.’s brother-in-law), Vice President Levi Morton, and the president’s son Russell. The color menu entitled "A Country Dinner to President Harrison at Mount McGregor, Aug. 20, 1891" featured Harrison toasting with Uncle Sam.

James Arkell spoke first, reinforcing the indelible mark U.S. Grant left on the mountain stating that “Mount McGregor lifts its 1200 feet of granite as an eternal monument to his memory.” President Harrison echoed the sentiment stating, “This mountain has been fixed in the affectionate and reverent memory of all our people and has been glorified by the death on its summit of General U.S. Grant… It has been said that a great life went out here; but great lives, like that of General Grant, do not go out, They go on.” After the dinner, the president was a guest of the Arkell Cottage which featured electric lights, something that was only installed at the White House that same year. W.J. later pursued legal action against a newspaper that printed an accusation that his invitation to the president had the intention of personal gain.

Invitation and seating chart from President Harrison’s birthday dinner at the Hotel Balmoral in 1891

The Morning Call (San Francisco, CA) Aug. 23, 1891

Julia Grant, who was staying in Saratoga Springs that same month, made an emotional first visit back to the cottage where her husband died. Sadly, it would be only months after his visit to Mt. McGregor that President Harrison’s wife Caroline learned she had tuberculosis. Harrison brought her to the Adirondacks for her health, but she passed away in the spring of 1892. Although Saratoga Springs and Mt. McGregor never became a true summer home for presidents as some hoped, the region impressed President Harrison enough that he would later establish a vacation lodge in the Adirondacks.

Winter scene on Mt. McGregor (Crawford Collection)

Winters on Mt. McGregor were an entirely different world, they were harsh and those left on the mountain isolated. Electricity and running water were not available during the off season, adding to the struggle of everyday life. During this time William D. Green, a local farmer, was caretaker of the resort property. Mrs. Clarke, caretaker of Grant Cottage, remembered that Mr. Green “with a number of men that he employed to work in the woods, lived in a portion of the laundry -”shantying up” as Mr. Green called it.” With the railroad not in operation, Mr. Green was the only link to the valley, having a team of horses on the mountain. Mrs. Clarke remembered Mr. Green as “kindness itself and did everything he could to make life endurable under adverse circumstances.” In a world of few companions, Mrs. Clarke remembered “two faithful friends - two great, black St. Bernards that Mr. Green was keeping for Mr. Arkell. They were my attendants wherever I went.” When conditions were right, ice blocks would be cut from Artists Lake to be stored in an ice house to be used by the resort in the summer. Despite the inhospitable weather, winter offered a peacefulness and unique beauty that few were privileged to see.

Judge magazine illustration of the unexpected 1892 Democratic presidential victory depicting W.J. Arkell as a dead duck. Illustration by W.J.’s brother-in-law Bernhard Gillam. The Republican magazine would blame the Democratic victory for the economic depression of the 1890s.

1893 would mark the beginning of a significant decline for the resort. A financial panic in that year led to a four-year nationwide economic depression that touched every industry. Conditions deteriorated to the point where the Hotel Balmoral was not officially opened for the 1894 or 1895 seasons. Despite the closure, the railroad continued to bring passengers to the mountain, and Grant Cottage continued to be a popular excursion from Saratoga Springs. Grant Cottage lost the funding it was receiving from the national G.A.R. in 1893 and the New York G.A.R. Department had to take over funding. W.J. assembled the Memorial Association member to potentially establish an upkeep fund in 1896, but shortly thereafter a bill was passed by New York State Legislature to fund the cottage annually. In a sign of changing times, in September 1893 Mt. McGregor hosted what the local paper referred to as “the first excursion ever run out of Saratoga by colored people.” That gathering of 300 individuals organized by the Union Baptist Mission Sunday School occurred the same year as leading civil rights advocates such as Ida Wells and Frederick Douglass were protesting black exclusion from the Chicago World’s Fair.

The Yonkers Statesman March 20, 1895

In early 1895 the original visionary Duncan McGregor died at his home just north of the mountain in Glens Falls, NY. Despite the decline of the resort, the mountain that he had first developed continued to draw the picnic crowds just as the generous McGregor had hosted twenty years before. In August a huge group of 500 young men of the next generation, members of the Epworth League of Brooklyn, descended upon the mountain and toured the cottage. W.J.’s ambition to see the resort become a success had dwindled away and he sold his interests declaring “that the mountain as a resort was a failure.”

1897 Hotel Balmoral brochure detailing the resort amenities and amusements.

Harlan P. Ryalls the last manager of the Hotel Balmoral.

A final attempt was staged to revive the resort. 34-year-old Harlan P. Ryalls, who had previously worked as a clerk at the hotel, became manager of the resort in 1896. The resort offered free transportation to all guests of the “thoroughly renovated” Hotel Balmoral. Ryalls, who had been involved in operating a Gold Cure franchise, advertised the health benefits of the mountain. The concerted advertising efforts ultimately would not be enough to bring the resort back.

Headline from the New York Journal and Advertiser (New York, NY), Sept. 30, 1897

The Evening Times (Washington DC) Dec. 1, 1897

A bit of renewed interest in the mountain may have arisen from the highly-publicized dedication of Grant’s Tomb in New York City in April of 1897. Regardless of the level of interest, the final nails in the coffin of the once-great resort came later that year. In September a potentially deadly disaster was narrowly avoided when an engine from the railroad broke free from the mountain station. The locomotive was unoccupied but dangerously careened down the tracks at high speeds eventually derailing into a ravine in a complete wreck.

On Dec. 1, 1897, the end came in spectacularly tragic fashion. A boarder at Grant Cottage was awoken just after midnight by a bright glow coming through her bedroom windows. The Balmoral, a mainly wood structure, was engulfed in flames. Cottage caretaker Clarke raced to wake and vacate the hotel caretaker William Green out of the burning building. The fire was so extreme it could be seen for miles, lighting up the cloudy winter night. There was nothing that could be done but watch the blaze consume the ambitious dream of W.J. Arkell. When the smoke settled it was published that painters had been working in the hotel the day before and speculated that their oily rags may have caused the fire. Some sources speculated that arson, presumably for insurance fraud reasons, may have been perpetrated. W.J. ascribed to this theory stating bluntly, “I sold the place… Somebody burned the hotel, and the parties who owned it cleared $150,000.” The Grant and Arkell Cottages as well as other outbuildings survived the inferno, but the hotel and all its contents were left as an enormous pile of ash.

After some other business successes and failures in the east, W.J. moved to southern California. He fell in love with the area and would live out his days there in the sunshine. In 1927, three years before his death, W.J. wrote a book of reminiscences titled “Old Friends and Some Acquaintances” in which he briefly recalls the story of his victorian resort on Mt. McGregor. Despite viewing the endeavor as a failure overall, there was something he seemed to take pride in. As he wrote about the defining summer of 1885 he recalled that “General Grant always thought that Mount McGregor prolonged his life, and thus enabled him to finish his memoirs.” W.J. would remain with the Memorial Association and just before the new century dawned he would defend Clarke as custodian of Grant Cottage in a dispute with the New York Civil Service.

W.J. Arkell image from The New York Tribune April 4, 1897

Copy of Old Friends and Some Acquaintances autographed by W.J. Arkell and addressed to William Wrigley Jr. of the Wrigley gum company. Wrigley was a fellow southern California resident.

His Work is Crowned with Triumph illustration showing Grant’s Cottage and Grant’s Tomb from Judge (1897)

The Mechanicville Mercury May 20, 1899

Among the resort stakeholders affected by the loss were Edward A. Manice and his wife Caroline who was a prominent female golfer of her time. Insurance payouts were settled, the resort property was sold and the railroad tracks were removed from the mountain. In early 1898 there were rumors about building another hotel on Mt. Mcgregor but it never came to pass. In the spring of 1899 one newspaper declared “Mount McGregor Dead” and that “the brilliant dreams of the company of capitalists who built the [rail]road eighteen years ago have come to naught.” Another paper announced the closing of the mountain post station and declared that “The glory of Mt. McGregor as a summer resort has faded.” Despite this, visitors continued to make the journey up the mountain, again using carriages like in the early days. When a group of delegates from a Universalist convention in Saratoga Springs visited the mountain that summer, vestiges of the resort were still present, outbuildings still stood, and pathways were worn by the thousands of visitors over two decades but the field that held the mighty Hotel Balmoral was empty once again. Perhaps as those visitors stood at the brow of the hill in the “field of dreams” they wondered what the future held. They could not have known then that out of the ashes of a Victorian resort would rise a new era in the new century for Mount McGregor. U.S. Grant himself seemed to be peering into the future when he made a prediction in 1885:

““I feel the air very fine here.

This must become a great sanitorium before many years.” ”

Visitors to Mt. McGregor having a summer picnic in 1899.

Sources:

Coney Island - Luxury Hotels by Jeffrey Stanton 1997

Old Friends and Some Acquaintances by W.J. Arkell 1927

Saratoga illustrated: the visitors guide to Saratoga Springs 1884

Chinese Americans in California by Nancy Wey, Ph.D.

My Life Here and There by Julia Grant Cantacuzene 1921

The Saratoga Electric Railway by James Richmond 2022

History of Warren County edited by H. P. Smith 1885

Catering to General Grant’s Last Days by Chris Mackowski 2015

The Buffalo Commercial, March 2, 1880

The New York Times, Feb. 22, 1881, May 4, 1884, July 3, 1885, March 4, 1894

Rutland Daily Herald, Sept. 18, 1882

The Daily Graphic (New York), July 23, 1883

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Jan. 4, 1883, Aug. 4, 1889

The Glens Falls Times, Apr. 15, June 8, Oct. 18, 19, 1882, Jan. 29, May 10, Aug. 28, Oct. 16, 1883, Oct. 25, 1884

The Daily Times (Glens Falls, NY), Sept. 7, 1893

The Troy Daily Times, Oct. 23, 1883, April 23, 1884

New York Tribune, July 29, 1883, Dec. 10, 1896

The [Albany] Argus, Dec. 30, 1882, April 20, 1882, Jan. 16, 25, Feb. 2, March 29, April 18, June 6, 10, 22, July 21, 22, 24, 1883, Aug 3, 1884

The Washington County Advertiser, April 25, May 23, June 20, 27, July 18, 1883

The Plattsburgh Sentinel, June 22, 1883, Nov. 27, 1891

Utica Daily Observer, June 28, 1883

The Utica Observer, April 25, 1885

The Weekly Saratogian, May 3, 1883, May 15, 1884, May 21, 1885

The Daily Saratogian, Aug. 17, 1883, June 25, 1884

The Post-Star, June 27, July 25, Aug. 21, Oct. 24, 1883, Feb. 9, 1884, July 20, 1908

The Schuylerville Standard, July 9, 16, 1884

The Utica Weekly Herald, Sept. 23, 1884

The Lancaster Times (Lancaster, NY), June 25, 1885

The Albany Evening Journal, June 20, 1885

The Rock Island Argus, June 27, 1885

The Columbus Journal, Nov. 26, 1890

Roanoke Times, Nov. 12, 1890

Roanoke Daily Times. (Roanoke, Va), Feb. 22, 1890

The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, July 18, 1890

The World (New York), Sunday, Aug. 17, 1890

The Salt Lake Herald, Aug. 09, 1891

Rome Daily Sentinel, Nov. 20, 1891

The Helena Independent, Aug. 23, 1891

Evening Star (Washington DC) March 12, 1895

The Call, Aug. 28, 1895

Andover News, Jan. 22, 1896

The Berkshire County Eagle, Dec. 8, 1897

The Mechanicville Mercury, May 21, 1898