In Spite of Myself

By Grant Cottage Operations Manager, Ben Kemp

Inauguration of President Grant from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper - 1869

“It is men who wait to be selected, and not those who seek, from whom we may always expect the most efficient service.”

From an early age, Ulysses Grant had an awareness of politics. His father, Jesse, was involved in political discussions and debates during Grant’s childhood, even running for office and serving as Mayor of both Georgetown and Bethel, Ohio. Due to this, Grant would have had a natural aversion to political matters because of what it entailed. Contentious debating, public speaking, and self-promotional campaigning were distasteful to his reserved character. The only thing that would eventually serve to overcome his apprehensions was an overwhelming sense of duty.

Phrenology diagram

There were those that later claimed to have seen a great potential in him during his younger years. They claimed to have recognized in him a reserve of faculties that would someday come to serve his country well. One rather whimsical tale takes place when Ulysses was 10 years of age and a traveling Phrenologist came to his boyhood town of Georgetown, Ohio. It was at the height of the popularity of the pseudoscience that claimed to gain valuable insight based on the shape of an individuals’ head. According to accounts during a public demonstration, Ulysses was summoned by the doctor for a reading. After examining the boy’s skull, the doctor remarked “It is no common head! It is an extraordinary head! It would not be strange if we should see him President of the United States.” Of course, Ulysses would later be singled out from many others that likely received the same prognosis.

As a young Cadet, Grant would win his first election at West Point Military Academy when he was made President of the Dialectic Society. Literary discussion and debate was something Grant had some experience with at school when he was younger so either his abilities were recognized or he was simply willing to fulfill the role.

Grant would stay out of presidential politics for the next two decades while in the military. He would cast his first presidential ballot for Democrat James Buchanan as a 34-year-old civilian in 1856. He pointed out later that his motivation was the preservation of the Union, as he had heard rumors of secession already and feared a Republican victory might lead to dissolution. His vote would come back to haunt him in the form of a political cartoon and he was said to have joked that his “first attempt in politics had been a great failure.”

“Grant’s First and Last Vote” from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper 1872

After having impressed his mother-in-law, Ellen Dent, with his intelligent discourse in political discussions with her husband she remarked to her daughters, including Julia "My daughters, listen to me. I want to make a prophecy ... remember what I say… that little man will fill the highest place in this government. His light is now hid under a bushel, but circumstances will occur, and at no distant day, when his worth and wisdom will be shown and appreciated. He is a philosopher. He is a great statesman."

Julia would share her mother’s view and always had a deep abiding faith in her husband that bordered on the mystical. During a difficult period on the farm in St. Louis she supposedly told gathered family members of a dream she had. She claimed that in her dream her husband was elected president and then stated confidently, “we will not always be in this condition,” and using one of her pet names for him “Wait until Dudy becomes president." Of course, this was laughed off by those present, but Julia continued to harbor great aspirations for her husband, even if he did not have them for himself.

In 1859 Grant would have his first taste of politics when he applied for the position of county engineer. Despite a good number of endorsements, he lost the vote. One of the reasons for the loss was thought to have been his association with his in-laws, the pro-Democratic and pro-slavery Dent family, when three of the five Board Commissioners were Free-Soil Republicans. Supposedly there was some bitterness stemming from the feeling of being unfairly judged. It certainly did nothing to give Grant an appetite for politics. Although keenly aware of the volatile political debate and momentousness of the 1860 presidential election, Grant, having recently moved to Galena, Illinois, was ineligible to vote.

Politician Elihu Washburne

As soon as the war began, Grant watched as others scrambled for military commissions through “political wire-pulling” and refused to engage in it. Despite trying to distance himself from politics, during the war General Grant’s name was put forward as a possible candidate for President against Lincoln for the 1864 election. He did everything he could to convince others he was “not in the field” stating “nothing…would pain me so much as to see my name used in connection with a political office.” He wrote to Isaac Morris, “You say I have the power to be the next President. This is the last thing in the world I desire.” “I am not a politician, never was and hope never to be.” To his father, he wrote, “Nothing personal could ever induce me to accept a political office.” He even joked the notion off by saying maybe he would run for Mayor of Galena, Illinois so that he could build a proper sidewalk to his house (Galena built him a sidewalk anyway). The General made it abundantly clear his only objective was to remain in the service to fulfill his duty and “see this rebellion suppressed.” Above all, Grant certainly did not want to run against Lincoln and as Congressman Eben Newton of Ohio warned him “permit ourselves to be divided up into factions… weaken[ing] our power to accomplish the object we are striving for.” All of this did not serve to stop some from harboring confidence in Grant’s future prospects, like Congressmen Elihu Washburne from Galena. Washburne, Grant’s promoter and defender in Washington during the war, stated: "after old Abe is through with his next four years, we will put him in."

Some cautioned Grant not to get involved in politics, like his friend General William T. Sherman. Upon receiving the Republican nomination in early 1868, Grant acknowledged it was due to “the feelings of the great mass of those who sustained the country through its recent trials.” And simply “I endorse their resolutions.” He ended his acceptance letter with a line that would become his emblematic campaign slogan “Let us have peace.” Grant explained to Sherman the situation which prodded his sense of duty “I have been forced into it in spite of myself. I could not back down… leaving the contest for power over the next four years between mere trading politicians, the elevation of whom, no matter which party won, would lose to us largely, the results of the costly war we have gone through.” Sherman, whatever his misgivings about politics, had to admit to his friend that he thought he would govern fairly writing, “I have abstained from all politics because… I have had a deep seated aversion to them from old experience… and… [am] averse to putting faith in mere political men. To all who apply to me, I say you will be elected, and ought to be elected, and that I would rather trust to your being just & fair…” Sherman added a further warning to his friend, “All men when clothed with power will use it, and sometimes abuse it.”

The Presidential Mansion (White House) in the mid-19th century.

There were practical reasons why Grant would not seek the highest office of the land. Knowing his respected friend, Lincoln, was gunned down due to his office would make anyone think twice about the safety of the position for himself and his family. The salary was better as president, but not perpetual as in the military, without a presidential pension he would be left trying to earn an income after his term(s). Grant held out through the instability and divisiveness of the Johnson administration and his impeachment and near removal. He endured a distinct fear of a coup involving a new “southern congress.” All of this coupled with being uninitiated in the world of often corrupt Washington politics made the General naturally apprehensive. He shared the sentiment that “If this were simply a matter of personal preference and satisfaction I would not wish to be President…To go into the presidency opens altogether a new field to me, in which there is to be a new strife to which I am not trained.” None of this would be enough to stop him though if he felt duty-bound. General Philip Sheridan recognized the situation stating “I believe you are sacrificing personal interest to give our country a civil victory.”

1868 Campaign flag on display at the Old Market House in Galena, IL.

Grant would not campaign on his own behalf but, after a two-week tour of the west, waited out the rest of the summer and fall of 1868 at his Galena home. To those who were present at Congressman Washburne’s home on the November night of the election, Grant was described as perfectly calm as the results came in by special telegraph wire. At two o'clock in the morning, victory was declared and Grant walked home and told Julia simply "I am afraid I am elected.” Grant would feel the immediate effects of his victory, fielding relentless requests from office-seekers over the next few months.

The parlor of Washburne’s Galena home where U.S. Grant received news of his election in 1868.

When Grant stood in front of the inaugural crowd on the damp and cold afternoon of March 4, 1869, he told the listeners that he was not there for his own interests, but for those of his country. “I have taken this oath without mental reservation and with the determination to do to the best of my ability all that is required of me. The responsibilities of the position I feel, but accept them without fear. The office has come to me unsought; I commence its duties untrammeled. I bring to it a conscious desire and determination to fill it to the best of my ability to the satisfaction of the people.”

President Grant’s first Inaugural Address 1869

In the final months of his life, struggling against throat cancer, Grant would put a simple sentiment into his memoirs that would define his career. “It is men who wait to be selected, and not those who seek, from whom we may always expect the most efficient service.” He believed those with pure intentions and driven by a sense of duty were not as likely to seek office for themselves but wait to be requested. Other than simply offering his services to the U.S. Army when the Civil War broke out, Grant never sought promotion or campaigned for office on his own behalf. He let his actions stand for themselves to be judged worthy of promotion or not.

Grant, at 46 was the youngest president up to that time.

While pondering his life in his final weeks Grant would write to his doctor "It seems that one man's destiny in this world is quite as much a mystery as it is likely to be in the next… I certainly never had either ambition or taste for political life, yet I was twice president of the United States." He would echo this modest outlook in the beginning lines of his memoirs stating, “Man proposes and God disposes, there are but few important events in the affairs of men brought about by their own choice.” In his perspective of destiny, he left out a crucial element of motivation, duty. Duty is what drove him to dash down the bullet-ridden streets of Monterrey Mexico, to nurse the dying on the Isthmus of Panama, to endure lonely western outposts, to push through illness to maintain a St. Louis farm, to fight a horrific war to preserve his country, to take on the reputation destroying battleground of politics and finally to will himself to live long enough to pen his memoirs for the sake of his beloved family. More than anything it was that same overriding sense of duty that placed a humble American on the portico of the Capitol on that rainy March afternoon, pledging to faithfully serve the will of those who had put him there to the best of his ability. In the 150 years since that day Ulysses Grant’s presidency has been the subject of intense criticism. However, if one is willing to look a bit deeper, they will discover the underrepresented achievements of the man who became president in spite of himself.

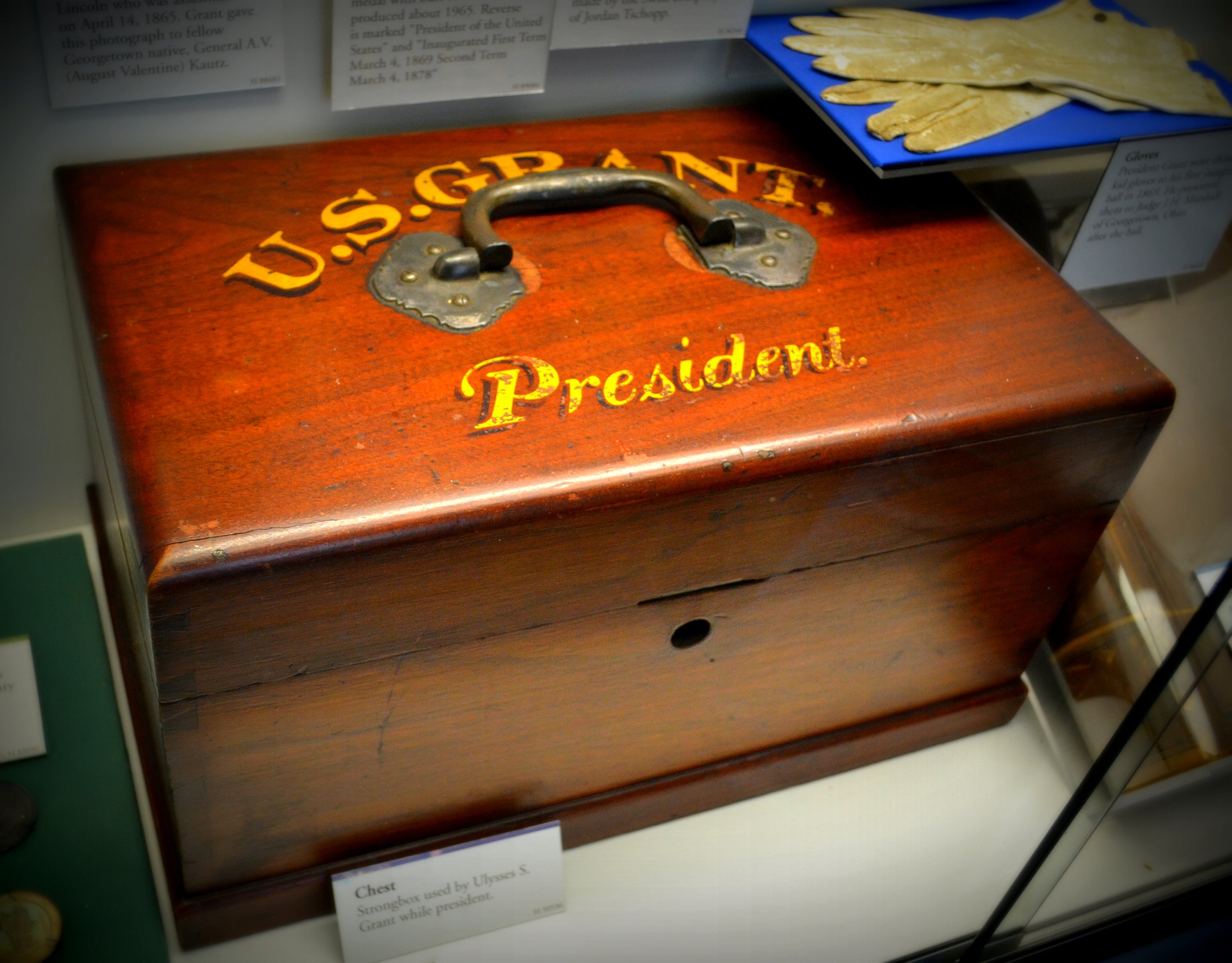

President Grant’s strongbox on display at the U.S. Grant Birthplace in Pt. Pleasant, OH.

Sources:

PUSG Letter to Barnabus Burns 12/17/1863

PUSG Letter to Isaac N. Morris 1/20/1864

PUSG Letter from Eben Newton 2/11/1864

PUSG Letter to Joseph R. Hawley 5/29/1868

PUSG Letter from Gen. Sherman 9/28/1868

PUSG 1st Inaugural Address March 4, 1869

Grant Takes Command by Bruce Catton

The Personal Memoirs of Julia Dent Grant

The General’s Wife by Ishbel Ross

Grant by Ron Chernow

American Ulysses by Ron White

Grant’s Final Victory by Charles Flood

Captain Sam Grant by Lloyd Lewis

Grant by Jean E. Smith

Let Us Have Peace by Brooks Simpson