By Ben Kemp (Grant Cottage Operations Mgr.)

1885 Newspaper Ad

Lulu’s doll from Appomattox Source

Mrs. Grant’s 1865 Souvenir Jewelry Set Source

The urge to remember ones’ experiences through collecting objects is an age-old one. Souvenirs were sought after in the ancient Roman empire and by travelers visiting holy sites throughout the middle ages. It has gone by many different names; relic hunting, souvenir seeking, memento gathering, treasure hunting. The practice ranges from the relatively innocuous gathering of natural materials like flowers to the outright theft of precious and valuable items. In Victorian-era American society the practice was prevalent enough to concern those who oversaw sites of historic significance including Grant Cottage.

Souvenirs were collected by citizens and soldiers throughout the American Civil War. General Grant received various mementos from admirers including items such as Italian General Garibaldi’s dagger in the summer of 1864. Some events naturally drew much more attention in this regard. On April 9, 1865 the two opposing commanders Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee met in the home of Wilmer McClean in Appomattox Court House, VA. Lee formally surrendered his army, an act recognized by witnesses as a pivotal moment of history. Those present began to buy, trade and steal to acquire objects from the home as mementos of the historic occasion. Even McLean’s 7-year old daughter Lula fell victim to the souvenir hunters as a Union officer walked off with her rag doll. Mrs. Grant was not left out either when lager that year she received a finely carved jewelry set made from an apple tree where General Lee had met Union officers just before the surrender.

1868 Presidential Campaign Token

As Grant’s fame continued to rise after the Civil War he received many souvenirs and many were requested of him. Political campaign objects from Grant’s two terms became especially treasured souvenirs for many Americans. Not a hunter himself, in 1872 President Grant received a deer head wall mount from a Mr. Gussenhoven from the Wyoming Territory, a place Grant had visited a few years before. Like some souvenir gifts there was a motive as the item came with a request for an appointment at the new Yellowstone National Park, something that the President was unable to offer as no such positions had been created yet.

Roman mug and pitcher set from Grant’s World Tour (1877) in Smithsonian Collection.

A souvenir Japanese fan from Grant’s world tour on display at Grant Cottage.

An ornate presentation sword from Grant’s collection now at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History

Perhaps the period of Grant’s life where he obtained the largest number of souvenirs was his world tour from 1877-1879. From the many regions he visited he collected a wide array of items of various value. His grandson Ulysses III remembered that as a young boy his grandfather had shown him the many items in his collection, each carrying its own unique tale. Many of these items would not be passed down to relatives but instead a good portion would be turned over to William Vanderbilt to whom Grant was indebted after a financial scandal in 1884. In January 1885 famous showman P.T. Barnum contacted Grant about acquiring and showing many of Grant’s collection, only to be disappointed they had already been transferred. Barnum knew a fortune could be made simply by charging people to see the items. Vanderbilt would himself eventually turn over the relics to the Smithsonian Institute in Washington DC.

The act of memorializing an event with a physical object in and of itself is not a criminal or inappropriate practice. The methods used, intentions and the nature of the items obtained are what can turn an otherwise innocent practice into a breach of conduct, even criminal perhaps. Human nature is to be occasionally overwhelmed by the gravity of a situation and when this happens passions tend to outweigh reasonable protocol. With photography still being relegated to professionals in the 1880’s it comes as no surprise that there would be relic hunters on Mt. McGregor following Grant’s death. Following a highly-publicized illness of such a famous figure and the place of death being an easily accessible public place created a veritable souvenir frenzy. Many were respectful, taking a mountain flower or leaf, while some were driven to more destructive and criminal acts, indicated by incidents well documented in the papers at the time of Grant’s death and funeral.

“So strongly has the death of the old General taken hold upon the popular heart that scarcely any of the people who come here for the day, go away without plucking a sprig of fern, or blooming wild flowers which grow near the place that the General used to take when walking, or riding in his invalid carriage, and stowing it carefully away in a book or a paper as if it were of priceless value.”

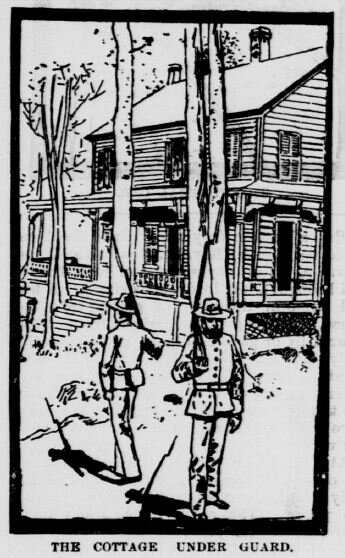

Early on the threat was well understood so in the days immediately after Grant’s death Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R.) veterans and regular army soldiers arrived to guard the Cottage and surrounding property. As the public filed through the parlor to pay respects to the hero lying in repose “the guard of honor of the U.S. Grant Post of the G.A.R. of Brooklyn kept strict watch and ward. They bad been instructed to prevent any vandalism by relic hunters, and they were dispersed about the room so as to watch the crowd without impeding its movements.” Even with the presence of the guards, acts of bold relic hunting vandalism continued. After the first day of public viewings the undertaker noticed that one of the screws from Grant’s casket had been removed and was “utterly at a loss to explain how this theft could have taken place, because the casket had been very closely watched.” The report went on to state that, “This one incident is enough to show the great care that is necessary in guarding the Drexel cottage and everything relating to it.”

The Cottage under guard at night.

Although the practice was condemned by most to some it was “regarded as a very proper sort of hero-worship, not as theft.” The desire was so insatiable that the “relic hunters make almost super-human efforts to get within reach of the cottage to get even a splinter of the porch on which the General passed his time.” After a frighteningly dangerous lightning strike that traveled into the children’s room of the cottage it was reportedly “discovered that a piece of the lightning rod that was placed on the cottage had been broken away and carried off… which it is surprising did not lead to more serious consequences.” The thefts did not respect persons either as Grant’s main physician Dr. Douglas reportedly discovered personal handwritten notes from his patient missing from his coat pocket and “sustained what to him is an irreparable loss, and it is indirectly attributable to this inordinate desire for relics.”

Other structures on the mountain property were not safe either, as the following report regarding the rustic covered walkway from the train station to the Hotel Balmoral illustrates:

G.A.R. guards with visitors on Mt. McGregor.

“The relic hunter is here with his usual rapacity. There is nothing too sacred and apparently nothing too common if it has the remotest connection with the life and death of General Grant on this mountain to prevent him putting his sacrilegious hands upon, and, if possible, carrying it away by stealth. The colonnade in front of the cottage has long been a favorite place for the incursion of persons with tastes of this objectionable character. This colonnade is constructed of silver birch, and the marks of knives used for the cutting away of the bark are to be seen on every pole.”

As preparations began to remove the General’s remains from the mountain, the funeral train was decorated. As pieces of discarded decorative cloth hit the ground eager visitors snatched up every last bit, but it didn’t end there. Even though a “military' guard was placed over it and a sentinel walked alongside of it day and night. This precaution did not prevent the relic hunter from carrying on his nefarious work, and…it was found that it had been cut in several places.” In fact, they had even reportedly cut a section of the car itself off prompting the drastic action of removing the train from the mountain and storing it under lock and key in nearby Saratoga Springs.

The decorated funeral train descending the mountain.

These bold actions were matched by the similarly determined efforts to purchase souvenirs. There was reportedly “hundreds of applications” to purchase furniture and other items from the Cottage and some offers for the entire structure. An offer of $85,000 was reportedly made for the Cottage but would result it in being deconstructed and sold as souvenirs. To the owner Joseph Drexel selling the Cottage was out of the question, the only appropriate use in his mind was that of a fully intact and furnished memorial to the illustrious American. As the interest in Grant’s life and career hit a fever-pitch immediately after his death, other Grant-related sites began to encounter relic hunters and offers to purchase the structures. Some of these offers no doubt would have included the buyer “making the most” of the purchase by disassembling the buildings and selling them piece-meal. Grant’s birthplace and his City Point headquarters cabin were both moved and placed on display in cities for a time. At Mt. McGregor the press reported that it was Drexel’s intention “to leave a strong guard at the cottage after the departure of the funeral train, or the building will be carried off in pieces.”

The souvenir craze only increased in scope as Grant’s body traveled by train to Albany and on to New York City. Workshops and workmen creating materials for the funeral became the focus of crowds of curious spectators and there were numerous requests to purchase the items after use. Offers in the thousands of dollars were made to acquire Grant’s funeral car and catafalque. Decorated vehicles and structures associated with the funeral fell victim to relic hunters and had to be guarded. Pieces of the floral arrangements at City Hall in New York were taken by the masses that poured past the General lying in state. At the temporary tomb site in Riverside Park police were busy “preventing relic hunters from carrying off not only all the pebbles that were excavated from the site of the tomb but all the bricks that are to be used in the walls.”

As masses of the public, dignitaries and soldiers poured into New York City for the Aug. 8th funeral, on the streets were many dealers hawking hastily prepared souvenirs. Mourning and memorial souvenirs came in all shapes and sizes including paper programs, medals and mourning ribbons. A competing souvenir at the time were miniature versions of the Statue of Liberty being sold to raise funds for the pedestal of the future monument (a cause Grant had supported). Nothing was too small as even a shell casing from the salute volley fired by the 22nd National Guard Regiment at Grant’s funeral was engraved and kept as a keepsake. The undertaker who helped organize the New York City funeral, Stephen Merritt, was inundated with requests for mementos, generally he resisted but was willing to give some items to military units and veterans that had participated.

Shell casing from volley fired at Grant’s New York City funeral on August 8th, 1885. Source

Guards at the temporary tomb.

After the funeral guards were posted at the tomb but still vandalism continued with “some sacrilegious visitors… knocking pieces off the bricks on the corners of the vault as mementoes and in defacing it by writing their names upon the brick work with pencils.” As nighttime was the main concern, the tomb received electric lighting to discourage “desecration at the bend of sacrilegious relic hunters.” Even a nearby solitary 18th century grave of a five-year old “amiable child” was not off limits to the “Relic Fiends” so it too required a guard.

Precautions were even necessary in 1897 when examining and transferring Grant’s remains to the sarcophagus in the newly completed tomb. Fences had to go up and work done quickly to disassemble and remove the components of the old brick tomb. The Mayor of New York at the time, William Strong, after receiving numerous requests from G.A.R. Posts throughout the country, secured 1000 of the estimated 11,000 bricks from the temporary tomb to distribute to the veterans posts.

Souvenir brick from Grant’s temporary tomb with Mayor Strong’s signature. Source

Back on Mt. McGregor an incident occurred in the fall of 1885 that would prove that relic hunters were going to be a long-term issue:

“On Friday afternoon after a party of visitors who had been admitted to the cottage had left, the pencil with which General Grant had written his last brief messages was missing, having evidently been picked up as a valuable souvenir. The passengers by the train had not left when Conductor Frost was notified of the robbery. With the discernment that would have done credit to a detective of experience he fastened upon a gentleman of very respectable dress and appearance as the robber and questioned him so sharply that ho presently took Frost aside and restored the stolen property. Mr. W. J. Arkell yesterday removed the tablets and pencil and handed them to Mr. J. W. Drexel to be put in a separate case. This act of vandalism will make it much more difficult for visitors to Mount McGregor to get into the cottage until all the portable objects there are placed beyond the reach of pilferers.”

Sunrise at “Grant’s Last View” monument at the Eastern Overlook.

The case on the wall in the Cottage containing the pencil and tablets is a reminder to visitors even today of the relic hunting of the past. Another visible reminder is the fence placed around the Eastern Overlook monument to “Grant’s Last View” where visitors had chipped away previous stones.

About a year after Grant’s death, in 1886, the resort photographer at Mt. McGregor, John Gilman, was permitted to operate a photo gift shop out of a room in the cottage:

“All visitors are invited to an adjoining room, where photographs of the Grant family as a group, single pictures of the interior and exterior of the cottage, small albums of compressed flowers collected on the mountains, with the common and botanical names, are all sold, and the money thus obtained is used to defray the expenses of taking care of the cottage.”

One of a series of cabinet card photos sold in Mr. Gilman’s souvenir shop at Grant Cottage.

Preserved flower from “Wildflowers of Mount McGregor” souvenir booklet.

The sale of mementos, more than just making some revenue to care for the Cottage, helped satiate the desire for illegal souvenirs thus saving many of the items still on view in the Cottage today. Manufactured souvenirs remain a multi-billion dollar segment of the tourism industry today. Souvenirs of the distant past still surface on modern auction sites, things as intimate as strands of Grant’s hair taken by the undertaker and flowers from the arrangements at Grant Cottage. Some of these items find their way back to where they originated like Lulu’s rag doll from Appomattox that eventually made it back to the National Park 128 years later. All of Grant’s belongings were not lost in the financial scandal either and many Grant descendants have treasured keepsakes in their private collections. There are now numerous Grant-related sites, including the most recent The Ulysses S. Grant Presidential Library & Museum that house many items and continue to accept more for all to see.

A souvenir memorial album containing images of Grant’s life.

With the enduring popularity of the Cottage as a destination established by the tens of thousands of visitors by 1887 the concern was still apparent. Those in charge had “their eyes and hands full… to hold in check the thieving propensities of the relic-hunters.” In 1889 live-in caretakers became the first line of defense for the cottage with the press reporting that, “It is necessary to have a custodian constantly there to prevent vandalism, otherwise the relic hunters would carry off the whole house in small pieces. Mr. Clarke will… take up his residence in… the cottage and devote his entire time and attention to its care.” With it being difficult to retrieve part of the structure or its contents visitors simply took the mountain itself: “many pick up the gravel of the walk around the house, supposing that they are carrying off stones trodden by the foot of Grant. The truth is that this gravel has to be renewed every month on account of these relic hunters, and the stones they carry away have never seen Grant.” Despite the decline of the mountain resort into the 1890’s the concern still remained that if the Cottage was ever left unattended, "There are so few things in the cottage that if any were taken away or chiseled there would be nothing left in six months." Fortunately, due to the dedicated watchful eye of the many individuals that have helped caretake the cottage over the last 130 years, the past has not been carried away.

A final note on treasure hunting:

In modern times casual visitors are encouraged to purchase souvenirs and take digital images at historic sites so that all the important materials can remain for all to appreciate. There are still those individuals that get carried away and remove things from the site they shouldn’t whether they are a seasoned metal-detectorist or a casual visitor finding an object on the ground. To discourage this activity there are laws prohibiting the removal of any objects from State Lands in New York because if objects are taken by non-professionals important shared history resources are lost for all. If you find something at a Historic Site you believe may be archaeologically significant, please don’t get carried away and pocket it, but instead do the right thing and report it to site staff. The reason we have the historical treasures we have today is due to those millions that came before us that were able to admire things without taking them.

More info can be found on the New York Archaeology website.

Sources:

At The Tomb - The Weekly Auburnian 8/14/1885

The Contemptible Thief - Paterson Daily Guardian 9/21/1885

Relic Fiends - NY Herald 8/10/1885

Where Grant Breathed His Last - The Warren Republican 9/9/1887

Relic Hunters - The Philadelphia Enquirer 8/3/1885

Scenes at Mt. McGregor – The New York Tribune 7/27/1885

Old Tomb Torn-Down - The Albany Morning Express 4/28/1897

Gen. Grant’s Remains - The Glens Falls Times 5/10/1897

Guarding The funeral Train -The Evening Star 8/5/1885

The Day’s Events at Mount McGregor - The Yonkers Statesman 8/1/1885

Why a Guard is Needed - The World 7/30/1885

Grant’s Galena Home - The Evening Telegram 7/29/1885

Statue of Liberty Enlightening the World (Ad) - The Evening Capitol 7/23/1885

Scenes at the City Hall - The Evening Post 8/10/1885

Grant Bricks for G.A.R. – The Topeka State Journal 5/5/1897

Work on the Temporary Tomb at Riverside Park - The Philadelphia Enquirer 8/3/1885

The Hunt For Relics: Playing Havoc With Grant’s Tomb - New Haven Daily Morning Journal & Courier 8/12/1885

Where Gen. Grant Died - Commercial Advertiser 11/12/1890

The Car Taken to Pieces - The World 8/11/1885

The Shrine of Mount McGregor - The Buffalo Courier 8/4/1890

The Richfield Springs Mercury 10/24/1889

The Salt Lake Herald 8/5/1894

Seneca County News 7/12/1887

The Evening Telegram 7/31/1885

The Captain Departs – By Thomas Pitkin 1973

The Papers of U.S. Grant

Some of General Grant’s World Tour Souvenirs.